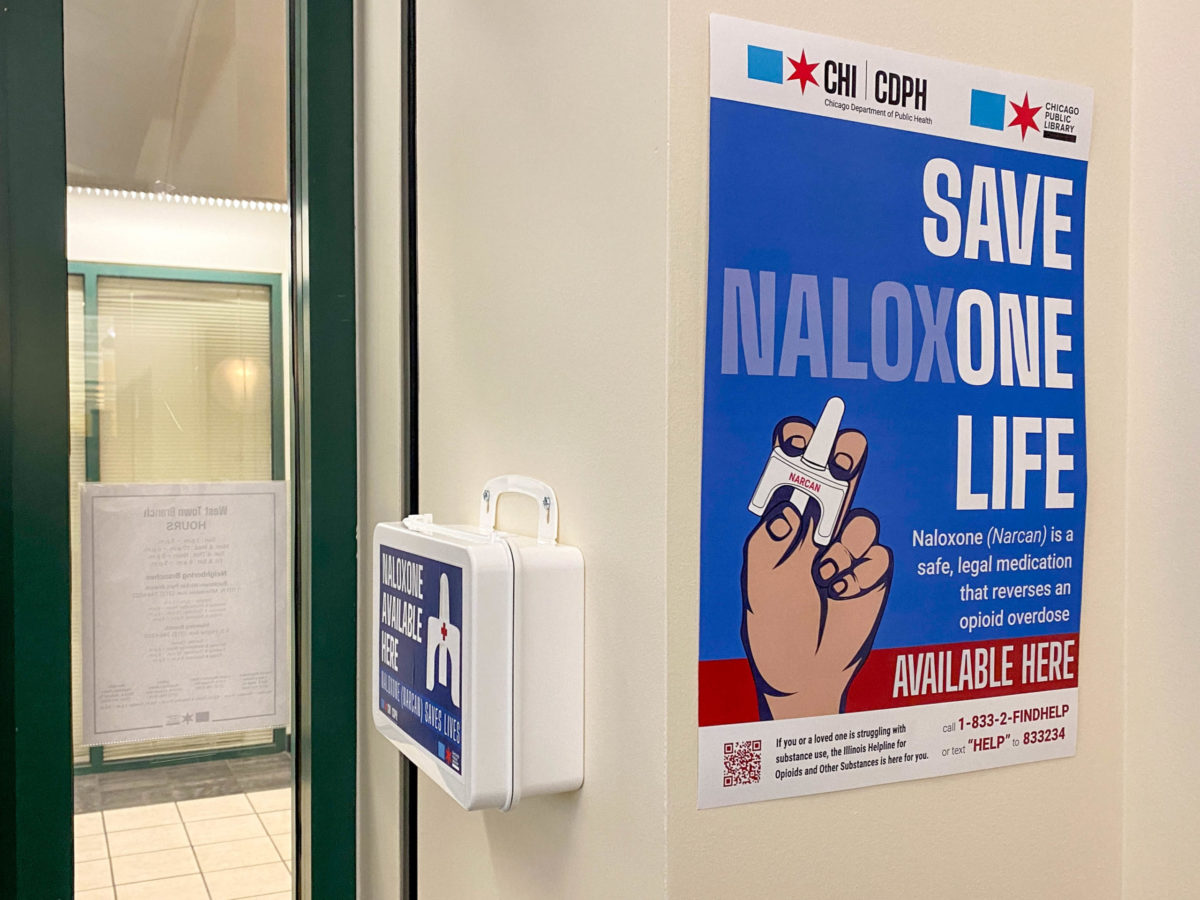

Inside the front doors of the Chicago Public Library branch in Austin, there’s a sign that reads “save (nalox)one life.” Below it, there’s a plastic container that looks like a first aid kit affixed to the wall. The box is labeled with bold letters that read “naloxone available here.”

The library location in the West Side neighborhood is one of fourteen branches across the city that started stocking Narcan, the brand name of the overdose-reversal medication naloxone, in early January. The partnership between the city’s library system and the Chicago Department of Public Health (CDPH) is aligned with similar efforts across the country as communities attempt to address the ongoing opioid crisis.

The idea for the Chicago initiative began last fall, when CDPH data continued to show “extremely high rates of opioid overdose and opioid fatality,” said Sarah Richardson, a grants research specialist in the health department’s office of substance use.

In December 2020, the Weekly reported on the correlation between the rise of homelessness and the uptick of street overdoses during the pandemic, as well as the creation of the South Side Opioid and Heroin Task Force, which was modeled after a West Side task force composed of medical and drug treatment experts.

According to CDPH, 1,303 people died of an opioid-related overdose in 2020 in Chicago, which was a fifty-two percent increase over 2019—the highest number of fatal overdoses ever recorded in the city.

Richardson and her team began thinking of ways to get Narcan, which she called “our first tool when we’re addressing the opioid crisis,” into more people’s hands.

“One of the first thoughts we had was libraries because they are open to everyone,” Richardson said. “They are in every community in Chicago, and they are really just this kind of community institution where folks can access all kinds of resources.”

The health department initially identified fourteen branches in communities with the highest number of Emergency Medical Services (EMS) runs for overdoses and overdose fatalities, which are all on the city’s South and West Sides. They then began training staff members at those library locations on how to use Narcan and recognize the signs and symptoms of an overdose.

The initial branches to have Narcan available on site are: Austin, Chicago Bee, Coleman, Hall, King, Legler, Manning, North Austin, R.M. Daley, South Shore, West Chicago Ave, West Englewood, West Town, and Whitney Young.

“As we continue to thoughtfully examine the ways our libraries support the neighborhoods we are in, this partnership to offer Narcan at library branches is a natural fit,” Chicago Public Library Deputy Commissioner Maggie Clemons said in a press release.

Two months after launching, the effort is expanding and thirteen more branches will have Narcan available this month. The added locations are Douglass, North Pulaski, Humboldt Park, Toman, Avalon, Brainerd, Greater Grand Crossing, Jeffrey Manor, Kelly, Pullman, Sherman Park, Thurgood Marshall, and West Pullman.

In 2017, Denver became one of the first cities in the country to stock Narcan in its public libraries after a 25-year-old man died in a library bathroom, according to reporting done by Colorado Public Radio.

“Do you let somebody potentially die? In your building? When you could have just sprayed something up their nostril and potentially (saved) them? To me that’s a pretty easy decision to make,” Denver’s city librarian, Michelle Jeske, told the radio station at the time.

Jeske told the Weekly that library staff across Denver’s library system have administered Narcan on site forty-three times since they began stocking it five years ago.

“I think that we potentially saved forty-three peoples’ lives,” she said. “And I think that other (libraries) should think about implementing it if they’re seeing these challenges in their own community.”

Jeske notes that Denver’s program didn’t set out to solve “the whole city’s challenges,” but rather to be “one more place where this could be used if needed.”

“We knew that, given the thousands of people we see every day, that there would be people that could potentially benefit from us having this available,” Jeske said.

In Chicago, the library partnership isn’t specifically meant to address overdoses happening on site—although Richardson said it could be used in that instance as well—but rather as a means of distributing the medication in neighborhoods where it may be most needed.

Community members can come into the library branch and take the Narcan, packaged in a small box, with them. As of early March, twenty-four kits had been distributed from the initial fourteen branches, according to CDPH. The goal, of course, is to reduce the number of fatal overdoses happening in the city. It’s also about educating all community members, Richardson said.

“It’s going to be really important for all Chicagoans to understand what an opioid overdose is, what’s happening in the city and what they can do … which is to carry Narcan, to understand what Narcan is and just be aware that this is happening,” she said.

If someone is experiencing an opioid overdose, the nasal spray will revive them. If the person is not experiencing an opioid overdose, Narcan won’t be harmful.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention notes that carrying naloxone is no different than carrying an EpiPen for someone with allergies. “It simply provides an extra layer of protection for those at a higher risk for overdose,” the CDC says on its website.

“Naloxone quickly reverses an overdose by blocking the effects of opioids,” according to the CDC. “It can restore normal breathing within two to three minutes in a person whose breath has slowed, or even stopped, as a result of opioid overdose.”

The CDC also notes that signs of an overdose include: small, constricted “pinpoint pupils,” loss of consciousness, slowed breathing, choking sounds, and cold, clammy or discolored skin.

If you think someone may be overdosing, the CDC advises calling 911 immediately, administering naloxone if it’s available, trying to keep the person awake and breathing, laying the person on their side to prevent choking, and staying with the person until emergency assistance arrives.

“If we can keep people alive, when they overdose, we can get them help, we can get them treatment, and other resources,” Richardson said.

If you or a loved one is struggling with a substance use disorder and would like help, call the Illinois Helpline at 833-234-6343 or visit https://helplineil.org/app/home.

Courtney Kueppers is a Chicago-based journalist. She last wrote about food insecurity in South Shore.