Nearly four months into the COVID-19 crisis, the network of shelters, isolation centers, and hotels that the city and organizations have put together to care for people experiencing homelessness has been relatively successful—though many shelter residents have contracted the virus, no one is known to have died from it. But the situation remains precarious. As the city’s designated isolation hotel fills to capacity, some people living with pre-existing conditions are stuck in shelters, where they stand at higher risk of contracting and dying from COVID-19. Others are falling through the cracks: Leah Levinger, former executive director of the Chicago Housing Initiative (CHI), told the Weekly she had met a man who was diagnosed with COVID-19, denied entrance to shelters on lockdown, and was not offered a placement in the city’s hotel, nor the isolated COVID shelters. According to Julie Dworkin, director of policy at the Chicago Coalition for the Homeless (CCH), elderly people and others with medical conditions isolating in downtown hotel units are not in any position to return to congregate settings.

Now, this patchwork of support services is poised to receive a new influx of residents needing homes as the crisis continues. As temporary protections for Chicago renters begin to expire while the pandemic and related recession rage on, many signs indicate that there will likely be a national eviction surge and therefore a surge in homelessness. In response to this situation, advocates like Levinger and Dworkin have turned their attention to one resource close at hand: the Chicago Housing Authority (CHA). Levinger and Dworkin have been in talks with the CHA since April, pushing the CHA to house people experiencing homelessness in its vacant units, given the health risks posed by living in congregate settings. But the agency’s complicated bureaucracy and its inconsistent information about available units, as well as a lax federal regulatory apparatus, have thus far hampered efforts to ensure as many people are housed as possible.

Unlike other city agencies, the CHA is still in robust financial health, and may have 1,250 vacant units in its portfolio, according to Levinger’s interpretation of an April report of their units that she received via Freedom of Information Act Request (FOIA). But after weeks of discussion, both Levinger and Dworkin said the agency has been slow to provide answers and clarity regarding their demands. To increase pressures on the agency, both are working on an ordinance to be proposed in City Council which would require that twenty percent of vacant, habitable units be given to people experiencing homelessness. Their hope is to introduce the ordinance in July, with 29th Ward Alderman Chris Taliaferro serving as the lead sponsor.

In a statement to the Weekly, Molly Sullivan, a media representative for the CHA, contested Levinger’s 1,250 vacancies figure. She claimed that the CHA actually has “more families approved for housing than we have available units,” with “193 families who are waiting for units to move in and another 590 families approved for housing who need a unit” or, in other words, they “do not have any non-leased units.” Later, CHA media staffer Matthew Aguilar clarified that actually 590 families total had been approved for housing, and 193 of those families—rather than an additional 193 families—had been assigned to specific units. In addition to disputing Levinger’s analysis, Sullivan’s statement conflicts with an April Sun-Times report that said the CHA had 2,042 vacant units, 900 of them uninhabitable. If that figure was accurate, that would still leave 359 units, taking into account those that have already been leased or promised. But Sullivan says the Sun-Times report is incorrect and that they do not have 359 habitable, vacant, non-leased units.

Dworkin said in an email that she was surprised by the CHA’s current position, given the extensive dialog she has had with the agency about vacant units. “I’m surprised if [the CHA’s] position is that they have [no habitable vacancies], that they wouldn’t have come out with that right off the bat,” she said.

Cheryl Johnson is executive director of advocacy group People for Community Recovery and a resident of the Altgeld Gardens CHA complex on the Far South Side—which, according to Levinger’s April FOIA, has 119 “unapproved vacant units,” meaning they have remained empty for longer than federal Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) regulations allow for. Johnson said she has observed that many apartments had recently been renovated and questioned the CHA’s claim, saying “If CHA is saying that these houses are uninhabitable…how is that when you just had them renovated? That’s the ultimate question.” The CHA’s Dearborn Homes were renovated in 2012 and Lake Parc Place was fully renovated in 2004, and then partially renovated again beginning in 2013. They share between them 78 unapproved vacant units, according to the April report.

[Get the Weekly in your mailbox. Subscribe to the print edition today.]

The push to get the CHA to utilize its vacant units to house people experiencing homelessness is not new—Levinger and CHI have been pressuring the agency since 2012, after she began hearing anecdotal evidence, which she then confirmed via FOIA requests, of huge numbers of vacant units amassing within the CHA portfolio. In an effort to fill these up, CHI led years of pressure campaigns at the federal level in a bid to require higher occupancy rates through stricter regulations. But this project failed in 2016, after the U.S. Senate Appropriations Committee decided to extend the Moving to Work regulatory program into 2028, which allows the CHA to maintain a higher vacancy rate than other public housing agencies while still receiving federal funds. From there, CHI’s focus shifted to finding city government regulations to reduce CHA vacancies, a project that Levinger said also failed.

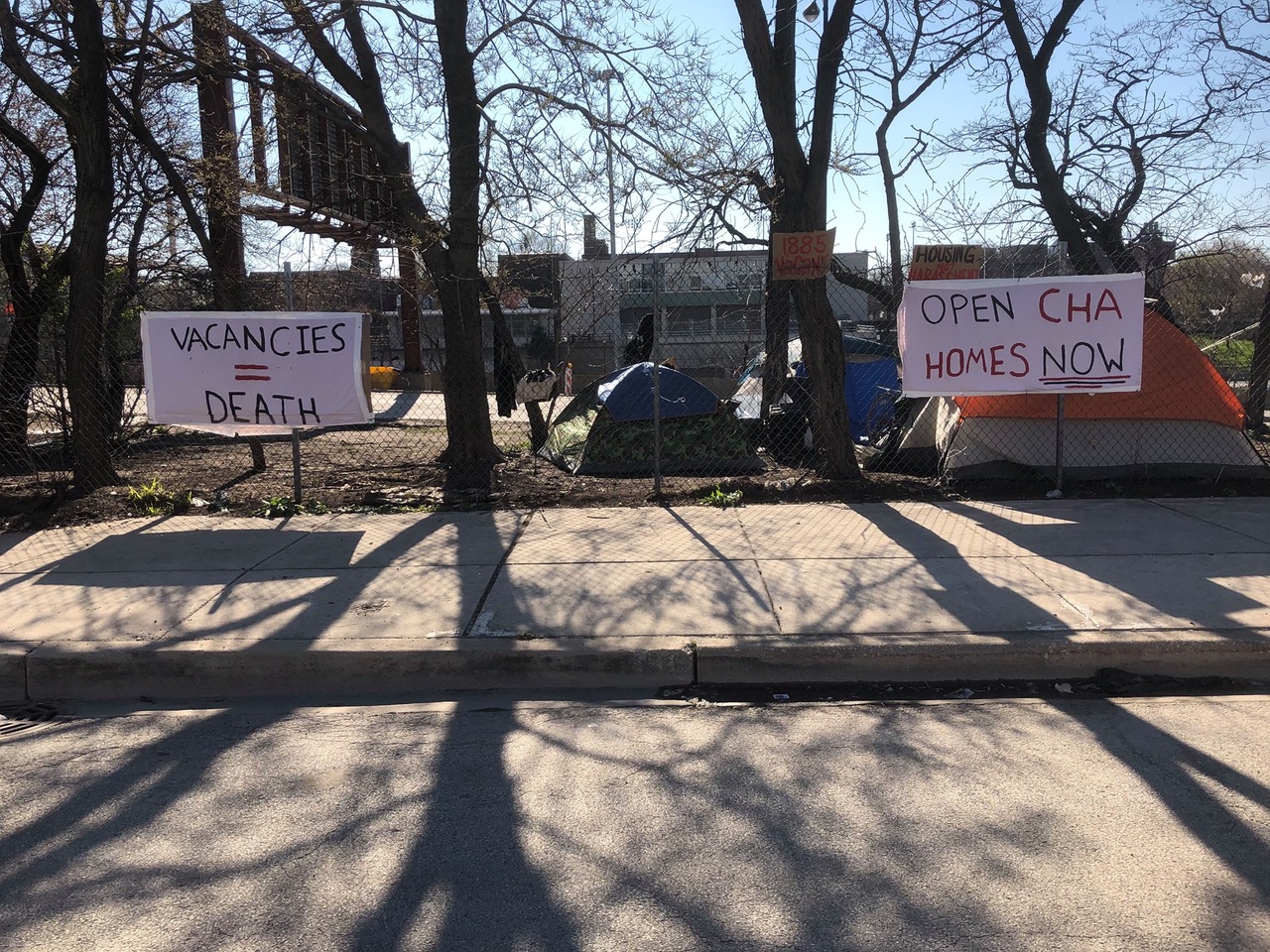

But CHI and other housing activists have not given up, and the pandemic has created renewed urgency for the cause. Posters now hang on the fence surrounding the tent city encampment on Roosevelt near the Dan Ryan Expressway, reading “VACANCY = DEATH” and “OPEN CHA HOMES NOW.” Norine “Lil Bit” Morehead, a longtime resident of the tent city, has criticized the CHA in recorded testimony posted on the Facebook page of the periodical The People’s Tribune. “How many people have to die because of housing they won’t release?” she asked.

Woodlawn resident Honni Harris is also participating in the pressure campaign. Harris has been evicted six times and has become well-acquainted with the process: asking for boxes from grocery and liquor stores when she had no money to pay for them, learning what kind of dollar store tape is strong enough to seal the boxes, calling the city to see if there was a backlog in cases that might buy her time to move, going into a shelter, getting jobs, losing jobs because of her arthritis, and finding places to stay with family, only to move again. Advocates say the system is fundamentally flawed if Harris and other Chicagoans are forced to struggle to find stable residences while available units stay empty. Harris, who has been on the CHA waitlist for six years, has given up on getting assistance from the CHA: “I’m still on the [CHA waitlist] and I don’t think I’m ever gonna be able to get it, and I’m okay with that,” she said. Her oldest son is housing her for now, but she’s hoping the CHA will act quickly to open its units for those living on the streets and in shelters.

By requiring the CHA to provide a portion of units to people experiencing homelessness, Levinger and Dworkin hope their ordinance will address shortcomings with the manner in which the CHA currently prioritizes homeless people, which, as Levinger and Dworkin found out through meetings, was not as robust as CCH had hoped. According to Levinger, instead of pushing people experiencing homelessness to the front of the waitlist, the CHA currently prioritizes people on a day-by-day basis. In other words, if you are homeless and apply on June 3, you will be pushed to the front of June 3; but if you are not homeless, and apply on June 2, you will still be processed ahead of the June 3 homeless applicant.

The ordinance would also apply monetary pressure to fill these units in a timely, complete manner, requiring the CHA to maintain a ninety-seven percent occupancy rate and a sixty-day turnaround of vacant units in order to receive city-controlled development funds. In tying funding to occupancy, the ordinance is meant to address structural flaws within the federal Moving to Work program that governs the CHA.

Housing scholar Amanda Kass studied the effects of CHA’s membership in Moving to Work in 2014, publishing a report in the Center for Tax and Budget Accountability that showed how the lax regulatory framework had led to questionable outcomes within the agency. At that time, Kass concluded that Moving to Work had enabled the CHA to routinely send out thousands fewer housing vouchers (which subsidize rent in market-rate apartments) than they could have, leaving thousands of people who needed homes without financial support. After months of poring over the CHA’s labyrinthian budgets and communicating with the agency, Kass realized that the agency had amassed an enormous reserve fund of $432 million, a huge, unspent surplus that they initially explained to her as an “accident.” It was subsequently spent on paying off pension debt early, a move she described as not in line with their mission of providing housing.

Though Kass’s scrutiny in 2014 seems to have resulted in positive changes—according to a 2017 report from the Center for Tax and Accountability, the revelation of thousands of unspent vouchers led to a sizeable increase in housing voucher spending—the CHA’s assets, in addition to its number of habitable vacancies, remain shrouded in obscurity.

In an interview, Kass explained how the current configuration of the more-than-300-page CHA bond series makes it extremely difficult to ask basic questions the public needs to know in order to effectively monitor the agency. Questions like, “How much money does the CHA currently have for building units? How many units does it plan to build this year and with how much money? How many did it actually build and with how much money?” are all difficult to ascertain given the way the CHA currently reports its budget. Funds raised from a recent bond series are posted on one page, capital spending on another, units intended to build on another, units actually built on yet another. The document requires a complicated cross-coordination of data, which in the past occupied months of Kass’s time—and Kass is a trained academic.

Levinger said the agency’s bureaucratic issues—the difficulty of ascertaining how many vacant, habitable units are available, as well as how much money is set aside each year to construct new units and how much is actually spent—make underlying social problems in Chicago even more difficult: “We have a white supremacy problem, we have a class- and race-based disregard for Black and brown people in this country. We have a housing authority that has been stripped of all regulatory oversight and accountability mechanisms. That is the perfect storm.”

Morley Musick is a writer and reporter from Chicago. He founded Mouse Magazine with friends in 2019 and posts short essays on his blog. He last wrote for the Weekly about evictions in South Shore.