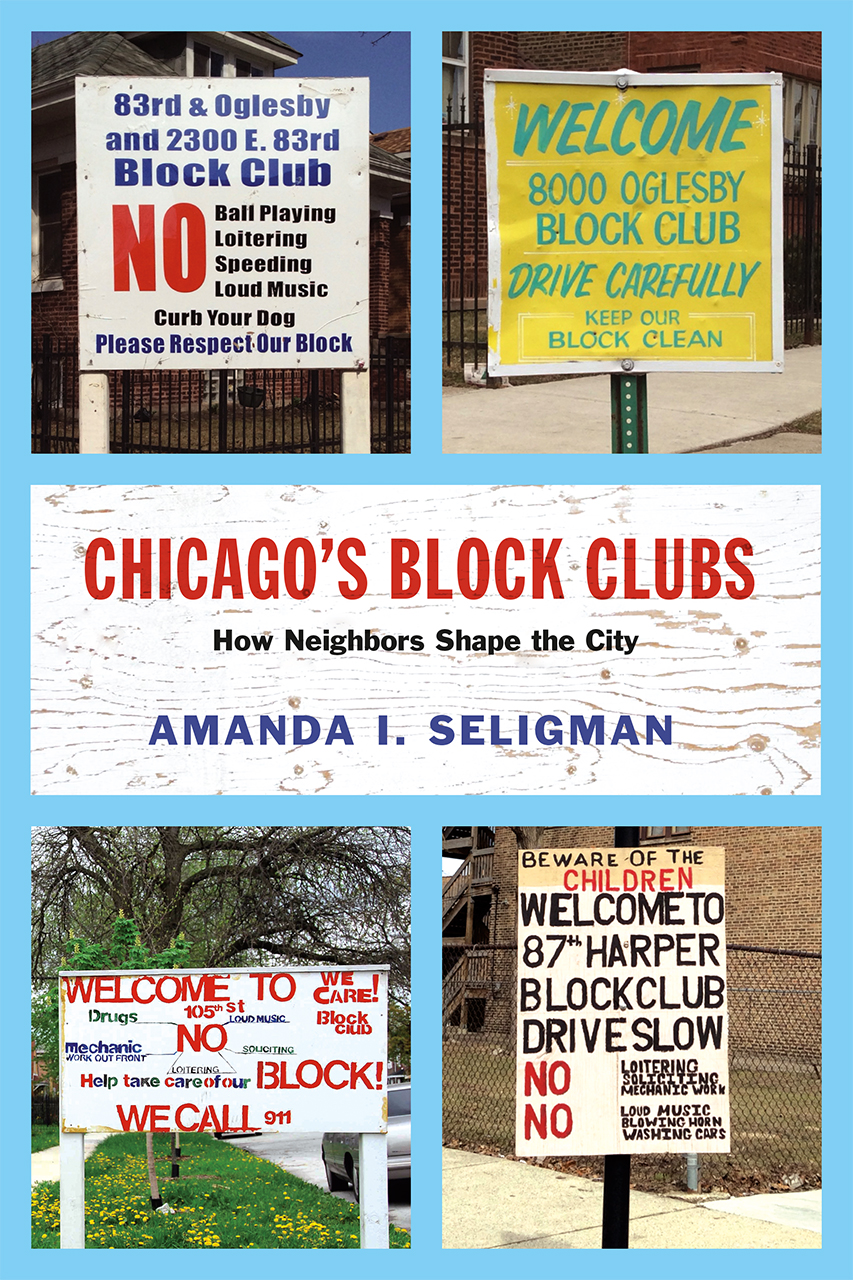

The cover of Amanda Seligman’s latest work on urban studies shows photographs of four South Side neighborhood welcome signs, the kind you immediately associate with her ostensible topic: the historically African-American block clubs of Chicago. And yet, reading the book, you can’t help but feel that the narrative of Chicago’s African-American block clubs has been omitted, a fault that Seligman explains by citing the limits of the archive she worked with while writing the book. If this was indeed the case, perhaps a sociological approach would have been better suited to her task. Her studied impassivity can be trying at times, especially to readers with inclinations toward revisionist history. That said, Seligman’s account is detailed, and helps to elucidate the relationship between Chicago’s neighborhood organizations and its city government, as well as the relationship of neighbors to each other over the last century, allowing readers familiar with the city’s history to identify ways in which Chicagoans have, at various times, worked to both oppress and uplift each other.

Seligman, a professor of history and urban studies at University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, published the book with University of Chicago Press this past September as a follow-up on material that had come up during research for her 1999 dissertation project for Northwestern University, which traced neighborhoods on Chicago’s West Side.

The introduction is promising: Seligman elucidates the origins of block clubs, started in the 1910s by the Chicago Urban League to “help black Southern migrants acclimate to the city.” On one hand, the Urban League could be characterized as a project of erasure of black Southern culture and a racial assimilation of black migrants into white culture, funded by wealthy white Chicagoans under the banner of “urban acclimatization.” On the other hand, the Urban League could be seen as an attempt by well-meaning white urbanites to welcome and assist black migrants. While Seligman herself remains neutral on the political project of the Chicago Urban League, she is perhaps strongest when she refers to the work of other historians on the subject. The most useful critique offered in her book might be that of historian Touré F. Reed: “The League’s strategy of treating organized activities as a means of improving the character of black neighborhoods was an accommodation to residential segregation…[but] Leaguers, like all of us, were products of their historical moment. They used the intellectual and institutional tools at their disposal both to understand their world and to try to create a more democratic society.” (Note to a would-be reader: if this view of the Urban League is too charitable for you, I would not, in good conscience, be able to recommend this book as an enjoyable read.)

Instead of a chronological narrative, Seligman organizes the book into six topics relating to the functions and operations of block clubs: protection, organization, connection, beautification, cleanliness, and regulation. Avoiding the broader social and political movements of her chosen period, the twentieth and early twenty-first century, Seligman instead focuses on the archives left by a handful of block clubs and neighborhood organizations, and the ways that they approached the aforementioned topics. While this methodology is useful for a discussion of the function of block clubs, which Seligman argues have been overlooked as a social structure, the approach ignores the historical influence of organizations such as the Nation of Islam, African-American churches, and the Civil Rights Era, all of which critically influenced the landscape of South Side of Chicago, and arguably had (and still have) important ramifications for residents at the neighborhood level.

Seligman focuses mostly on three neighborhood organizers, all of whom are white: Faith Rich, the secretary of 15th Place Block Club, a club within the Greater Lawndale Conservation Commission (GLCC); Julia Abrahamson, executive director of the Hyde Park-Kenwood Community Conference (HPKCC); and Father Francis X. Lawlor, a racist Catholic priest who tried to prevent integration in West Englewood through the Southwest Associated Block Clubs (SWABC) in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Organizer Saul Alinsky also gets a thorough treatment over the course of the narrative.

That said, one of the strengths of Seligman’s introduction is her insight that the contributions of women, and particularly black women, in the daily work of block clubs have been overlooked. The book is certainly a testament to women in organizing, though the glimpses of black women’s efforts and experiences are all too fleeting.

The voices of individual African Americans involved in the century long history of block clubs are expressed—with brevity compared to their white peers—by just two women: Alva B. Maxey, head of the Chicago Urban League in the 1960s, and Gloria Pughsley, who spearheaded block club organization in North Lawndale in the 1950s. Maxey, as head of the Chicago Urban League, certainly can’t be claimed as an example of grassroots organization at the neighborhood level, so we are left with the description of Pughsley as our singular voice of black neighborhood organizing. The description is problematic at best, given historic portrayals of American black women, and Seligman remains critically neutral while relaying that Pughsley was seen as angry, “difficult,” and “hostile,” as well as relating an incident in which Pughsley was ridiculed by a social service worker in a report for being overweight. While the characterizations of white block clubs’ activities and white block club members themselves are detailed, the treatment of predominantly black block clubs and their members are disturbingly brief. Though it is not difficult to imagine that nuanced writing and news coverage of black migrants in the twentieth century was sparse, the partial and white-centric history of Chicago’s block clubs that results is utterly disconcerting and goes largely unaddressed by Seligman.

That’s not to say that a history of African American block clubs at a structural level does not emerge in the work: Seligman’s analysis traces the ways in which early block clubs, organized by members of the Urban League, stressed a politics of respectability and emphasized a clean and quiet neighborhood. During World War II, the block club was implemented citywide by Mayor Edward Kelly to emphasize patriotism through support of troops, bond-buying, and cultivation of victory gardens. Block clubs shrunk again in the postwar years, and the white block clubs that remained focused on imposing racial segregation through restrictive covenants and explicitly violent acts of racism against blacks who tried to move in to white neighborhoods.

Black block clubs had their own issues: black property owners, concerned for their safety and property values, responded to the waves of poor Southern migrants that arrived during the Great Migration by imposing further restrictions on acceptable appearance and behavior, such as telling recent migrants to fight stereotypes by not loitering, or not leaning on their porches while eating watermelon. Additionally, the strain of migration manifested in the exclusion of renters, who were not seen as having a significant stake in the neighborhood, from block club organizations. Seligman points out that in both cases block clubs supported exclusionary and classist principles targeted at poor migrants.

As block clubs approach the turn of the century, the narrative shifts from anti-migrant to anti-blight and anti-crime. Seligman discusses blight as exemplified by increasing numbers of abandoned buildings and vacant lots, where dangerous and criminal activities occurred. As for crime, while Seligman doesn’t address the construction, decay, and eventual destruction of Chicago’s housing projects (causing an influx of poor black families into middle-class black neighborhoods, as discussed in a chapter of Natalie Moore’s incredible book, The South Side) or the Chicago Police Department that policed them, she does pause to provide a description of Chicago’s gangs, describing the way they menaced communities, corrupted youth, and formed large structures for organized crime. While her statements contain truth, they lack analysis of the structural conditions leading to Chicago’s gangs, and gangs are largely the only organizational structure besides block clubs attributed to Chicago’s African Americans in the section, which make her reasons for treating the topic in such a selective way seem misguided at best.

In the 1990s, in order to address increasing concerns about crime, the city again took block club organizing into institutional hands. This time it was through CPD, and specifically through a program called Chicago Alternative Policing Strategy (CAPS), which led efforts to organize neighbors for the purposes of neighborhood surveillance and reporting of suspicious or criminal activities. As Seligman points out, “the CAPS program … represents the first time the city government has tried to systemically create a partnership with Chicago’s block clubs that is responsive to resident’s daily concerns.” And it’s true that early on, the CAPS program helped to foster community-police relations and its implementation correlated with decreases in crime. But reduced funding to CAPS through the 2000s and rising mistrust in the CPD over past decades mean that the well-intended program is now a shell of its former self, a fact Seligman neglects to mention.

It is hard to miss how, again and again, the block club was used as a means of controlling black citizens, whether through the Urban League, through housing discrimination by white block clubs, or through policing. And yet this telling of the story is not the one Seligman chooses to emphasize. Instead, there’s an overabundance of minutiae: Seligman recounts how a Hyde Park club raised the funds to install lighting on an unlit street, or how another club paid one cent for every littered bottle neighborhood children brought them, or the role of holiday decorating, or the use of positive loitering in Uptown to deter crime. For Seligman, the point here is to emphasize the intermediary role the block club fills: its power is greater than the efforts of an individual citizen, but not as great as a neighborhood association, alderman, or the police. With these details, Seligman builds her argument for neighboring as an important urban relationship worthy of scholarship. While she points out that neighborhoods that look nice, thanks to the efforts of block clubs, are more pleasant to live in, there are critical issues inherent in her history of block clubs in Chicago as a whole. Her account raises complicated underlying questions: is neighboring essentially a form of surveillance and control, or a relationship of support? What is neighborhood safety and how (and against whom) does it operate? Can we envision cleanliness, beauty, and safety in ways that are not racist or classist? The answers are not provided in this book.

The conception of neighboring Seligman has outlined in Chicago’s Block Clubs is far from the borrowing-a-cup-of-sugar style. Though she does not explicitly state it, Seligman outlines a relationship of neighboring that contains seeds of classism, racism, ageism, and renter-discrimination. Despite her numerous examples of neighbors working together successfully on small-scale improvement projects, Seligman is not completely dismissive of the more divisive aspects of this complicated relationship. In her own closing words: “Neighbors do not choose each other as companions in the way that friends mutually consent to their affiliation…It is tempting to imbue the word ‘neighbor’ with a range of uplifting meanings that imply positive connection and mutual care. But neighbors do not always treat each other well…neighbors [can] be adversaries rather than allies.”

Amanda I. Seligman, Chicago’s Block Clubs: How Neighbors Shape the City. University of Chicago Press. 312 pages. $30.00.

Did you like this article? Support local journalism by donating to South Side Weekly today.