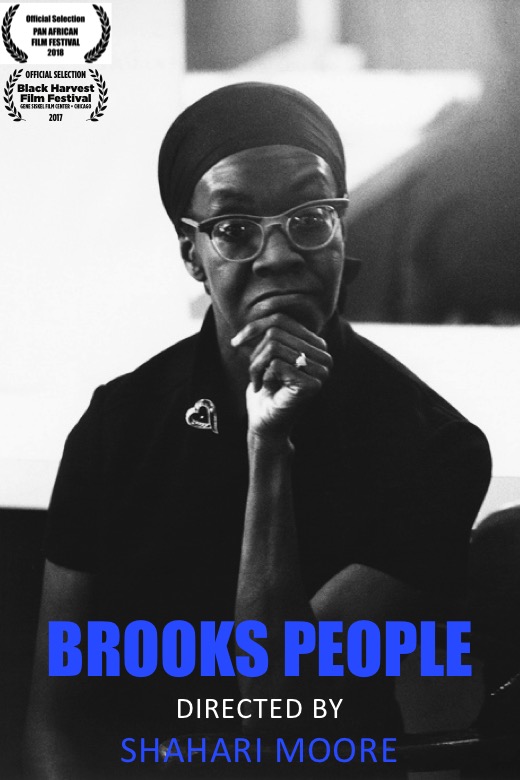

When we’re talking about Gwendolyn Brooks, we are talking about material that will essentially educate and material that will leave a legacy,” said writer and documentarian Shahari Moore. Her solo directorial debut, Brooks People, a twenty-minute documentary exploring the work and lasting impact of Brooks, the first Black writer to win a Pulitzer Prize, premiered at the Gene Siskel Black Harvest Film Festival last year. To illustrate her outsize influence on the South Side and across the country, Moore interviewed numerous contemporaries of Brooks, including esteemed scholars, poets, and artists such as Dr. Cornel West, Nikki Giovanni, and Haki Madhubuti—as well as Brooks’ daughter, Nora Brooks Blakely.

Brooks’ literary contributions spanned most of the twentieth century, tackling what her eyes drank in on a daily basis. Her focus on the lives of Black and brown folk—raw, destitute, and golden amid sadness; colorful in all of its complexity and phases of pain, hopefulness and resilience—never wavered.

She was intrigued by people and drawn to the happenings in her neighborhood. Her volumes of poetry have a way of detailing the Black urban experience that is unapologetic and tell the world, without sermonizing, “who we are, and…how we do it,” as Giovanni told Moore in Brooks People. Brooks herself told Ebony Magazine in 1987, “Look at what’s happening in this world. Every day there’s something exciting or disturbing to write about. With all that’s going on, how could I stop?”

Brooks People opens with footage from an interview the writer did with WTTW in 1966, titled “The Creative Person.” Moore discovered the archival taping about four years ago and immediately thought, ‘This is a piece of gold,’ she told the Weekly in an interview. “For me, it laid out a beginning, middle, and end. It gave us a physical presence and it also gave us insight into her personality, which is something you can’t get from any of her photos. Oftentimes, when you see her reading, there’s a seriousness that comes across her.”

This introduction threads the narrative Moore is intent on bringing to the forefront, one that seeks to “help the audience get to know Gwendolyn Brooks as a person,” she said.

“I wanted to have a better understanding of her life,” Moore continued. “What I found is that, in the initial interview, you actually get a lot of playfulness. It’s my understanding that, that is very much who she was. Serious about her craft and who she was as a person, but always had an element of play about her.”

A separate audio recording showcased in the documentary teases Brooks’ “playful” personality. When detailing how she met her then husband-to-be Henry Blakely, whose interest in her had been piqued upon hearing about her poetic skills, Brooks jokingly advised young girls to “start writing poetry” if they desired to get married.

The documentary also weaves in the writer’s deepening awareness of her role within the Black community. In 1967, during the burgeoning of the Black Power and Black Arts movements, Brooks attended the Second Black Writers’ Conference at Fisk University, a historically Black university in Nashville. There, she interacted with younger poets whose rhythm and rhymes had a more direct approach in responding to the state of society. She listened intensively to the radical stanzas and message-driven verses. Following the conference, she felt a charge that would forever shift her work from structured sonnets to a freeform flow with a political edge. The following June, her powerful collection In The Mecca was released, exemplifying Brooks’ concern and care for social issues.

In Brooks People, Nora Brooks Blakely draws attention to her mother’s poem “Patrick Bouie of Cabrini Green,” which is about a sixteen-year-old boy shot in the former public housing development. She distinctly points out her mother referencing Bouie as “Our Interrupted Man” in the text. It’s a heart-wrenching label that stings when considering the violence that continues to plague Black and brown communities, often claiming young lives.

Using video from local and national protests, along with poignant commentary from Madhubuti—the legendary Chicago author, educator, and publisher who sustained a decadeslong professional and personal relationship with Brooks—Moore said she addresses “violence we’re seeing in our communities, against our communities, and coming out of our communities,” and how Brooks dealt with it through her writing and activism.

With its use of vintage and modern media, accompanied by youth performances of Brooks’ work, Brooks People intriguingly bridges generational gaps and brings forward the relevance, importance, and connectivity of Brooks’ writing in today’s socio-political climate. As part of a series of one-line praises from interviewees included in the documentary, Dr. Cornel West said, “The poetry of Gwendolyn Brooks is more powerful now than ever.” Dr. Randall Horton, a member of avant-garde jazz group Heroes Are Gang Leaders, christened her “the first urban poet.” And Kevin Coval, poet and director of Young Chicago Authors, proclaimed that “if it wasn’t for Gwendolyn Brooks, we would not have hip-hop.”

Moore takes this opportunity to showcase the lineage from Brooks’ poetry to the rise of the Black Arts Movements poets she mentored, followed by the emergence of spoken word artists The Last Poets and Gil Scott-Heron. She continues showing the evolution of the genre with a segue into performance footage from a Gwendolyn Brooks conference in Chicago featuring emcees Common, Talib Kweli, Kanye West, and his late mother Dr. Donda West speaking about Brooks and her influence on music.

The praises stand as a testament to Brooks’ ability to sharpen minds, open universes, and reach souls with her evocative poems and prose. It’s the power of her art, influence, authenticity, and legacy. It also speaks to her unwavering determination to illuminate the Black community while simultaneously offering a noble lesson: always reach back and lift up the next.

“I think it’s hard to leave a legacy behind unless you can show the next generation their entry point,” said Moore. “One thing [among the many] that I admire about Gwendolyn Brooks is that she [was] focused on her craft and who she [was] as an artist, but she was also very communal in the provisions of opportunity and development for other artists. It’s a model for us. Unless we’re bringing someone else along, that legacy starts to disconnect.”

In Brooks People, Moore cohesively stirs a foundation of topics she plans to expand upon in her debut feature film, Cool: On Gwendolyn Brooks, which is currently in production.

Throughout Brooks’ life, the pen never existed idly while in her presence. And though the great Gwendolyn Brooks is no longer here with us after succumbing to cancer in 2000 at the age of eighty-three, she lives through her legacy.

According to Giovanni, “Writers don’t die. Our bodies transform. We go off to the ancestors. But writers don’t die because, their work lives. Generations that come up, continue to hear the poetry. Continue to read the poetry.”

Brooks People will screen next on June 9 as part of “The Gathering: Charles White and the South Side Community Art Center,” a celebration of Black Chicago Renaissance painter White’s work. South Side Community Art Center, 3831 S. Michigan Ave. Free with registration. (773) 373-1026. sscartcenter.org

LaToya Cross is a contributor to the Weekly. She is a freelancer with a love for arts, culture, poetry, and entertainment. She last contributed a profile of contemporary artist Nikko Washington in March.