In this dystopian present, it seems like more and more folks are seriously considering the possibility of a radically new future. The pandemic and the uprisings against police violence and white supremacy have uprooted the status quo. Changes in day-to-day work, commerce, and recreation brought about due to the pandemic have spurred more discussions around large structural changes to society, such as universal healthcare, universal basic income, and the abolition of prisons and police.

But of course, some people have been envisioning new futures—and doing the work to actualize them—for years and decades. At the South Side Weekly, we talked with five folks who have been thinking and doing the work of building new futures through their work as artists, abolitionists, designers, and organizers. This piece is not about the new futures they are imagining, but is instead about what processes and tools they use. Based on their input, we’ve created prompts for you to fill in. We hope you’ll see these activities as a way for you to think about what new futures you want for yourself and your communities.

You can listen to excerpts of the interviews with these five people and do a set of audio prompts in the “Envisioning New Futures” series on SSW Radio at soundcloud.com/south-side-weekly-radio.

[Independent, local journalism has never mattered more. Please consider supporting our work today, and NewsMatch with double the impact of your donation.]

Lorin Jackson

Lorin Jackson is a design consultant who studied interior architecture. This summer, amidst the uprisings against police violence and white supremacy, Lorin and her friends started Imagine Chicago 2020, a campaign aimed at getting communities to think about alternatives to policing. Part of that campaign involved wheatpasting posters of envisioned futures of public safety, affordable housing, healthcare, and public welfare at The Forum in Bronzeville.

Lorin’s also spent time working with young people and helping them cultivate their design thinking skills with organizations like Chicago Mobile Makers. I was interested in what tools from her work teaching design could translate to envisioning new worlds.

“Deep observation,” Lorin told me.

It starts with observation, but has to go beyond that: “I think a lot of times people may face a problem and not question it enough. They’re not questioning it to get to a point of starting to come up with solutions.” Part of her design process involves seeing the problem, documenting it, and then manipulating it. In her work with Chicago Mobile Makers, Lorin encourages youth to use simple materials like pencils, paper, and scissors to design solutions to the problems they’ve observed.

Lorin emphasizes that everyone has the personal agency to make change. “Whatever’s out your window might be boring to you. But if you think about it in a new way, it could offer some kind of possibility.”

H Kapp-Klote

H Kapp-Klote started the speculative fiction oral history podcast Working 2050 because he was burnt out. H cared deeply about his job; he was supporting community organizers in telling their stories by doing communications work for social movement campaigns, and had started doing that work because he wanted “to change the future.” But day after day, he felt miserable. He no longer felt like he could change the future.

H began reading a lot of science and speculative fiction from writers like Octavia Butler, Ursula K. Le Guin, N.K. Jemisin, and adrienne maree brown. Although the technologies and environments of the characters were different, the feelings in the stories mirrored some of the feelings H was experiencing day in and day out. H believes that seeing stories reflected back at us can help us transform what we do.

On Working 2050, H uses fictional stories about work in the future to reflect on work in the present. He drew inspiration from Studs Terkel’s now-classic 1974 oral history Working: People Talk About What They Do All Day and How They Feel About What They Do. In the Working 2050 episode “Pathfinder,” H explained to listeners that “when we imagine what the future could feel like—how people will feel about what they do all day—we get a little closer to changing that future for the better.”

H, who has contributed to an op-ed in the Weekly, said that the pandemic has already changed people’s perception of what change is possible in their day-to-day routines, because they’ve had to imagine it and implement it every day.

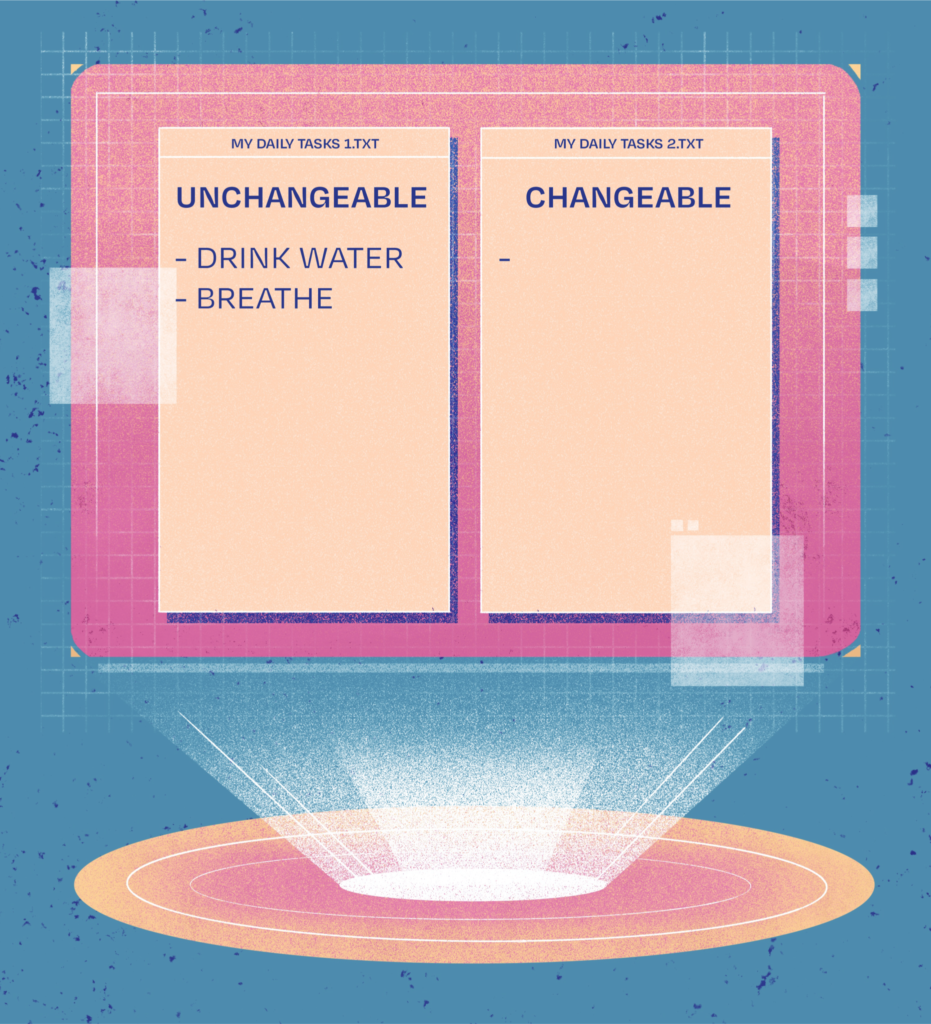

“Think about your day-to-day. Think about how it’s created and what about it could change and what about it is fixed. What of it is in your locus of control?”

Benji Hart

Benji Hart is an author, artist, and educator working towards Black, trans, and queer liberation. Their interdisciplinary work is all about envisioning new futures. Benji sees police, prisons, and military abolition as central to liberation. They’re currently working on a piece called “The World After This One,” which uses spoken word and movement to examine “the ways that Black folks have historically used the materials of the present to imagine futures where Black people are free, even when the materials of the present are a source of Black oppression.”

When we spoke about what processes Benji uses when envisioning new futures, they say they look to the past; that there are examples of liberation to be found in previous generations. Particularly as a Black, trans, gender-nonconforming person, Benji thinks a lot about the past before colonization, imperialism, and global capitalism. “My ancestors were living in balance in a different kind of way,” they explained. “Folks like me were safer at other points in history than we are now. Rather than imagining that Black trans and queer people have always been unsafe, have always been targets of violence, have always been living under the threats of harm, for me, it’s so important to look to the past, to remember that in my own ancestry, there were times that we were revered, there were times that we were safe, there were times that we were protected and valued and validated as who we were.”

For Benji, creating a future of liberation means, on a personal level, recognizing activities, relationships, and moments that bring them joy. “Once you know that feeling,” they tell me, “you know to look for it in other places. And you know deeply when you’re not feeling it. You know when you’re far from it.”

Putting your time, energy, and other resources into things that bring you joy, and avoiding things that don’t, is a path towards a future of liberation.

Chris Rudd

Chris Rudd tells me that when he was growing up, his parents were always considering two different futures simultaneously: the probable and the preferred. His parents knew that, as a young Black man, he would at some point have interactions with police. Chris’ parents offered him scenarios from a probable future encountering police, and gave him tools to help him survive those interactions.

At the same time, his parents were deeply committed to anti-racist work and got Chris to imagine a preferred future free from police harassment and violence. “I think it’s super interesting that Black folks, and I’m sure Latinos too, and other marginalized groups, we’re always consistently imagining two futures at the exact same time and then creating scenarios in which to interact in those futures.”

For Chris—a designer by trade—one of the major challenges in getting people to envision the preferred future over the probable one is time. His work involves bringing design tools to communities of color, and for him, that means giving people space to just stop and think about what their preferred future looks like.

In the summer of 2019, Chris and a team from the Illinois Institute of Technology’s Institute of Design set up a space in Bronzeville’s Boxville. They invited folks to fill in the blank for the following statement: “The future of _____ has to be different than the past.”

“Every time people saw that,” Chris says, “they stopped for a couple of minutes and just said, ‘this is like the hardest thing I’ve ever had to answer.’” This surprised him. He knew it was a thought-provoking question; but he didn’t think it would deeply challenge folks. “When I crafted that statement, it was to really make people think about what was the most important thing that had to be different for a successful community.”

Chris says that the prompt—because there’s only one blank space—really makes you think about the most important thing in your preferred future.

Chandra Christmas-Rouse

Chandra Christmas-Rouse remembers experiencing a lot of cognitive dissonance when she—a Black woman—entered the field of urban planning, a field that has historically been particularly insidious to Black communities. Early in her career, Chandra says she was trying to bring gender and race theory to urban planning, but now that’s reversed. She’s bringing the tools of urban planning to struggles for liberation. “I think about what type of city and what type of built environment looks like that truly has freedom at its core.”

This summer, Chandra was announced as a recipient of the Threewalls RaD Lab+Outside the Walls fellowship, an award that supports nine fellows imagining “alternative ways towards racial equity through the lens of radical imagination and racial justice.” Chandra’s work for the fellowship focuses on her neighborhood of Bronzeville and seeks to answer the question: “What if, when we dream, our neighborhoods gave us everything we need to realize our collective visions?”

When Chandra and I talked about envisioning new worlds, she told me that her vision for the future is always rooted in the past. “I am never starting from scratch. I’m drawing on so much dreaming and work that has been done to get us to this moment.”

For Chandra, the question:“what kind of ancestor do you want to be?” gets at the core of envisioning new futures, because it requires people to think about values, culture, and tradition. Values are principles, standards, or the things people think are important in their lives. Culture is “the ways that you put [values] into practice in the world.” Tradition is culture passed down from generation to generation. Thus, values serve as a foundation for culture, which is the foundation for tradition.

Asking the question “what kind of ancestor do you want to be?” allows you to think about what important aspects of your daily life and interactions within your community could be perpetuated as traditions in the future.

Erisa Apantaku (@erisa_apantaku) is the executive producer of South Side Weekly Radio. She recently helped produce a piece on West Side youth organizers.