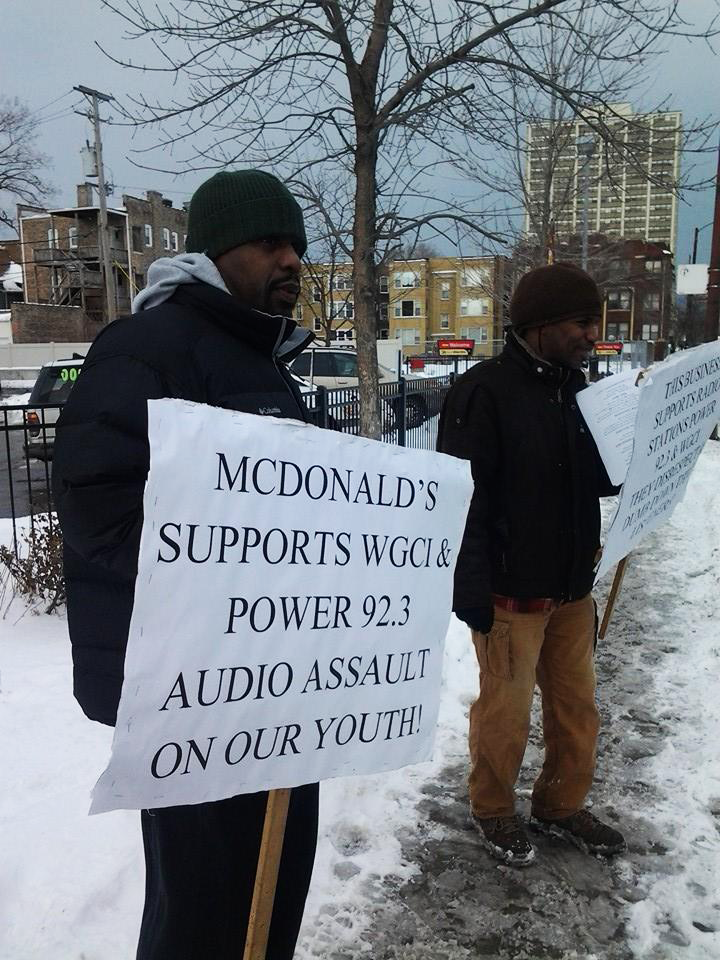

By eleven, the group has grown to five. Another man, in braids and a red rastacap, is now carrying the bullhorn and speaking into it. It’s difficult to make out what’s being said from behind the window, but by now all the signs are right-side up, including one that reads:

“MCDONALDS SUPPORTS WGCI & POWER 92.3 AUDIO ASSAULT ON OUR YOUTH!!!”

At this, one of the two cashiers working the front sighs wearily, clearly aware of what’s going on. The other is confused.

“What does that mean?”

“I don’t know,” the first replies. “They’re trying to scare people.”

Outside, the five have flyers ready for the scared and the merely curious alike. Their mission, as members of what the flyers call the “Clear the Airwaves Project,” is to “Clear The Airwaves from misogynistic, violent, disrespectful ‘musick’ from radio stations that target the YOUTH!”

“Radio Stations that target Afrikan Youth in the Chicagoland area are force-feeding our People a poisonous audio diet laced with Misogyny, Murder, Self-Hate, Stripping etc,” the flyers go on to say. “This is unacceptable and must end.”

Below, the flyers list the names and phone numbers of radio executives involved in the operations of Crawford Broadcasting’s Power 92.3 and Clear Channel’s WGCI—two of the most widely listened to contemporary urban stations in the Chicago area. They also include the numbers of executives at McDonald’s, a major advertiser on both stations.

As a small, middle-aged woman exits the McDonald’s, Kwabena Paul Pratt, the man with the rastacap, passes the bullhorn to the man in the Karakul, Dwight Taylor—whom just about everyone calls Kojo. Taylor promptly begins shouting into the bullhorn.

“MCDONALDS! YOU SHOULD BE ASHAMED OF YOURSELVES.”

The woman, startled, begins walking quickly away, but not before catching the eye of Pratt, who calls out to her.

“Hey, sister! Come and see why we’re out here!”

Disarmed, she approaches Pratt reluctantly and takes a flyer.

“If you close your eyes, you can still read the lyrics on the back of that,” he chuckles. “But that’s how bad they are. That’s the music they play on the radio for our children to hear.”

She turns the flyer over. There are censored excerpts from five hip-hop songs on the back—provided as “EXAMPLES OF THE TOXIC ‘MUSICK’ PLAYED ON THESE STATIONS AND SPONSORED BY MCDONALDS.” The most censored, and thus most asterisked selection, is, by far, an excerpt from YG’s “My N*gg*,” which is rendered on the flyer as follows:

“Runnin’ off a n**ga sh*t, my n**a I f**ked a n*ga bi*ch with my N**ga, my n**ga If a N**a talkin’ sh*t then he ain’t my n*gga My n**ga, my n**ga (My n**ga, my n*gga)

F*cked my first b*tch, passed her to my n*gg*

Hit my first lick, passed with my ni**a F**ck them other ni**as cause I’m down for my nig*as I ride for my nigg*s, fuck them other n*ggas.”

”Oh, I know,” the woman finally replies as she looks the flyer over. “I hear it all day. All day, every day.”

Warmly but intently, Pratt stands watching her settle into the expression of cautious agreement he sees a dozen times a week. Thirty or so seconds of soul searching—helped along, or at least punctuated, by Taylor’s cries into the bullhorn—routinely follow.

“It really is ridiculous,” she begins contemplatively.

“MCDONALDS! STOP ADVERTISING ON POWER 92 RADIO. AND WGCI,” shouts Taylor.

“They degrade women…”

“JUST LISTEN TO THE MUSIC BEING PLAYED.”

“Everything’s about harming other people…”

“HONK YOUR HORNS IN SUPPORT.”

“…committing crimes…”

A horn blares loudly.

“…and shooting up people. Total madness.”

Pratt nods. “I’ve got an AK on my nightstand,” he says, quoting a Lil Wayne song. “ ‘I’m spraying at these niggas like WD-40.’ Or ‘I’m gonna shoot up a guy in the car next to me before the light turns green.’ That’s unacceptable.”

The woman turns over the flyer again and shuffles a bit for warmth. It is below freezing.

“So this is why we’re out here,” Pratt continues. “We know that, when McDonald’s supports that type of music, they encourage more people to make that type of music. That’s what they hear on the radio. If I hear disrespectful music, well, I’m going to make disrespectful music. So that’s what we’re saying. We’re saying ‘McDonald’s, stop disrespecting the community.’ ”

The woman nods, says thanks, and goes to her car. It’s impossible to say whether or not she’ll make any calls or even remember the conversation the next day. Regardless, by this point members of the Clear the Airwaves Project, which is around a dozen people in total, have spent two hours every Saturday morning for the past five months—in the middle of the coldest Chicago winter in recent memory—sparking as many of these conversations as they can.

“I think this is some of the most we’ve ever had,” Taylor says, referring to the five who’ve come out to today’s demonstration. “I think the other day we had about nine, but this is great.”

Taylor and Pratt both hail from Gary, Indiana, where their involvement with local anti-violence activism—fronted by groups like Concerned Citizens Against Violence (CCAV), which Taylor founded—spurred the conversations that led to the creation of the Project. Activists in CCAV argue, as Taylor writes in his blog, that the culture and imagery of violent hip-hop “are primarily responsible for the dysfunctional status of our young people.” They began picketing outside of Power 92’s headquarters in Hammond, Indiana in 2007. Soon, they started asking the station’s most significant sponsors to pull their advertising.

Even then, McDonald’s topped the list of targeted companies. When CCAV activists began picketing at a local franchise that year, a company executive set up a meeting with Rob Jackson, then the regional marketing director for McDonald’s in Greater Chicago. Jackson, in turn, put the group in contact with ad sales executives at Crawford Broadcasting, which owns Power 92. Taylor alleges that at a two-hour meeting at Crawford’s Chicago-area headquarters, promises were made to change the station’s programming. In a letter sent to Power 92 two years later, Taylot cited a running of the song “Wasted” by Gucci Mane as evidence that this hadn’t happened.

“I’m looking for a bitch to suck this Almond Joy / Said she gotta stop sucking ’cause her jaw’s sore / Got a bitch on the couch, a bitch on the floor.”

Of Crawford’s twenty-three stations across the country, exactly two—Greater Chicago’s Power 92 and Rockford, Illinois’s WYRB—play hip-hop. All the rest, as Taylor now regularly points out to passersby at the Project’s demonstrations, broadcast gospel music and Christian and conservative talk radio. In fact, Crawford’s founder, the evangelical minister Percy Crawford, became perhaps the first Christian televangelist, in 1949, with the debut of ABC’s evangelical variety show “Youth on the March.” Crawford, who also founded the notoriously conservative Christian liberal arts college The King’s College in 1939, was so respected by the evangelical movement that the Reverend Billy Graham spoke at his funeral. The company remains entirely family owned.

“If there is one Crawford Broadcasting employee who would allow their children to listen to this song,” Dwight wrote of “Wasted” in his 2009 letter to the company, “we will discontinue our plans to have this type of music eliminated and you will never hear from us again.”

Absent a response, CCAV continued picketing Power 92 on and off for the next few years. At some point in late 2012 or early 2013, Taylor, Pratt, and a small group of others began formulating what would become the Clear the Airwaves Project, a loose organization intended to focus solely on demonstrations. At that time they also decided to push for changes at WGCI, owned by radio giant Clear Channel Communications. Last spring, the Project began a new set of demonstrations at a Chicago-area location of the Menards hardware chain, another advertiser on both stations.

Menards pulled their advertising from Power 92 within weeks, while maintaining their buys at Clear Channel. Emboldened by the partial victory, the Project’s activists again set their sights on McDonald’s, and chose to fix their demonstrations upon the franchise at Stony Island and Marquette for its symbolic significance—the location became the first black-owned and operated McDonald’s in 1968, when it was franchised to Herman Petty, the late, black businessman. Petty would go on to found the National Black McDonald’s Operators Association (NBMOA), an organization intended to assist and represent the interests of black McDonald’s owners throughout the country. Today, Petty’s achievement is commemorated with a plaque and a sign outside the location, as well as an artistic timeline of the Association’s history inside. According to the Association’s website, the organization represents “the most successful group of African-American entrepreneurs in the U.S. today.” By choosing to stage their demonstrations at the Stony and Marquette location, the Project both invokes and challenges the Association’s clout and legacy. In a statement on the Project’s protests, the association wrote that “the McDonald’s Owner Operators of Chicagoland and Northwest Indiana have a long history of commitment to the communities in which we serve.” “We also support our marketing decisions,” they go on to say, “and in this case, we are appropriately communicating with our various adult customers through the local channels.”

“They of all people should know better than to support what they’re supporting,” Taylor tells me in a conversational tone far more mild than his shouting into the bullhorn would suggest. “They have much power. That’s why we’re out here.”

In December, the Project’s demonstrations and the calls and emails incited by its flyers and active Facebook page led to a meeting with Clear Channel representatives downtown. Once again, Taylor found himself in a room for a two-hour meeting with radio executives, including Clear Channel’s head of programming for the Chicago area. But this time, he tried to make his case differently.

“We took them in the programming room and it turned out that they’d never really listened to the music and the lyrics,” he tells me.

“I don’t think it was embarrassing. That’s what’s sad. At the end, we felt like the meeting was just a big game to them. Because when we took them down there and they’d never listened to the programming—I mean bit by bit, you can hear the foul language, the disrespect—they said they felt that they weren’t going to change it because ‘this is what the country wants.’ ”

He quotes the executive in a tone that suggests the listener is supposed to find the statement—and the notion that a radio station could be bound or beholden to consumer preference—plainly nonsensical. And for the Project, many things are plain. The MLK Day demonstration came at the peak of a winter that saw articles and documentaries on the link between hip-hop and violence in “Chiraq” approach a ubiquity akin to the omnipresence of McDonald’s locations.

Central to debates on the topic is the question of whether the violent and misogynistic music of people like Gucci Mane or local drill-music star and think-`piece generator Chief Keef actually leads to violence and misogyny. Many have argued instead that the violence and misogyny in the music of artists like Keef and Mane are authentic and homegrown reflections of grim realities caused by the economic and social dysfunction of troubled communities like Keef’s section of Englewood or Gucci Mane’s section of Atlanta. Those who argue this essentially contend that real-life violence and misogyny in communities influences hip-hop far more than violent and misogynistic hip-hop influences communities. The Project strongly disagrees.

“Music is a huge influence,” Teri Delk, another regular at the Project’s demonstrations, tells me. “Throughout our history music has had a huge impact—going way back to Africa—on the way we communicate with each other. It’s part of how we gained freedom from slavery—the communication of routes we needed to take. Music is huge in our culture. So you can’t dismiss it as, ‘Oh, well it’s just music.’ ”

“I’ve come up in an era when I’ve seen the change in hip-hop,” she continues. “In the eighties we had the Afrocentric hip-hop music. When I was a teenager and I heard KRS-One tell me about my roots in Africa, that made me want to learn my history and say, ‘Well, what is he talking about?’ But when violent rap came about, we started seeing more and more murders. The Bloods and the Crips in LA started sparking up. We’ve seen the influence of the switch from conscious music to gangsta rap reflected in our children.”

“I look at the artists as being pawns, just like our kids,” adds Bernard Creamer, another core Project member. “I don’t blame the artists. Look at Chief Keef as an example. Chief Keef is, what? A sixteen, seventeen-year-old boy? [Keef turned eighteen in August.] He’s relatively poor, grew up in Englewood, didn’t have much. If somebody’s telling you, ‘I’ll give you millions of dollars to talk about the kind of stuff you’re talking about on YouTube, and make cheap music on your Macbook’—I mean, that’s what it is. He’s going to take that money. It’s quite clear. The labels know what they’re doing.”

This is the Project’s worldview—that predatory and probably racist labels and corporations push gang culture, drug culture, and misogyny on black youth for profit. If it weren’t for their support, they argue, songs like Spenzo’s “Wife Er,” whose hook Pratt recites multiple times every Saturday (“I can never wife her / Only one night her / Women full of lies / I just fuck ‘em then pass ‘em to my guys”) would only be listened to by a degenerate few, if written at all. For however organically generated from harsh, lived experiences this kind of hip-hop—which Pratt is fond of calling “slop-hop”—might be, responsibility for its popularity and wide influence, they contend, is borne by companies led by powerful people for whom the described lifestyles are completely foreign—people that, as Taylor wrote, almost certainly shield their own children from such influences.

And at its core, the Project really is about children. As easy as it might be to construct a defense of “slop-hop” on the grounds of artistic freedom, or the empowerment its lyrics can provide, or its value as simple entertainment, it is considerably more difficult to articulate such defenses to a woman who has spent two often-snowy, often-windy, and always cold hours every week for the past several months at a demonstration because she doesn’t understand why, as Delk tells me quietly, her daughter has to live under the influence of music that insists she, as a young black girl, is disposable.

It is difficult to tell Delk that her fear of what men who listen to such music might do to her daughter while she’s away at college is unjustified, or to tell Taylor that his contempt for the music that soundtracked the lifestyle of those who accidentally killed thirteen-month-old Josiah Shaw in 2008—an event that CCAV memorializes every year with Shaw’s family—is misplaced.

And it is very difficult to tell Pratt that he might be wasting his time.

“I’m tired of coming out here,” he says to me with a weary shake of his head. “We’ve got other stuff going on. But we know our children are being affected by this ignorance.”

When I tell him on MLK day that I’ll be coming out to cover the protests for the next few weeks, he chuckles.

“Hopefully not,” he laughs. “Hopefully soon, they pull their ads and we won’t have to be out here no more.”

That was three months ago. The Project, as of today, has yet to receive any new responses from McDonald’s, Clear Channel, Crawford Broadcasting, or Power 92 and WGCI themselves. Since the protest on January 20, the group has staged a demonstration almost every week, often doing battle with both the particularly nasty winter—on a couple of occasions in March, the group had to cut its demonstrations outside of the largely empty McDonald’s short, on account of bone-chilling temperatures—and skepticism.

“It ain’t going nowhere, man,” a sympathetic man tells Pratt, ruefully, the week after the MLK Day protest. “’Cause these kids ain’t listening, man! They’re not listening to us or you.”

“But what are we going to do?” Pratt shoots back. “We can’t just sit there. We’ve got to fight it.”

“You know, it’s just like someone told me the other day,” the man replies, shaking his head. “He was saying to me, ‘We need more leaders.’ And I was like, ‘Look man, we’ve had enough leaders. What we need are better followers.’ ”

“Now it’s all in the youth’s hands,” he continues. “You can’t expect a fifty- or sixty-year-old man to continue the struggle. And if young people like that music with all the sex and the killing…”

“But we can stop it though!” Pratt interrupts. “That’s why we’re out here, brother! Come out next Saturday—and tell your son to come out here with us next Saturday.”

Slowly, and thoughtfully, the man takes a flyer.

“Well, I’m off on Saturdays, so…I can definitely do it.

This is how it goes. On a good day, the group will squeeze half a handful of promises like this one from passersby—most of whom will never show up—and get a few honks of assent from passing traffic. The group is often buoyant, trading jokes about the absurdity of some of the lyrics they’ve heard recently and Taylor’s often-broken bullhorn. They act like a tight-knit group of friends, which one would suppose they’d be: they’ve spent their early Saturdays together for the better part of the past year. And everyone who passes—the drivers who glare at them coming out of the drive-through, those who obviously take flyers only to be polite, and the often impassive or wisecracking kids who walk by blasting some of the very music they’re fighting through their headphones—is a “brother” or a “sister.”

On more sparsely attended days during the winter, Pratt, Taylor, and the others would commonly tell passersby that the group would grow in size as the weather improved.

“Obviously, the more the merrier,” Bernard Creamer says optimistically on a particularly cold Saturday. “Hopefully it’ll warm up soon and we’ll have people come out.”

Temperatures this past Saturday reached a high of sixty-four degrees. It was a clear day. In his usual position out in front of the drive-through, Pratt stood alone.

“First a song about killing people. Then a song about guns. Then a song about drugs. Then a song disrespecting our women. Back to back to back to back. And McDonald’s gives money to these poisonous radio stations. Shame on you McDonald’s!”

The words are spoken rather than shouted through the bullhorn. In between bursts of speech Pratt paces slowly around the perimeter, seeming spent.

“I mean…recall the Rush Limbaugh thing,” he says to me in frustration. “He disrespected Sandra Fluke. Pretty much immediately, thirteen companies pulled their commercials. Thirteen. And these stations disrespect our women on a 24/7 basis. And what are we doing?” He pauses.

“I’m tired, man,” he says to me finally.

As I go, he spots a group of kids, perhaps in middle school, on their way to a basketball court across the street.

“Hey brothers,” he calls out with a burst of energy. “Come see why I’m out here!”

Intrigued, they approach him. Magnetic as ever, he strikes up a conversation. From a distance, what he says can’t be heard, but it’s easy to imagine his pitch: about their music, about respecting their brothers and sisters, about their futures. They seem itching to go throughout, but several take flyers at the end before walking away.

For a while, Pratt watches them go. Then he turns the bullhorn back on.

“MCDONALD’S…”

Editor’s Note: Clear Channel Communications, Crawford Broadcasting, Power 92, and WGCI did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

The Clear the Airwaves Project is at the threshold of victory. Our presence will continue at 66th & Stony every Saturday morning at 10:30 until there is change in the programming at Power 92.3 & WGCI 107.5 radio stations.

There must be change in the programming or McDonald’s MUST pull their advertisements on Power 92.3 & WGCI 107.5 radio stations.

Forget the radio stations and forget Maccas.

You need to start at the source of this pathetic so called

music that it is nothing but pure shit.

You need to eliminate the writers and performers of this

rubbish.

Even after this important article outlining our struggle to expose and end this attack on our culture, we have yet to hear from mcdonalds corporate. In the meantime these radio stations continue to play violent obscene music. And by the way, a 20 year old was shot and killed last thursday at a mcdonalds in Gary! He iis the third young Afrikan murdered at or adjacent to a mcdonalds since this campaign began 9 months ago. We have to protect our children!

I realize this article is over 3 years, but I just discovered it and the writings of Osita. That’s how I found this article, because I’m going back an reading stuff Osita has written in the past. Let me say, I’m a 60+ year old white dude from the South and I agree with y’all 100% about the violent misogynistic music played today. I’m also not a fan of the jingoistic fake patriotic songs that get air time on country stations (and we’re over loaded with country stations down here). I’ll stick to my blues and jazz. If someone from the group does perchance read this, even though it’s been so long since the article’s original publication, I do have a suggestion. Maybe y’all are going about this wrong. It may have already been tried, but if the FCC got so worked up over an accidental flash of a boob during the Super Bowl, why would they allow intentional profanity and sexually explicit lyrics over the public airwaves? Aren’t the CDs labeled and children under 17 or 18 can’t buy them? Why then can a 6 or 7 year old turn on the radio and hear the very same lyrics? Just thinking it might be another path to take. Good luck.