Recent census reports show that Chicago’s population of humans decreased by almost 3,000 between 2014 and 2015; this data suggests that within a decade, Houston will replace Chicago as the third most populous city in the United States. But at the same time, Chicago is becoming more and more of a hotspot for another species—rats.

According to a recent article in USA Today, more than twice as many rat sightings have been reported in Chicago this year as have been reported in New York, which has more than three times as many humans as Chicago. Orkin, a nationwide pest control service, rated Chicago the country’s “rattiest” city based on the number of rodent treatments the company performed in 2013. (Houston lagged far behind at number 13).

Over the past few years, the number of rodent complaints in Chicago has risen dramatically. The city’s 311 department logged about 7,500 rat-related calls in the first quarter of 2016, up from around 3,000 complaints in the first quarter of 2014. In an interview with Chicago Tonight earlier this year, Mayor Rahm Emanuel acknowledged that the growing rat population has become “a real problem.”

“I think it’s a real problem because it impacts the quality of life of the people,” he added.

The Emanuel administration has made a number of efforts over the past year to address the city’s growing rat problem. These included hiring more technicians to hunt down rats, proposing fines for residents who don’t clean up garbage and animal waste, and encouraging developers to consider rat-proof construction techniques.

But for Ronald Worthy, a twenty-five-year veteran of the pest control industry, these measures aren’t enough. Worthy says the city of Chicago has “stopped being aggressive about [its] rodenticide program,” easing off on the use of “quick-kill” poisons in favor of poisons that only make rats temporarily sick. Until the city gets merciless, Worthy says, they won’t make any headway.

Worthy is the founder and CEO of Good Riddance Pest Management, a pest control operation with locations in Douglas Park and Riverdale. For him, the war on rats isn’t just a matter of numbers: he sees the battle from the trenches. Over the years, he’s seen up close and personal just how irritating and harmful rats can be: he says the animals can defecate up to fifty times a night, and they urinate everywhere they go so that they can follow the trail. Some rats have even been known to bite babies, seriously harming them.

Worthy estimates he’s killed thousands of rats personally, and baited many more than that. “There’s a lot of ways of killing them, and I’ve used them all,” he says. He believes that the proper approach to fighting rats is a holistic one that understands how rats work and what they need to survive.

“Really what you need is integrative pest management,” Worthy says. “You can’t just go in and kill them over and over, you need to take away what they need—protein-based foods and a harborage area. There’s got to be a reason they’re there in a certain place. They don’t just say, ‘I’m going to set up at Joe Blow’s house.’ ”

In an interview with USA Today, deputy commissioner of the Department of Streets and Sanitation Josie Cruz lamented the city’s inability to implement such an “integrative” approach. Cruz said the city’s attempts to poison rat burrows won’t be effective until residents stop leaving other food for rats to take instead. Comparing breadcrumbs to rodenticide, she said, is “like steak to a hot dog.”

“The rats are there because they are feeding on something,” Cruz said. “They’re not there because they like the neighborhood. They are there because of the food source. If you cut off that food source, they’re going to eat rodenticide, and you’re not going to have that problem.”

Removing such alternative food sources seems like a good place to start, but the logistics have run into some political roadblocks. On May 12, the City Council’s Health Committee approved a resolution that would fine residents who don’t clean up dog poop daily. In addition to reducing the amount of poop in city streets and yards, the resolution was aimed at taking away a principal food source for rats: poop. One of the resolution’s most vocal supporters was 20th Ward Alderman Willie Cochran, who claimed to have residents in his ward with backyards containing up to fifteen pounds of dog feces—a prime food source for rats, he said.

46th Ward Alderman James Cappelman disagreed, arguing that rats would much rather eat “berries, birdseed, or even baby rats” than eat dog poop. When the resolution was brought to the full Council last week, the Council chose to table it for a month, citing concerns about policing residents’ backyards.

But Matthew Combs, a doctoral student at Fordham University who studies the population genetics of rats, thinks even the dog poop theory might not add up to much.

“I’m not sure if it’s because of all the dog crap on the sidewalk,” he said. “Rats will eat disgusting things, but they much prefer to eat fresh food that’s high calorie.…Sometimes I think that someone comes up with an idea, like, ‘Dog poop. That makes sense!’ and they just kind of run with it. And then we’re going to talk about dog poop for two years.”

As long as dog poop and other food sources abound in the city, even intense extermination efforts won’t make much of a dent. This year especially, Worthy says the outlook isn’t good: he says a mild winter meant there was nothing to hinder the city’s rats from breeding. Combs agrees with this assessment.

“A city doesn’t have a steady rat population, rats have such high mortality, the turnover rate is so high,” he said. “But if the winter is less harsh and more survive, then you’ll see more babies in the spring. After a couple of mild winters, you may see an increase in that.”

And boy, can these rats breed. A female rat can give birth to as many as six litters a year, and each litter can have as many as nine pups. Moreover, it only takes two or three months for female pups to become old enough to start breeding themselves. This means that over the course of a year, a single rat could have hundreds of descendants.

Moreover, since rats aren’t indigenous to America (they were brought over from Europe on boats), they have no natural predators: dogs don’t see them as a food source, cats “aren’t going to do it,” according to Worthy, and there aren’t nearly enough coyotes or wolves to bring down the rat population.

Worthy takes a historical view of this current surge in rat population, which he says has been in the works since long before the Emanuel administration. He believes the destruction of the city’s high-rise public housing projects deprived Chicago’s rats of what had been massive, centralized sources of food. Worthy recalls these high-rises, and public housing generally, as one of the toughest battlegrounds he’s fought on as an exterminator: he described entering the incinerator room at the Dearborn Homes and finding it had been taken over by rats who had gotten so confident they would literally take food out of his hands.

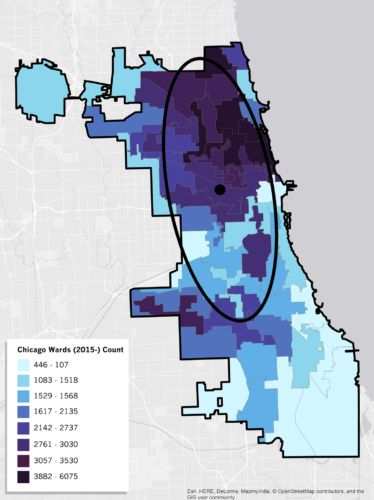

The above map provides a visual representation of all calls made by Chicago residents to 311 about rodent-related issues from January 1, 2013 to May 8, 2016. The data visualized represent over 115,000 calls made during this time period, records of which were obtained using the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) and the City of Chicago’s Data Portal.

It compares the number of calls made about rodents in each ward from January 1, 2013 to May 8, 2016. The pale blue areas represent wards with the lowest call volumes, while the dark purple areas represent wards with the highest call volumes. These high-volume wards are clustered on the North Side, while wards with lower call volumes are concentrated on the South and West Sides. Despite this trend, high-call volume wards are present outside of the North Side: the 13th and 11th Wards have call volumes in the thousands. Interestingly, the 42nd Ward, which contains parts of the Loop, River North, and the Gold Coast, is the only ward north of Roosevelt with the palest blue designation.

When the projects came down in 2011 (though Dearborn Homes were renovated and are still standing), Worthy says the rats scattered across the city, looking for new homes. He believes the saving grace of these rats was the restaurant boom Chicago has seen over the past twenty years. Many restaurants dump leftover food without properly sealing their garbage cans, which provided the city’s rats with “harborage areas” and guaranteed food sources, and allowed them to spread across the whole city.

“How continuous is this population?” Combs asked. “It’s pretty continuous, already [in big cities]. They’re pretty connected through the city.” Combs explained that many rats become “dispersers,” traveling from neighborhood to neighborhood. These migrations cause routine population booms in new areas, through what Combs calls—Lord help us—“invasion events.” Worthy, who claims he has responded to extermination calls in every neighborhood, agrees that the problem is citywide.

Seeking to find out whether the city’s rat population is more concentrated in some neighborhoods than others, the Weekly conducted a data analysis of all “rodent baiting” service requests made to 311 since the beginning of 2013 to May 8 of this year. Wards on the North Side have a far higher volume of rodent baiting requests than do most wards on the South Side (see map), but that doesn’t necessarily mean there are more rats on the North Side: it just means more people call 311 on the North Side.

The Weekly conducted a further analysis, considering rodent calls as a proportion of all the 311 service request data available on the city’s data portal. This included some 12 different categories of request—pot holes, graffiti, street lights, etc. This analysis revealed that a far lower percentage of 311 service requests are rodent-related in South Side wards than in North Side wards. In the 7th, 8th, and 9th ward, for example, less than 2% of calls were related to rodents, and in the 10th Ward only 1% of all calls were rodent baiting requests. On the North Side’s 44th Ward, by contrast, 18 percent of calls were rodent baiting calls, with the nearby 43rd and 46th Wards coming close at 16% and 12% respectively.

Worthy theorized that the greater number of vacant and abandoned buildings on the South and West Sides may mean there are huge numbers of rats that are going unseen because they aren’t being reported to the city or combatted by exterminators. He says rats are very territorial: when they can, they’ll try to establish control over areas of around one hundred square feet. Vacant homes, then, provide ideal hideouts: the rats are close to food sources, but safe from meddling humans.

In the end, though, he thinks the disparity in 311 data is more likely related not to the number of rats, but to the way residents respond to rats.

“It’s my personal belief that they’re more tolerated on the South and West Sides,” said Worthy. “People will say, ‘Oh, it’s just a rat.’ On the North Side they say, ‘That’s a rat! Aah!’ but in poorer communities they’re more apt to deal with it, and, furthermore, the city is more apt to respond to people on the North Side.”

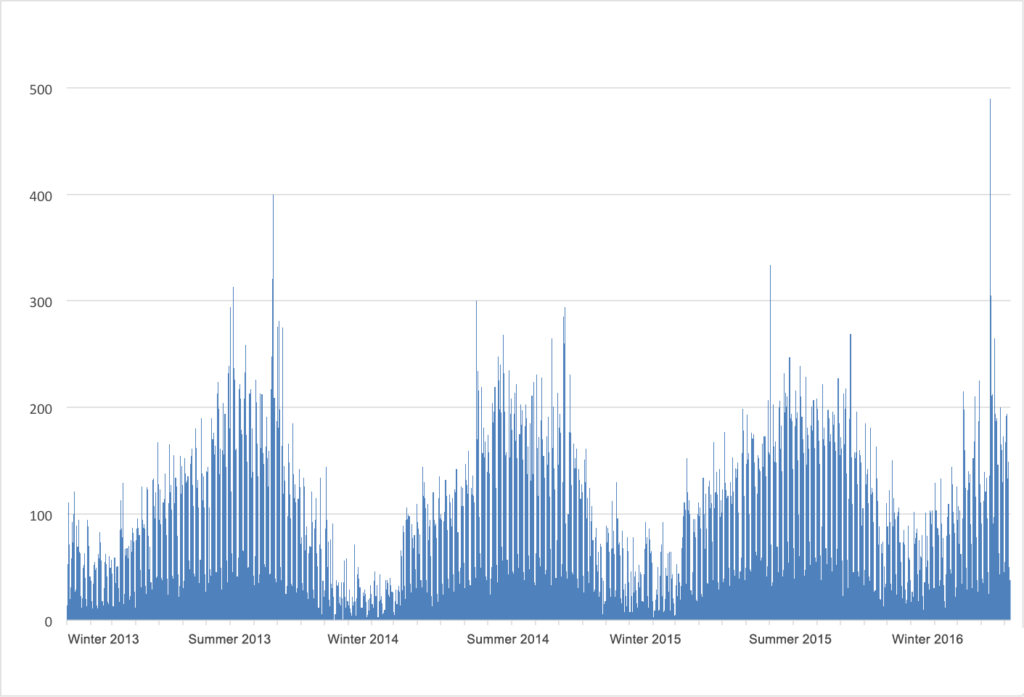

This graph visualizes the number of calls to 311 about rodents made every day from January 1, 2013 through May 8, 2016. From first glance, it’s easy to see that there’s a cyclical look to the graph: the number of calls peak during the spring and summer months and plummet during the fall and winter. According to Matthew Combs, this reflects rat mortality and reproduction rates, which increase in the winter and summer, respectively. Seasonal peaks 2013-2015 are pretty similar, with the 2013 and 2015 peaks looking slightly more similar. The valley that typically formed between November and April in the first three years was not as extreme during winter 2016. This can be a result of the mild winter weather, says Combs, since rats are less likely to suffer a decrease in population size when conditions are better, meaning that more survive the winter to reproduce in the spring and summer.

Of the 1224 days worth of calls the Weekly analyzed, there was only one day, December 14, 2013, in which nobody in the city of Chicago called 311 about rats. In stark contrast, 490 calls were made on April 12, 2016, 311’s busiest rodent-related day since January 1, 2013. An average of 94.7 calls were made each day across the city for the period of time this dataset spans.

A study published in the Journal of Community Psychology concluded that among low-income residents of Baltimore, residents who reported daily rat sightings were less likely to believe that rats were a significant problem on their block. “In models controlling for significant demographic and neighborhood variables,” the study concluded, “those reporting frequent rat exposure…were less likely to know how to report rats to the city, and were less likely to believe the city would act if notified.” One thing residents in various neighborhoods didn’t differ on, though, was their attitude toward rats in general—nobody likes them.

But for Worthy, rats aren’t as devilish as humans make them out to be—they’re about as afraid of humans as a human would be of King Kong. After twenty-five years, he’s not afraid of rats anymore—indeed, he thinks most people’s hatred of the creatures is unjustified.

“The idea that they’re creepy, that’s just culture,” he says. “In some places, people do have rats as pets. In some places, they’re revered as gods. With our beliefs, traditions, we don’t like rats…you can go back to the 1800s, 1700s, whatever, when they had the plague. But it wasn’t a rat that carried the plague, it was the fleas on the rats. I’m not here to kill all the rats. What I am here to do is keep the rats out of people’s lives.”

The above map visualizes the more than 115,000 calls made by Chicagoans to 311 about rodent-related issues from the beginning of 2013 to May 8, 2016. Each blue point on the map represents a call made, with bright blue areas representing a spike in calls. As time elapses, notice how the number of calls drops off during the winter months and spikes during the summer months. The wintertime drop in calls was less severe during this past winter, potentially as a result of the milder weather.

great nice work