Like many students across Illinois, Phillip Hartsfield is about to complete his undergraduate degree in the midst of a global pandemic. And like many other students, Hartsfield, who has concentrated in the fields of law, psychology, and sociology, learned how to complete his classwork under less than optimal conditions in 2020. He has written analytical essays on challenging texts, delivered a twenty-minute capstone presentation despite not having consistent access to a library, and persevered even though he has had an uneasy relationship with institutional policies and administrators.

But unlike most students, who’ve adapted to instruction via Zoom classes and are preparing to graduate through virtual commencement ceremonies, Hartsfield, thirty-six, has not had the luxury of participating in synchronous class discussions. He won’t be able to celebrate his graduation with his family or friends.

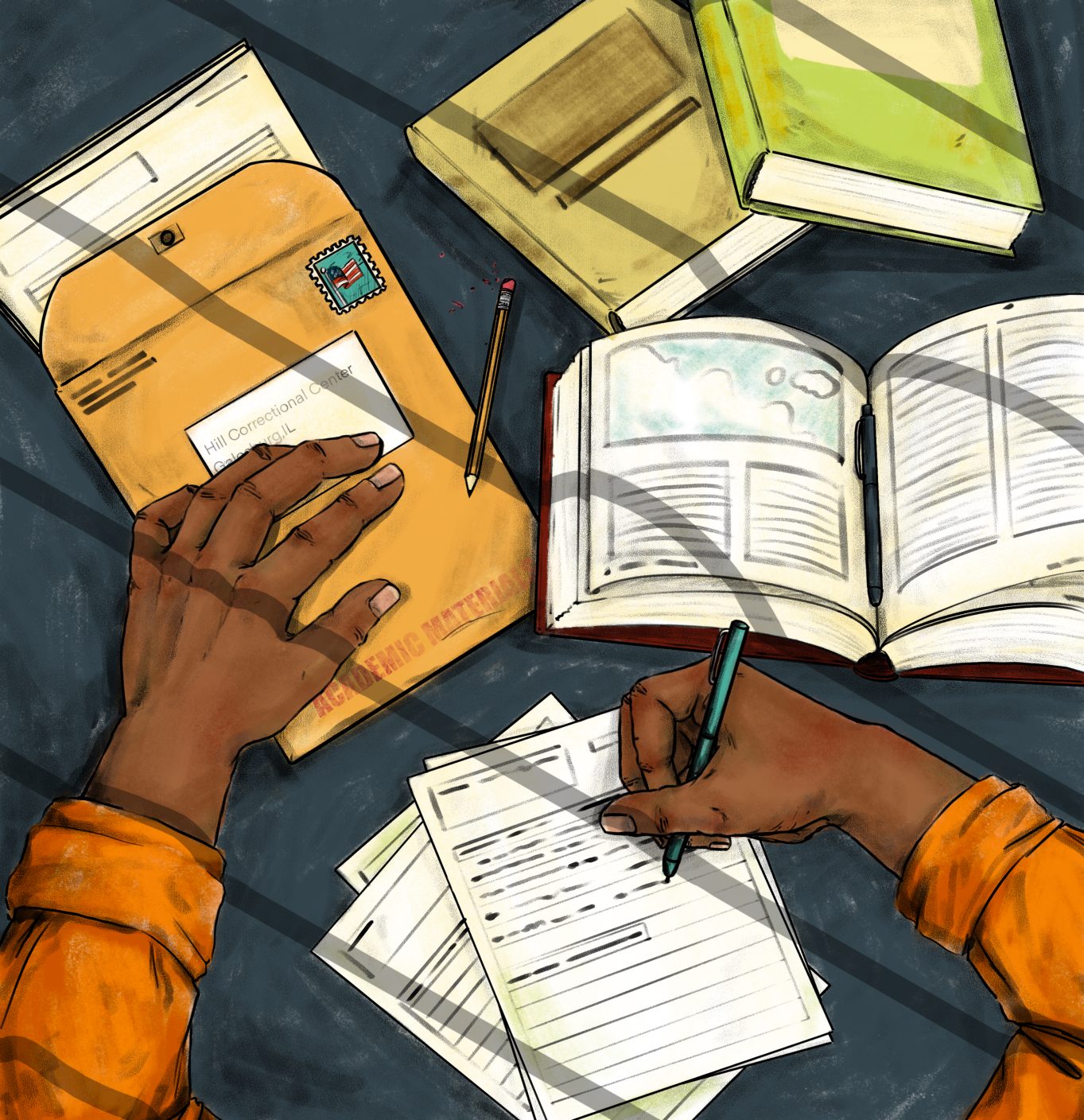

That’s because Hartsfield is currently incarcerated at Hill Correctional Center in Galesburg, Illinois. As a student enrolled in the Prison and Neighborhood Arts/Education Project, he’s one of hundreds of people partaking in a higher education program while incarcerated in Illinois state prisons.

Prior to the pandemic, incarcerated Illinoisans already faced a multitude of challenges in pursuing higher education in prison (HEP). But as with so many other aspects of society, the coronavirus has exacerbated those challenges. Whereas in the past incarcerated people may have wrestled with writing papers without access to a desk, they now may be struggling through schoolwork while confronting the additional tragedy of witnessing fellow prisoners die of COVID-19.

There are currently nine HEP programs at seven Illinois Department of Corrections (IDOC) facilities across the state, according to the Illinois Coalition for Higher Ed in Prison (IL-CHEP). Of those nine programs, four take place at Stateville Correctional Center, a prison roughly an hour’s drive southwest of Chicago. Two programs serve Danville Correctional Center, located two-and-a-half hours south of Chicago.

Those two prisons are really the outliers when it comes to HEP programs, according to Katrina Burlet, a member of IL-CHEP and advocate for incarcerated people. Other IDOC facilities have one or zero HEP programs. The reason for that? “It is literally one hundred percent a proximity thing,” Burlet said. Stateville is located close enough to Chicago for college instructors to visit. Danville Correctional Center is right next to the town’s community college, and not far from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC).

The coronavirus crisis has prompted educators with HEP programs to adapt their programming as well. Many educators have elected to continue their classes in correspondence format. Others have declined to teach by correspondence and instead are pursuing different educational initiatives to support their students. Some educators are creating packets containing re-entry resources and others are utilizing more tech-based solutions in the hopes of crafting a richer educational experience for students.

Burlet said that although Stateville has a robust slate of HEP programming, it still only has classes available for a small fraction of the population. “It’s definitely the best facility with the most opportunities and it’s still an absolute failure, if we’re taking honest consideration of how it’s actually doing,” she said.

Burlet coached a debate team at Stateville until 2018, when the debate program was suspended after participants held a debate on the topic of parole in front of state legislators and media, and Burlet was banned from entering IDOC facilities. (Burlet, with the help of the Uptown People’s Law Center, is suing IDOC in the hopes of getting the program reinstated.)

Besides the established programs at Stateville and Danville, there are two “up-and-coming” programs of note, according to Burlet. Two relatively young HEP programs have sprung up at Sheridan Correctional Center and East Moline Correctional Center, thanks to the efforts of instructors at Benedictine University and Augustana College, respectively. Benedictine intentionally set up its program at Sheridan rather than Stateville, which it is closer to, to take advantage of an “opportunity to bring college programming to a prison that didn’t have it already,” according to Chez Rumpf, an HEP instructor and assistant professor who teaches sociology and criminal justice.

In the early days of the pandemic, members of IL-CHEP “really scrambled to think not about education, but just about life-saving stuff,” said Sarah Ross, a co-director of the Prison and Neighborhood Arts/Education Project (PNAP) and assistant professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. The situation was dire: social distancing, one of the most important ways of preventing the spread of the coronavirus, is impossible in prisons. Not coincidentally, Stateville was an early epicenter of a COVID-19 outbreak.

In March, IL-CHEP delivered a letter to Governor J.B. Pritzker calling on him to take measures to decarcerate IDOC facilities and protect public health. In April, the coalition started working to get hand sanitizer into IDOC prisons. From June to August, the group participated in a six-week “Summer of Action” initiative where they called for, among other things, the shutting down of Vienna Correctional Center in southern Illinois. Towards the end of May, Ross was able to return to co-teaching a PNAP class on visual art.

Founded in 2012, PNAP is one of the oldest of the HEP programs at Stateville. (In the 1970s, nearby Lewis University ran a degree-granting program for incarcerated people in Stateville.) PNAP usually runs about fifteen classes per year on a semester schedule, with fifteen students enrolled in each class. The classes are not for-credit, but students can use their participation in PNAP classes towards certain degree-granting programs that accept them, such as Northeastern Illinois University’s (NEIU) University Without Walls program.

Because visitations to IDOC facilities have been suspended since March 14 of last year, Ross, her co-instructor Aaron Hughes, and other PNAP instructors have been teaching their classes via correspondence. Twice a month, PNAP dropped off packets containing course materials and assignments for their students at Stateville.

Although Ross couldn’t hold classes in person, she was intentional about fostering a sense of community with her students. In each packet, she included a sheet intended to facilitate communication between the class instructors and the students. The sheets included dispatches from Ross and her co-instructor—“so that we’re not a machine just sending in assignments”—and inquiries about how the students were doing as human beings outside of class.

Normally, in a PNAP art class, Ross would demonstrate techniques side-by-side with her students. Now, she has to carefully detail her thought processes step-by-step on paper. Ross has had to develop other workarounds, too. During in-person class discussions, Ross would be able to project images of murals onto the wall; now, she and her students must make do with murals being printed on 17” x 11” sheets of paper. Before the pandemic, Ross and her fellow instructors would be allowed access to the cell house to check on their students if they weren’t showing up to in-person seminars. Now, if a student stops sending in assignments, there’s less that instructors can do to check on them.

There are also logistical challenges with course packet drop-offs and pick-ups at the prison. “I usually get half of the [assignments] back on the date that we ask them, and then the next week, things trickle in,” Ross told the Weekly in a Zoom call as she put together course packets.

“There’s a lot of room for glitches,” said Laura Costabile, the Educational Facility Administrator at Stateville. After educators drop off their materials, it’s up to Costabile’s team to pick up the packets, label them with each student’s housing unit, sort the packets, and then pass them on to the prison’s resident law clerks, who take them back to the unit where they’re incarcerated. From there, an office sergeant delivers the course packets or makes sure the law clerks can do so.

Given that there are only four educators, including Costabile, working as part of the “little but mighty” educational staff at Stateville, and that they’re responsible for distributing course materials to over 150 students, “it’s going as well as can be expected during this unprecedented time,” Costabile said.

Despite the challenges that the pandemic has unleashed, Ross is proud of the work that her students have created during this turbulent time. One such student is Michael Sullivan, who has been incarcerated at Stateville since 1995.

In 2009, Stateville’s chaplain signed up Sullivan, who by that time already had a reputation as a self-taught artist, for a fine arts class through PNAP. That was the first PNAP class Sullivan took—and it was also how he met Ross.

On Sullivan’s very first day of class, Ross, standing next to a box of art supplies, introduced herself to Sullivan and his classmates “with this big warm smile,” Sullivan wrote in a message to the Weekly. During their first session they didn’t make any art, but Sullivan left thinking he might become a better artist.

Ross’s presence also made an impact on Sullivan. “And now eleven years later, she is the same warm and loving person,” he wrote.

The greatest lesson that Sullivan has learned through PNAP is that art is not necessarily about individual expression. “Collaboration is the seed of cause,” Sullivan wrote. “It can take you out of a state of selfishness to a mindset of selfless[ness].” Going forward, Sullivan would like participants in PNAP to obtain a fine arts degree, “because art is and will always be the past, present and future of our country.”

Johari Jabir, an educator with PNAP whose academic interests range from Black studies to cultural history and music, taught via correspondence a subject that one might not expect to translate well to the medium: mindfulness. He began developing a mindfulness class after students told him they were interested in learning how to cope with the noise and violence present in prison.

Prior to COVID, Jabir originally intended to both teach mindfulness practices and lead guided meditations. COVID knocked out the possibility of guided meditation, but Jabir was determined to salvage the possibility of the former. These practices were something he held near and dear to his heart: “I know what it does for my own politics of non-violence,” he said.

Jabir created a correspondence curriculum centered around the book The Untethered Soul by Michael Singer. Each week, he assigned his students to read a section of the book and answer some “very contemplative questions” he designed. Someone would pick up the students’ written responses from Stateville, and then Jabir would read them all. He typed out responses to each student that “would ask them to do a more guided sort of silence around the reading.”

He expected five students to enroll. Instead, around twenty students—whom he described as “very grateful but also very committed”—participated in the class, which lasted around seven weeks. Jabir said The Untethered Soul was a hit with his students. “Some of them said ‘I just read the whole thing in one sitting,’” he said. Since the students were on lockdown, what students learned in the class “really met the need of the time.”

PNAP is also how Hartsfield got involved with the HEP community. In 2015, while incarcerated at Stateville, he took a class titled “Freedom Dreams,” taught by Alice Kim, director of community building for PNAP, where he read an “intense book” by Ta-Nehisi Coates, according to a message he wrote to the Weekly. Later on, he applied to be a part of the UWW program, which attracted fierce competition: “2-300 applications, I’m told, went out, but only eight were accepted. I was one of those eight!”

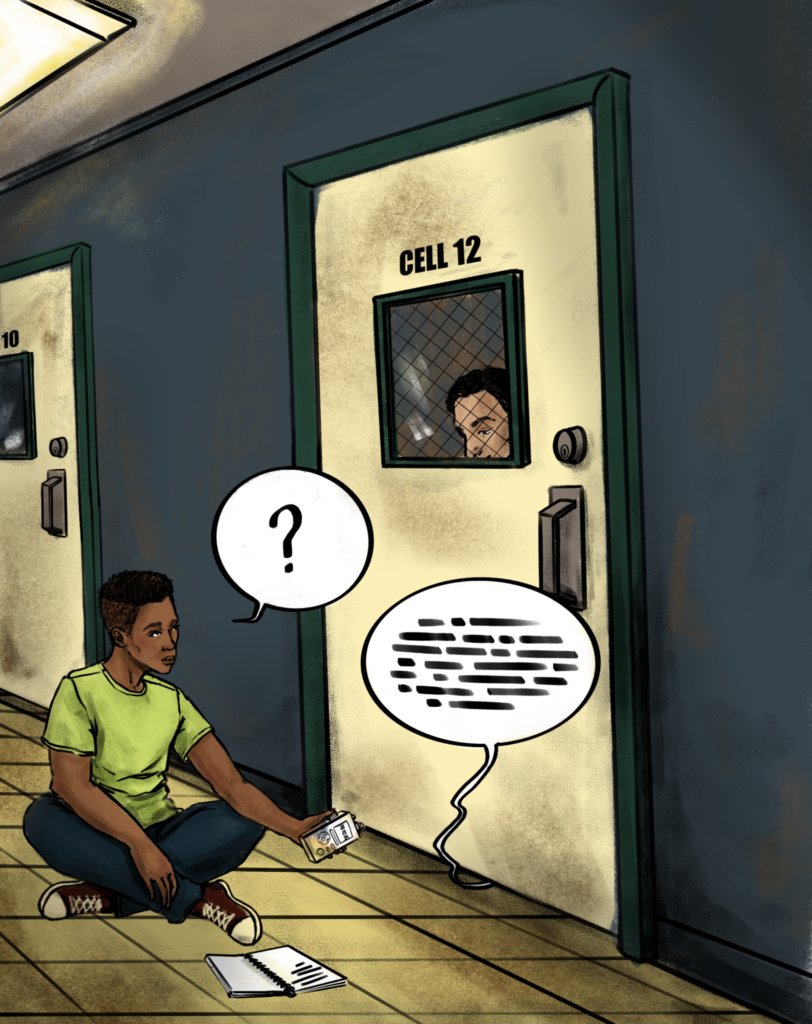

Hartsfield’s favorite experience as a UWW student was participating in an internship through Northwestern University’s Children and Family Justice Center. Despite being housed in a restrictive housing unit at the time, he interviewed fellow incarcerated people and gathered information about the juvenile justice system. “I had to conduct one-on-one interviews with individuals, sometimes through perforated doors, sometimes while they got their hair cut, or through the food slot in the steel door,” Hartsfield said. “Obviously this wasn’t the best part, but knowing that the work I was doing was going to make a difference was!”

Hartsfield has completed all his graduation requirements, including taking independent study courses, generating a writing portfolio, and delivering a twenty-minute presentation on what he learned. All that’s left for him to do to get his bachelor’s degree is to fill out some paperwork with NEIU.

Around the same time as Hartsfield began taking PNAP classes, Carl Williams started doing the same. Williams told the Weekly he took around thirty classes on subjects including on Black women’s studies, theater, theology, poetry, and restorative justice while at Stateville.“PNAP has just been a joy in all areas of life,” Williams said.

He was released from prison in August 2020, and credits PNAP with teaching him the skills he needs to be an effective communicator at his current job, where he sells cleaning supplies. He plans to stay involved with the criminal justice reform community, and aspires to return to prison as an instructor. “I would like to be able to be an educator who can help them continue to develop their goals and realize their dreams,” he said.

PNAP wasn’t the only Stateville program to switch to serving their students via correspondence. North Park University’s School of Restorative Arts switched to correspondence learning in April, according to Vickie Reddy, the program’s assistant director.

This semester, NPU is facilitating a correspondence class called “Black Faith Matters” for seventy incarcerated students. The participating students are each on track to earn a master’s degree in Christian Ministry and Restorative Arts from the North Park Theological Seminary.

Reddy believes that, as a program centered on ministry, NPU’s program was and continues to be “uniquely positioned” to weather the storm of challenges posed by coronavirus. “We’ve done the work of trauma and healing and non-violent communication,” Reddy said.

Because IDOC facilities have been on lockdown since March, students in the program haven’t seen each other in nine months. “They’ve not only lost the outside community,” Reddy said. “They’ve lost the community with one another.”

Despite that, though, some students are staying strong. “One of our students wrote a letter early on,” Reddy recalled. “And he said, ‘I just feel like all the classes that we’ve just done have been to prepare us for this moment.’”

Certain other parts of NPU’s educational programming, such as the performing arts cohort, have had to be put on hold due to the coronavirus. With the help of a few outside actors, the sixteen students enrolled in the cohort developed a performance piece centered around the idea of “redemptive storytelling.” The students had been scheduled to perform their creation at Victory Gardens Theater in August 2020; now, their performance at the theater is slated for July 2021.

NPU had also hoped to start a HEP program at Logan Correctional Center, a women’s prison thirty miles north of Springfield. That program’s debut has been postponed as well.

One of the “up-and-coming” programs that Burlet mentioned also pivoted to sending course packets to its students. During the spring, Benedictine University’s Inside-Out Program at Sheridan Correctional Center “shifted into triage mode,” said Rumpf, the sociology and criminal justice professor.

The realization that the pandemic would halt in-person classes “was like a one-two punch,” Rumpf recalled. First, IDOC announced the suspension of all visitors until further notice on March 13. Then on March 18, Benedictine University informed the campus community that all classes would be fully online for the remainder of the semester.

The program at Sheridan utilized an inside-out model to teach restorative justice—roughly half of the class consisted of incarcerated students, while the other half were Benedictine students who would make the trip inside each week with Rumpf. The final time the class met was on March 9; they had seven in-person meetings in total that semester. But the shutdown meant that the students in the class never had a chance to say goodbye to each other.

Rumpf and the students closed out the semester via correspondence. One of the first things Rumpf sent to her inside students was a letter reassuring them that the class wouldn’t go away. The students appreciated her effort: “It’s almost like they were surprised that people on the outside were still thinking about them,” Rumpf said.

Altogether, the outcome of the class could’ve been worse: all of the students completed their readings and finished their assignments. “For a really bad situation, I think it worked out pretty well,” she said.

The longest-running HEP program in the state, dating back to 2008, is the University of Illinois’s Education Justice Project (EJP), which serves students at Danville Correctional Center.

EJP’s impact on its students has been palpable. At a recent event hosted by IL-CHEP, Larry Barrett, a former student and current program assistant at Adler University, described EJP as being “like a unicorn.” He credited EJP with helping him come to terms with his masculinity in a space where people are “hypermasculine.”

EJP isn’t currently running any classes via correspondence, though. The group wrapped up its spring semester classes via correspondence in July and has since shifted its efforts to creating up-to-date re-entry guides and producing instructional videos, according to Rebecca Ginsburg, EJP’s director.

The initiative to create helpful re-entry guides is not a new one for EJP. Ginsburg traced the effort back to a meeting of EJP alumni in 2015, where alums brought up the fact they’d received little to no re-entry resources from IDOC when they were released. At first, Ginsburg wasn’t fully convinced. Then, the alums brought her the “multiple generations-old Xeroxes of re-entry flyers” they’d been handed by the state. “They were keeping it because it was a souvenir of how badly the state treated them,” Ginsburg said.

Since 2015, EJP has been producing and updating a comprehensive re-entry guide annually. After it became clear that COVID was going to affect the re-entry process, EJP began creating a COVID-specific re-entry guide. By May, that guide was ready to be distributed with the help of IDOC, which sent the guides to its facilities across the state. In total, about 8,000 hard copy COVID re-entry guides were distributed, and the guide is also available on EJP’s website.

Thanks to an emergency $1 million grant from the Mellon Foundation, EJP is also developing “instructional videos” to screen on the institutional TV channels that incarcerated people have access to. The videos will consist of recorded lectures by instructors in a wide array of subjects, from history to physics to English.

Ginsburg pointed out that the videos can’t possibly replace in-person instruction. But one small silver lining is that the videos can be broadcast to all 1,800 incarcerated people at Danville, rather than just the seventy students enrolled in EJP. Ginsburg hopes to get the videos to other IDOC facilities as well.

At least one university is using this time during the pandemic to move forward with its plans to start a new HEP program. In the fall of 2019, Adler University started engaging in discussions with IDOC in the hopes of offering classes at IDOC facilities from their soon-to-be launched online bachelor’s program in applied psychology. They’re currently planning a pilot program for that initiative, according to Dr. Michelle Dennis, the interim executive dean of Adler’s online campus.

The program would utilize a model that’s “probably unheard of,” Dennis said: the primarily asynchronous classes would enroll both incarcerated and not incarcerated students. The incarcerated students would be provided with tablets so they could access a learning management system, like Canvas, where they’d be expected to read discussion questions from their instructors and post responses to them.

The pilot program will include ten incarcerated students and no students from the outside world, so that program administrators can smooth out technical and other challenges before the program makes its official debut. For the pilot, an Adler faculty member will teach a 300-level applied psychology course using “exactly the same” syllabus as what would be offered in Adler’s online campus, according to Dennis. IDOC has yet to determine in which facility it will run the pilot.

Rich Stempinski,director of IDOC’s Office of Adult Education and Vocational Services, confirmed to the Weekly that IDOC is in “very preliminary discussions with Adler.” He said there are some technological and infrastructural challenges that IDOC needs to smooth out before more progress can be made on the initiative.

Dennis is currently working to secure grants for the program and hopes to start the pilot in June 2021. She wants to formally launch the program in the fall of 2021, thought she recognizes that that timeline might end up looking a little different.

When Dennis and her colleagues at Adler began planning for their online HEP initiative, there’s no way they could have anticipated that a global pandemic would have shut down in-person HEP programming. Dennis said she recognizes that “online education in prisons right now can serve an immediate benefit of filling the gap” that the pandemic has caused.

But she also warned against treating online HEP programs as a panacea. Dennis doesn’t want online HEP programming to replace face-to-face instruction in prisons when the pandemic is over, since “students who are incarcerated benefit from individuals coming into their facilities physically, to have that face-to-face connection…isolation causes many, many negative effects.”

Costabile hopes to add a third cohort of students to the HEP programs at Stateville. Originally, the plan was to introduce a third cohort this past fall, but COVID put those plans on hold. In addition, she’s concerned that there won’t be enough classrooms for three cohorts.

Rumpf is planning to run another iteration of the inside-out restorative justice class next spring. This time around, she’s planning on building in a way for the inside and outside students to communicate with each other, since that was one aspect of the class she had to scrap during last spring’s triage moment. She didn’t ask IDOC for permission to preserve communication between outside and inside students, because she “kind of assumed or knew it wouldn’t be a possibility,” due to the strict guidelines that IDOC has for its incarcerated students.

Jabir, the PNAP educator who taught the mindfulness class, affirmed that his “comrades in PNAP” are dedicated to their students, saying that “none of us is going to abandon the project.” Jabir plans to teach another class on mindfulness in the spring semester, this time at Cook County Jail in Chicago.

He also expressed a more long-term vision for PNAP, citing his abolitionist worldview. “I don’t know I’ll live to see the day, but I am there with them with the hope and vision that there won’t be a prison to have higher education in, that these will be eliminated,” Jabir said.

As for Hartsfield, he hopes that PNAP will be able to expand its programming to other institutions and acquire more funding. He’s also determined to go to grad school in the near future. If logistics and restrictions in the prison weren’t a concern, he would love to pursue a degree in sociology, psychology, political science, law, or education.

Despite the obstacles he faces in acquiring a graduate degree, Hartsfield recognizes that his education has had a positive impact on people besides himself. His son will be graduating high school early, he told Kim, his former professor, in a phone conversation. What’s more, Hartsfield is thrilled with how his son has taken a liking to creative writing, something made possible in part because he read some of Hartsfield’s writings.

“Man, if that’s the only thing that came out of this, I’m good with that,” Hartsfield said. “I’m completely good with that.”

Note: An earlier version of this story misstated the number of students enrolled in the NPU correspondence class “Black Faith Matters.” There are seventy students enrolled, not twenty. The Weekly regrets the error.

Lucia Geng is a student on leave from the University of Chicago who can be followed on Twitter @luciageng. She last wrote about rising rates of detention amid the pandemic at Cook County Jail.