Though the neighboring house, with its hoary cobweb wrinkles, has a scarier face, the lemon merengue-colored Victorian house is where the phantoms live. The street curls in the Chicago humidity and dissolves into a lake-bitten fog.

The ghost of Ben Hecht peers out the window of the sardine-can room where he used to sleep and write. Twenty-six years old, eyes sunken as a roadside ditch; he floats through the wall, pallid moustache quivering.

He moves slowly on his dead legs. The Hyde Park street is a stranger. Now, the three-headed Cerberus of MAC Property Management offices, Wingers fine dining, and Zberry frozen yogurt shop guard the entrance to his underworld existence.

He remembers the nocturnal strolls, brain chewing on the faith of fishermen, the tragic feet of flappers, the moldy juice joint philosophers.

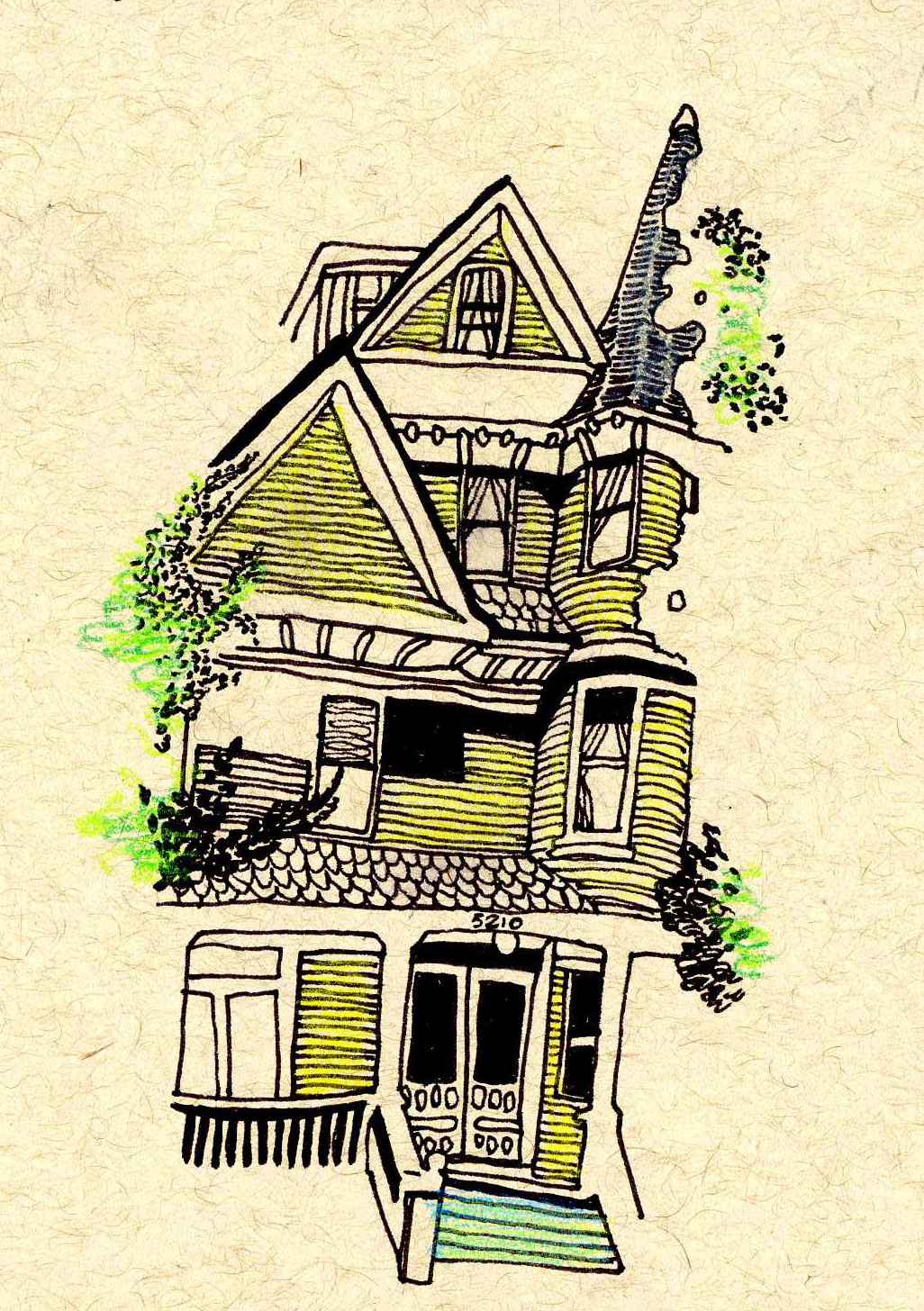

Literary allusions, odd words, and a somewhat farcical philosophy were characteristic of Ben Hecht’s famous “1001 Afternoons in Chicago” column for The Chicago Daily News, which he wrote while a boarder at the large yellow Victorian on the 5200 block of South Kenwood Avenue during the early 1920s.

His editor, the iconic Henry Justin Smith, illustrated the importance of Hecht’s literary masterpiece, highlighting his attention to the fleeting, unexamined perfect imperfection of city life—“The idea that just under the edge of the news as commonly understood, the news often flatly unimaginatively told, lay life; that in this urban life there dwelt the stuff of literature.”

Hecht lived with his friend and collaborator Charles MacArthur and frequented the Jackson Park art colony that had developed just a few blocks away on 57th Street, seekers of a bohemian lifestyle who paid cheap rent to inhabit former restaurants and concession stores built for the World’s Columbian Exposition. The mustachioed screenwriter-director-producer-playwright-literary journalist Hecht went on to win the first Academy Award for screenwriting, cementing his status as a Hollywood legend. His impressive resume includes defining the gangster movie genre as screenwriter for Underworld and Scarface, writing scripts for two of Hitchock’s psycho-drama masterpieces, Notorius and Spellbound, and being the primary script editor for the epic Gone with the Wind. A fixture in glamorous Hollywood circles, he has been credited with ghostwriting Marilyn Monroe’s autobiography My Story. The literary giant’s old home on Kenwood is now a private residence for a family of six with a dog. In the same way that he poeticized the underbelly of the industrial new Chicago, Hecht’s life story makes a fairy tale of the unassuming block.