Is Fritz Kaegi a reformer? Or is he really an incompetent bungler—or worse, doing favors for the likes of Donald Trump, Mike Madigan, and mob boss Joey Lombardo—as the headlines for a recent series of Chicago Sun-Times investigations suggest?

Kaegi was elected Cook County assessor in 2018 in an upset over incumbent Joe Berrios, who also chaired the Cook County Democratic Party at the time. Berios’s assessments were shown by multiple independent analyses to be biased against low-income communities and small businesses, and Kaegi promised to fix that. So far, research shows that he has consistently brought his valuation of large commercial properties closer to market rates, which will reduce the relative tax burden on homeowners.

So it was notable when a series of investigative articles in the Sun-Times appeared to promise tales of scandal and corruption in the assessor’s office. The articles themselves focused on a small number of errors in administering property tax exemptions, most of them dating to previous administrations. It takes close attention to realize that the real story, that of a reformer striving to correct problems that have festered for years, was being obscured in a cloud of insinuation and falsely framed to make the reformer look like a hack.

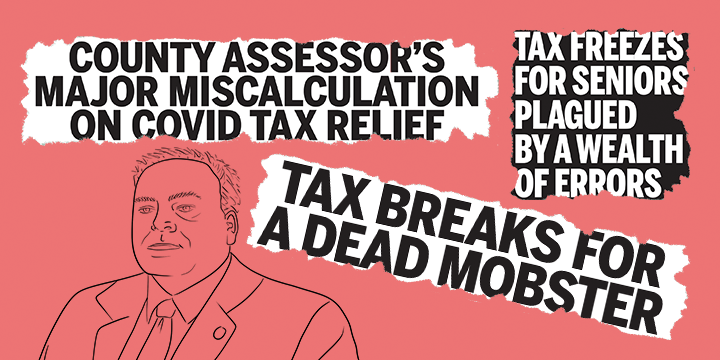

The headlines certainly blared: “Tax Program Riddled with Errors and Lax Oversight,” “Kaegi Botched COVID Tax Relief,” and “Cook County Assessors Gave Tax Breaks to a Dead Mobster.” The layouts bristled with photos of fancy homes and personal financial details that recall a gossip magazine’s survey of who makes how much.

Two separate articles last year featured pictures of a Gold Coast couple apparently chosen by Sun-Times editors to represent people who benefited from mistakes in administering a senior tax break. Both stories devoted several paragraphs to detailing the couple’s spending habits and included an old photo of the pair with big hair and loud formalwear “at a gala in the 1990s,” presenting them as the kind of rich folks that Kaegi, elected on a promise to improve equity, is really helping.

That particular exemption program, designed to shield longtime residents from the effects of gentrification on tax rates, is one of eight exemptions available to Cook County homeowners. The deeper story may be that state legislators love showering their constituents with such minor goodies, rather than addressing larger budget problems that force local school districts to carry most of the cost of public education, thus giving Illinois some of the highest property tax rates in the country. And that with 1.8 million properties to assess in Cook County, those exemptions are virtually impossible to administer with 100 percent accuracy.

But while the Sun-Times mentions the role state legislators played in creating this complicated system, the stories zero in on and amplify the significance of the small number of errors Kaegi’s office made. According to the Sun-Times, “officials admit the program is riddled with errors,” and Kaegi’s office “admits it’s made numerous errors” calculating exemptions. (Kaegi’s office took issue with that characterization in a subsequent blog post, though you wouldn’t have learned that from the Sun-Times, which repeated the framing in story after story.)

It’s not hard to visualize the TV ads using headlines from the series to attack Kaegi. And his opponents know that—they jumped right on the story. County Clerk Karen Yarbrough, a longtime Berrios supporter, attacked Kaegi over “major errors” in the program. And Kari Steele, a challenger to Kaegi who’s backed by the city’s commercial property association, cited the article when she announced her candidacy, saying, “A Sun-Times investigation revealed that [Kaegi] badly mismanaged the senior citizen tax rates program.”

The facts about the true scope of the program’s problems only trickled out long after the big splash.

The Sun-Times formulation, repeated in several stories, seemed designed to exaggerate the problem: “The Sun-Times examination of the freezes on 144,000 residential properties found the tax breaks shifted $250 million onto other property owners even though the freezes often were incorrectly calculated.”

Indeed, the assessor’s office noted in a blog post that following the story, “Some have asked whether this entire $250 million figure is money that is going to people who do not qualify.” It isn’t.

It’s only in a second editorial two weeks after the initial article—after a first editorial which said only “the dollars involved are high,” once again citing the $250 million figure—that we learn that the assessor’s office has determined “senior freezes were improperly granted using an outdated formula to no more than 0.2% of the 144,000 properties” that get the exemption. The cost of faulty exemptions to other property taxpayers? “Less than $1 and probably a lot less.”

In fact, a lot less. In its blog post, the assessor’s office wrote that of the tens of thousands of senior freezes exemptions, about 150 were incorrectly calculated. That cost average taxpayers about one or two cents on their tax bill.

Taking that analysis at face value, that’s hardly a program “riddled with errors.” And it’s quite a stretch to say the exemptions were “often” incorrectly calculated when roughly one in a thousand were erroneous—and the cost to taxpayers was virtually nil.

Subsequent stories repeated the pattern: lurid headlines and framing attacking Kaegi, and facts which don’t back up the hoopla. In September, under the headline “Trump Gets $300K Tax Break,” the paper reported that the former president got a property tax cut because Kaegi had “slashed” the assessment of vacant retail space in the Trump Tower downtown.

It wasn’t until halfway through the story that it was revealed that Trump’s tax bill is actually higher than it was under Berrios. With more diligence than a newspaper article should require, a reader could piece together the real story together from facts scattered more or less randomly through the Sun-Times piece.

What actually happened is that, in 2020, Kaegi doubled the assessed value of the vacant space, bumping Trump’s tax bill up to $1 million. Trump’s attorneys appealed the assessment but didn’t file correctly, so his appeal was rejected. Last year they appealed again, correctly this time, and his tax bill was reduced based on a valid vacancy claim.

But because Kaegi had tightened up the policy on assessing vacant retail space—a property can now receive an assessment reduction equivalent to only half its vacancy rate—Trump’s tax bill is now about $200,000 higher than three years ago.

Any way you cut it, Trump is paying more because of Kaegi’s policies—the exact opposite of the Sun-Times’ framing of the story.

In an October story, the Sun-Times contradicted its own reporting on an exemption program for disabled veterans. A four-page spread on October 3 highlighted a number of homes whose owners pay no property tax or get a reduced bill because of the exemption, suggesting that Illinois should copy other states that put an income limit on the exemption. The story explained that the program wipes out property tax bills entirely for homes below a certain value ($775,000 last year, which works out to an equalized assessed value, or EAV, of $250,000), but that even “for those whose homes are valued by the assessor’s office higher than that, the law gives disabled vets steep tax cuts.”

That last point was apparently forgotten a week later, when the headline screamed, “Kaegi is giving tax breaks to veterans on pricey homes even though they don’t qualify.” The story profiled veterans’ homes with an EAV higher than $250,000 that received the exemption and suggested Kaegi was operating in violation of the state law. At one point, the story claimed “the number of ineligible homes getting those tax breaks has shot up under Kaegi.”

That number, according to the Sun-Times, is now 126 out of over 27,000 homes getting the exemption in Cook County.

But the second story doesn’t clarify whether veterans with pricier homes don’t have to pay any property taxes or whether they just get “steep tax cuts,” which the earlier article stated was allowed under state law. In fact, the law is murky on this point. In Cook County, Kaegi has continued Berrios’s policy of granting a partial exemption covering the value of a home up to the $250,000 limit. Disabled veterans still have to pay property taxes on the value of their home over that limit. And Kaegi’s office declined to alter that policy during a pandemic.

But facts be damned, and once more we get a splashy headline that will look great in a TV ad.

Perhaps the strangest story was the “mobster” article that appeared December 19. It revolved around nine properties where owners got exemptions they weren’t supposed to, under a variety of circumstances. Considering there are nearly two million properties being assessed, this is not particularly remarkable.

The story did mention the work of Kaegi’s erroneous exemptions department—indeed, several of the exemption errors in the story were actually identified by Kaegi’s office. But the story didn’t mention the fact that under Kaegi, the number of erroneous exemptions being identified each year has nearly tripled, which means the department now pays for itself and actually saves taxpayers money.

But the framing focused on the fact that a property owned by convicted mobster Joseph Lombardo received senior exemptions for six years after he died because “someone” continued to file for them. (His daughter, who now lives there, denied that she had filed the false claims.) This gave the paper a chance to reprise some gory details of Lombardo’s crimes.

The strange thing is that it was Kaegi’s office that found the erroneous exemption on the Lombardo property and demanded back taxes. So is the story that Kaegi is giving erroneous exemptions to dead mobsters, as the Sun-Times maintained, or is it that he is taking them away?

Rounding out a six-month string of these stories, a January 30 article maintained that Kaegi’s attempt to adjust assessments to account for market changes at the onset of the COVID pandemic was a “wild miscalculation.” In fact, housing values fell in the first few months of 2021, and Kaegi decided he had to respond. But sales data wasn’t available, so he used data sets that track how unemployment rates impact property values, reducing home assessments by an average of ten percent. He also adjusted some commercial property values based on conditions in particular industries, while taking into account the fact that commercial properties had previously been under-assessed across the board.

In the following months, housing prices rebounded, as new at-home workers sought more space. But assessments are required to be based on current market conditions, not predictions of future trends. The housing market may be more or less voluble or even irrational, but assessments are a snapshot of values at a particular moment in time.

Once again, the Sun-Times ran through a set of specific properties, and again, these shed much more heat than light. They showed that the homes of Mayor Lori Lightfoot, Governor J.B. Pritzker, former Illinois House Speaker Michael Madigan, and Ald. Edward Burke all received COVID adjustments (as did all homeowners), ranging from eight to twelve percent. They also detailed how their tax bills changed, which makes us wonder what the point is. Lightfoot’s assessment went down eleven percent, but her tax bill went down by 1.4 percent, from $9,407 to $9,272. Prtizker got an eight percent reduction but his tax bill went up by over $9,000, somewhat less than two percent.

(The caption on a photo of Pritzker in the newspaper edition gets it wrong, claiming his tax bill went down, demonstrating how muddled the whole presentation is.)

These properties were contrasted with a single small home on the South Side, which got an eight percent assessment reduction, but where taxes increased by $50. The clear implication is that Kaegi is helping political insiders and screwing low-income homeowners. But, in fact, what this cherry-picked data demonstrated is that there’s no straight line from assessments to tax rates, which depend on the tax levy set by a variety of government bodies with different boundaries.

The Sun-Times also didn’t mention that taxes on the South Side home would have gone up by about $200 without the COVID adjustment, according to the assessor’s office.

Misleading headlines, contradictions with their own reporting, out-of-context overstatement of minor errors, omission of relevant facts that undercut the framing of articles—overall, the Sun-Times series is an object lesson of the need for critical consumption of media.

The impact of this coverage is hard to determine, but the headlines seem tailor-made for use in attack ads. They could certainly be fodder for the “slash and burn” independent expenditure campaign against Kaegi that downtown real estate interests are now reportedly considering. The developers and operators of luxury highrises and office towers clearly want to go back to the days when the assessor’s office gave them special treatment.

What’s less clear is why the Sun-Times would want to help them.

Curtis Black is a longtime journalist and columnist. He is also a researcher for Good Government Illinois, a political action committee founded by David Orr, which has received support from Fritz Kaegi. This is his first story for the Weekly.

This op-ed is so good that it’s loaded with factual support and can stand as a proper piece of reportage. Whatever can be said about Fritz Kaegi, there’s no argument he’s a villain.