Every March, cloud-like swarms of monarch butterflies leave Michoacán, Mexico, to travel north.

Chasing spring and summer’s rising temperatures towards the United States, the mass migration spans half a year, thousands of miles, and generations of butterflies.

The monarch is the national butterfly of Mexico and nine US states. Among these is Illinois, where thousands of monarchs settle in the last warm days of August.

On one of the first genuine days of Chicago’s elusive spring, around the beginning of the monarch migration, Victoria Thurmond met me in the Mary Zepeda Native Garden in Pilsen, one of many community gardens that serve as a planting and learning space for Pueblo Semilla.

Pueblo Semilla, a community-driven seed library and learning group, was started three years ago by Thurmond and Veronica Buitron while they were students at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Buitron has since graduated and moved back to her home country of Ecuador, but Thurmond, now a fourth-year student, continues to work with Pueblo Semilla as it expands to include more members and projects.

The garden is a simple and pristine space squeezed between two brick apartment buildings in northern Pilsen. Its murals, painted by Hector Duarte, a Pilsen based Mexican-American artist, feature monarchs in flight. Students from nearby school El Hogar del Niño painted each of the orange butterflies’ wings individually. The garden serves as both a plant-raising learning center and a playground for the school.

“Pilsen is a very dense neighborhood, and there aren’t a lot of green spaces,” Thurmond explained, sitting on a small hill in the middle of the garden. She held a large, worn, dark green suitcase: Pueblo Semilla’s mobile library.

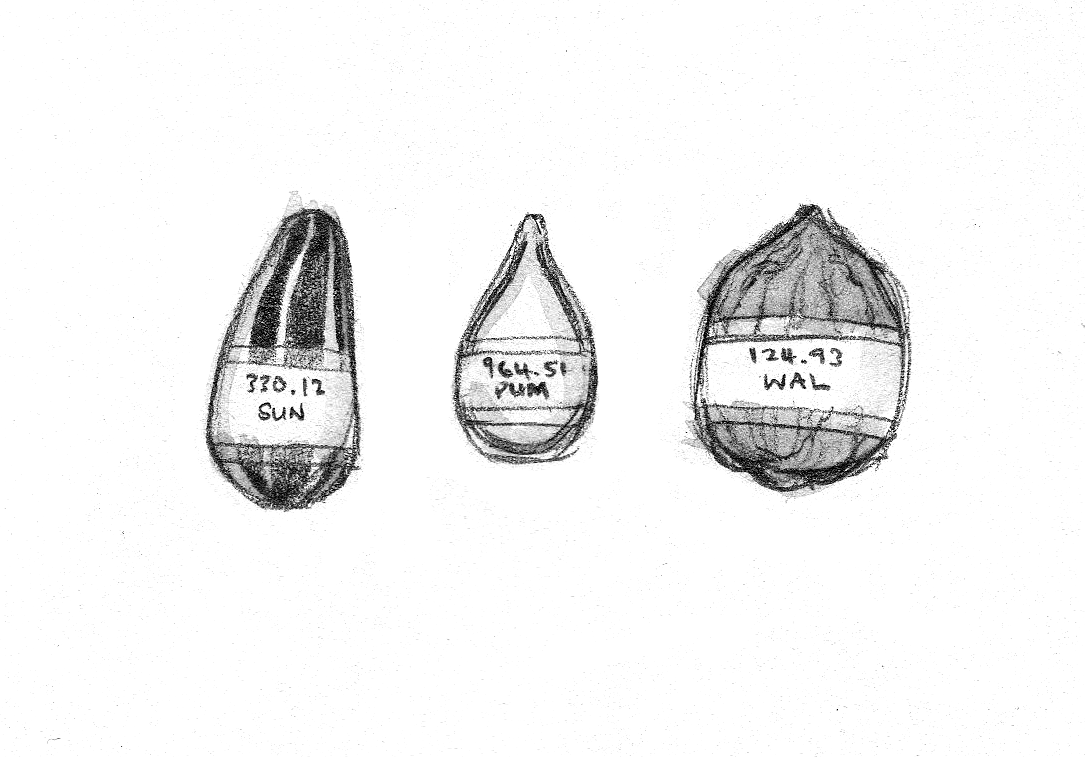

Thurmond opened and sifted through the contents of the suitcase: seeds of different native Chicago plants, seed-growing instruction booklets, checkout tabs, small glass enclosures with growing plants, and miscellaneous paperwork. The library is a completely mobile network of seeds, constantly on the move. Sometimes it travels door-to-door, lending out seeds directly to patrons.

Seed borrowing through Pueblo Semilla is seasonal, and each planter gets a handmade booklet with two pouches. Whether planting indoors or outdoors, in patios or in apartments, Pueblo Semilla patrons check out and grow their seeds over the course of one season. At the end of each season, they are expected to cultivate new seeds from their grown plants and put them in the next pouch. “With each generation the seeds become [more] local and acclimatized to the environment of Chicago,” Victoria explained. The project creates a growing library of seeds conditioned to Chicago’s harsh climate and soil, while educating residents and students at Mexican-American community schools on how to cultivate seeds locally and affordably.

The Pueblo Semilla booklet, printed in both English and Spanish, includes stories, sketches, and detailed growing instructions. There’s also a map of the neighborhood with various areas marked as either planting spaces or toxic sites; Thurmond is part of the Pilsen Environmental Rights and Reform Organization (PERRO). On the booklet’s cover is Pueblo Semilla’s logo: an open palm holding a milkweed seed.

The milkweed seed is a recurring symbol for the group. Monarch butterfly larvae feed exclusively on the milkweed plant, so milkweeds are essential to the success of the monarch migration through the United States. However, over the last few years, the gradual disappearance of the plant, due to more efficient cropping mechanisms and changes in temperature, has put the monarchs at risk. Monarch populations have been decreasing at alarming rates.

After leaving the garden, Thurmond led me on a tour of the other gardens and projects Pueblo Semilla is affiliated with in Pilsen. “[Pilsen has] changed a lot just over the last three years,” she said. “Half of the businesses on 18th Street have opened over the last year.” Thurmond was concerned about her own role in this change, too. “People are starting to have to move away with rent rising. It sucks to feel somewhat a part of that process.”

However, Pueblo Semilla works in opposition to this displacement. By bringing together Pilsen residents and working with other organizations to create and promote green community spaces, Pueblo Semilla is helping to make a more united and rooted Pilsen. New parks such as La Huerta Roots & Rays, which is slated to feature cultivating beds, picnic tables, lounging gardens, and a playground, will serve the community with the goal of helping residents become more connected and rooted.

As we sat in the Mary Zepeda Garden, Thurmond handed me a milkweed seed. Light brown and the size of a fist, the hard-shelled seed had an opening down its side like the seam of an oyster. Tufts of soft white feathers peeked through, each connected to individual seeds waiting to be blown away and settle into new ground.

The Pueblo Semilla booklet contains a tale about a party held by the milkweed for the monarchs as the butterflies arrive each year. The story ends with an instruction: “Grab a handful of milkweed silk in your hand and gaze down at it. You might feel like a space giant holding a handful of stars…Launch a handful of silken stars to drift down a Pilsen sidewalk and dream of next year’s butterflies.”

I would like to plant milkweeds in my yard too.

How do I get access to the milkweed seeds and make a donation to the cause?