Cordelia is one of the narrators featured in the digital exhibition “I’m Still Surviving: A Living Women’s History of HIV/AIDS.” The exhibit presents the oral histories of women living with HIV/AIDS in Chicago, Brooklyn, and Durham. These oral histories were created using a participatory framework in which the women narrators interviewed one another, discussed the fullness of their lives before and after their HIV diagnoses, and highlighted the resources and relationships that allowed them to survive and build healthy worlds both within and beyond the medical system. The following is Cordelia’s life story as told to Mae, a fellow participant in “I’m Still Surviving,” as well as the project director Jennie Brier. In order to respect their privacy, we are only publishing the participants’ first names.

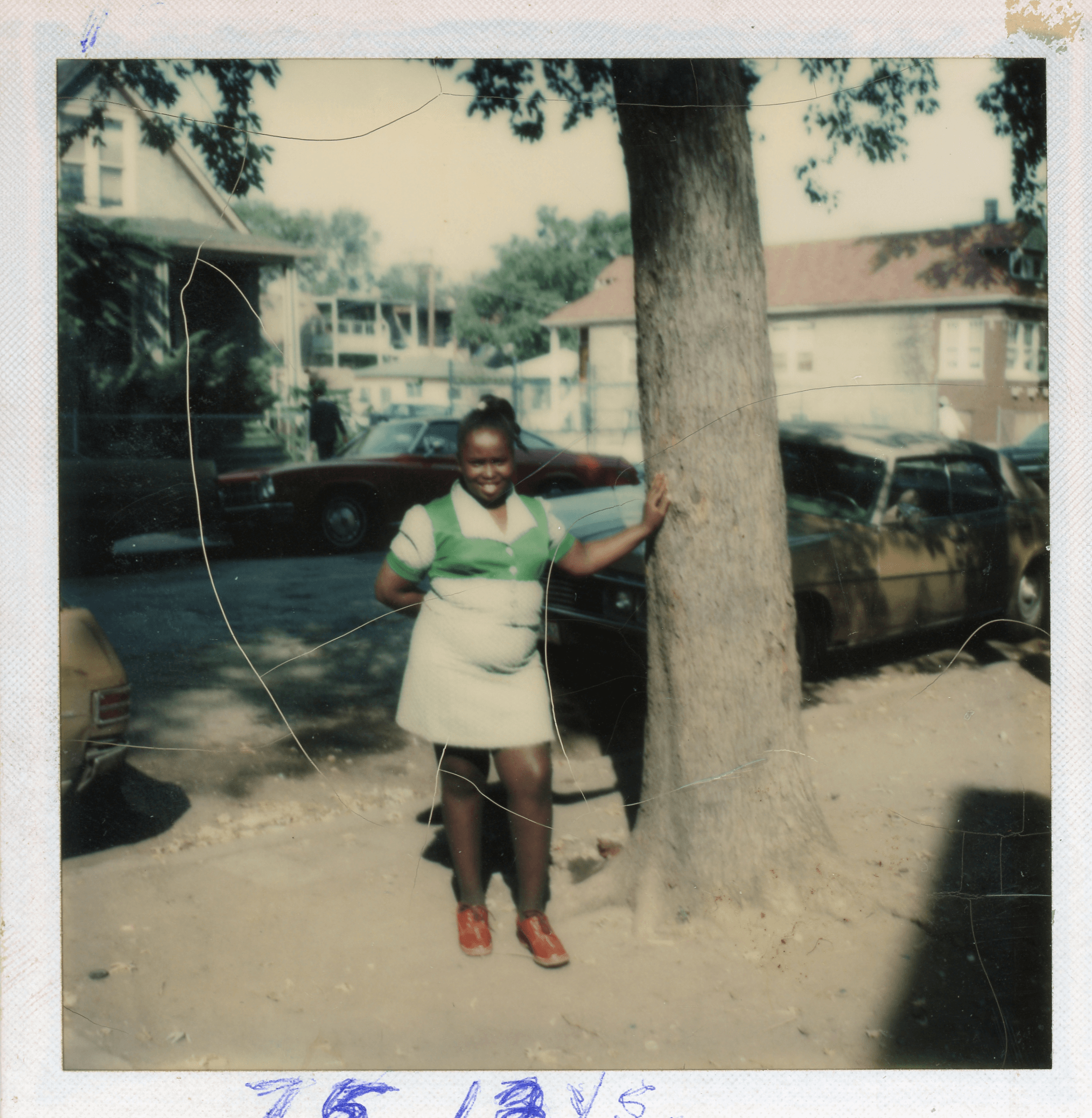

I am from a family of seven children—born and raised in Englewood, we’re still in the same house. And actually I was born in our home, that was when they had midwives. So I was born right there at South Peoria.

Before I was born, my other siblings and them used to live in the projects, in the Henry Horners. From what they say, they had fun. Only thing was they better not take their butt across Cicero. Black folks could not cross Cicero. And then [my Dad] saved his money, enough to buy a home for his kids. At that time [Englewood] was a nice area, and it was just starting to be kind of mixed where you had some white and some black. That was in ’63. Everything was fine—all of us went to school together, it was no segregation or nothing.

My parents provided for all seven of us to go to grammar school, they put us through high school, they put all of us through college. My dad, you know, he was always a good provider. He put in an application at—back then it was called People’s Light and Gas and Coke [sic]. He started off the lowest man on the totem pole, worked his way up to digging to foreman to driving the truck. And he retired from there. My mom worked for a factory. He really didn’t want her to work at all, he wanted her to just stay home and take care of the children. But she wanted to have—as she called it—a sinkhole, meaning not having to depend on my husband’s money.

My mom and dad were both from Mississippi and so they were kinda old-fashioned. They didn’t believe in children out of wedlock at all, okay? And they didn’t believe in us dating until we were sixteen years old. But of course, me being the baby and a spoiled brat of the six girls, I was sneakin’ around anyway. Around eighteen or nineteen, all of my siblings were away at school or this or that, and I was the last kid at home. And that kind of made me start wanting to venture out and be that fast little girl, you know, live the fast life.

I was dating a guy that was like twenty-five years older than me. Actually, he was my church’s organist. We were brought up in the church—me and all the girls were always in the choir. I ended up getting pregnant in ’82, which was the year that I was gonna graduate. I didn’t want to go across that stage with a big stomach and especially trying to keep up the reputation of my family and the religion, so I secretly went and had a “D&C.” They weren’t really calling it abortion back then. After that, the same guy turned me on to drugs and I started using cocaine with him. We were dating and he was doing whatever he wanted to do—long as he gave me some drugs, I was fine.

I would go back home, go back to my dad’s and mom’s—they basically provided for me, so I was never a street worker, I never had to get out there like that. And when I did graduate from high school, I went straight into working. I always have had good jobs. I was doing good things but bad things at the same time. That’s how I lost [my jobs], because of the drugs. I would be tired and call in—“I can’t come today”—and it just took a toll on me.

And then in 1992, it was around the time when Magic Johnson got diagnosed [with HIV], and everyone was kind of running to the little neighborhood clinics. And I went to the clinic in Englewood because I knew I had been sleeping with a couple different people. They told me that I had HIV, gonorrhea, syphilis, and herpes. I just was like, “You gotta be kidding me!” And then people started calling those things a package, you know, like a package deal. And I’m saying to myself, “Wow, I really got that package.”

So then I felt like life was over; I ain’t never going to be able to have no kids. I got real discouraged because I love children, I love my nieces and nephews. At that point, I felt like I didn’t have no reason to live. I didn’t know that eventually all those things—some of them—could be totally treated and I would never see them again. And some would be treatable where I could live with them. Before I found out all that, I actually was doing everything I to die…and wouldn’t die. It seemed like the more I tried to die, the more I lived. God had another plan for me.

I’m like, “Okay, you still around for something.” So I started going to the women’s support group at Cook County Hospital. And we used to sit in that Radiation Center. It would be hot as a firecracker in there because there wasn’t no air conditioner, so we’d have a fan on and we sitting this close together, and we be sweating and we just be talking. It was just one big family. Because that’s all we had. We had this little one group where we could get together and love on each other and feel, “Oh, I’m not in this by myself.”

Then they created the CORE Center. [Established in 1998 as a partnership between Cook County Hospital and Rush University, the Ruth M. Rothstein CORE Center is one of the largest HIV/AIDS clinics in the country.] So I could go to a recovery group, I can go to a Women of Dignity group, I can go to an HIV support group. I can do all of that at the CORE Center. And I could see my primary doctor. The meetings and the groups worked for me. I realized that I didn’t have to be trying to kill myself.

From day one I told my mother [that I was HIV positive]. Oh my God, you could tell her anything. She was like, “Well, Sister” (that’s my nickname, Sister). “No use in keeping it a secret; it’s something you gotta live with now. You should just tell the rest of them, they’ll be understanding.” And me knowing the type of family and sisters that I had, I knew that they would handle a problem. If anything, they would be catering to me. I told them and that’s exactly what it was. Still ‘til today they’ll say, “Sister, what’s your cell count?” Because now they are more aware about it, especially with one of my sisters being a doctor.

‘Til today, I’m surviving and enjoying life. I got clean in 2011. I relapsed in about August of 2012, and I needed my sister the doctor to read me the riot act. And my dad is now ninety-three years old so I’m his caretaker two days out the week. I looked at daddy like, well, “If I can’t take care of my own self, how the hell am I’m going to take care of you? So I’ve been all good ever since then, I’ve been good.”

My family is everything to me, they mean everything to me. It’s almost like a big party [at our house], because everybody’s got a car. There’s a big church across from our house, and a lot of people—when they pass by—they think that the church is having something. Because you see like, ten, fifteen cars out there. But it’s just our family, it’s Saturday.

The interview was recorded in 2015. Since then, Cordelia’s father has passed away. To read more oral histories of Chicago women living with HIV/AIDS, visit StillSurviving.net.

By: Cordelia as told to Mae and Jennie Brier, History Moves

History Moves is a public history project that presents underexplored aspects of Chicago’s history, led by Jennie Brier at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Its latest project is the digital exhibit “I’m Still Surviving: A Living Women’s History of HIV/AIDS.”