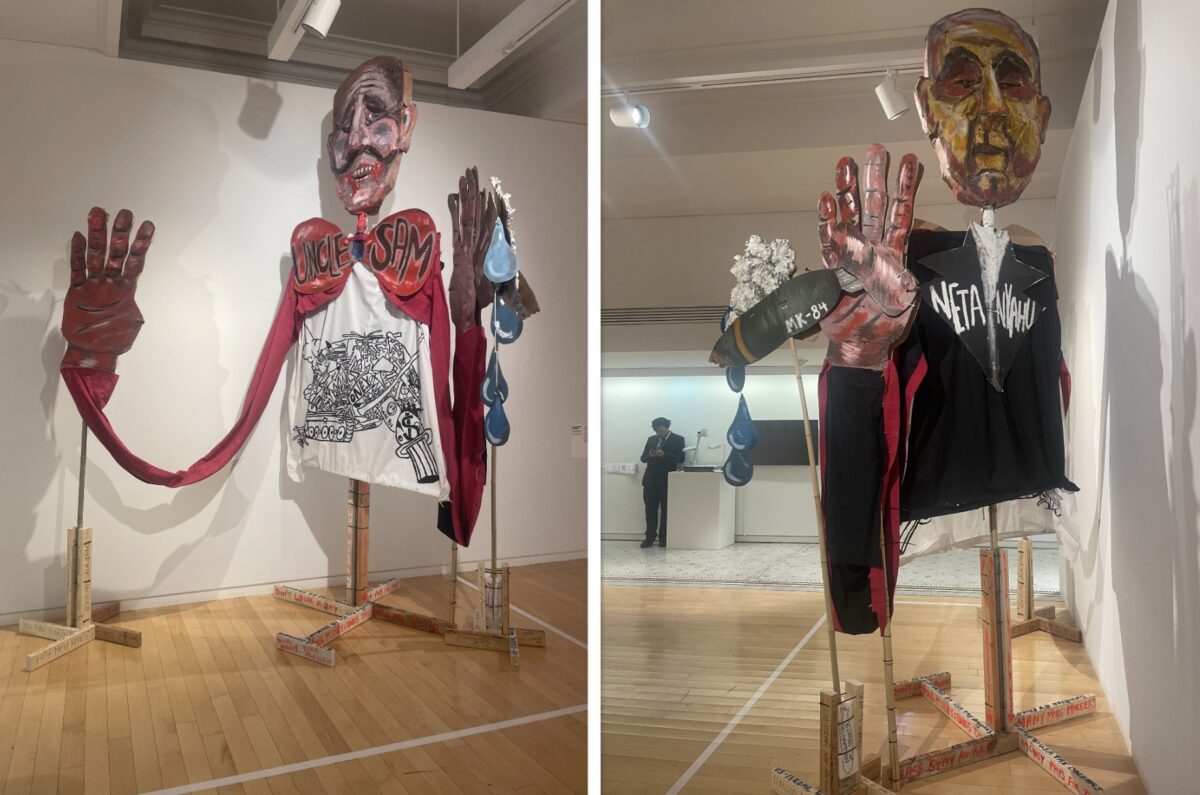

Last week, Ald. Debra Silverstein (50th Ward) led a group of twenty–seven City Council members in demanding the Chicago Cultural Center remove an art installation that they deemed “anti-American and antisemitic.” The piece in question is a large protest puppet that depicts Uncle Sam and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu back-to-back with shared, bloody hands, one of which holds a bomb. Text on the puppet’s base reads “USA-Israel war machine” and “Supported by USA tax dollars.” Silverstein, the City Council’s lone Jewish member, claimed the artwork is “unprotected hate speech” and therefore not shielded by the First Amendment.

Whether or not artwork that criticizes an Israeli head of state is anti-American or antisemitic is open to the viewer’s interpretation. But claims that its perceived offensiveness means the First Amendment does not protect the art from government interference are clearly ill-informed.

“Unprotected” hate speech was defined in the landmark 1966 decision Brandenburg v. Ohio, which concerned a Ku Klux Klan leader who’d called for violence against Jewish and Black people at a cross-burning. In that ruling, the Supreme Court held that speech is not protected when it is “directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely” to do so.

It strains credulity to imagine that the puppet at the center of this brouhaha—or any puppet, for that matter—could incite anything other than outrage. And when it comes to political art, sometimes that’s the point. (Another puppet in the exhibit depicts MOVE leader John Africa, who was killed by Philadelphia police in 1985, along with two papier-mache pig heads wearing police caps.) But simply because art may be offensive doesn’t mean elected officials can censor it.

In the 1989 decision Texas v. Johnson, the Court ruled that offensive displays are unequivocally protected speech. In the majority opinion, Justice William Brennan wrote: “If there is a bedrock principle underlying the First Amendment, it is that the government may not prohibit the expression of an idea simply because society finds the idea itself offensive or disagreeable.”

In 1994, a federal appeals court upheld that principle in a ruling the twenty-seven alders who cosigned Silverstein’s letter surely remember. That case stemmed from a 1988 incident in which then-Ald. Dorothy Tillman led a scrum of City Council members and police into the School of the Art Institute to seize a painting that depicted the late Mayor Harold Washington in lingerie. The student who painted it sued, and the City was forced to settle for $95,000 (about $200,000 in today’s money).

The alders demanding the “USA-Israel War Machine” puppet’s removal might be justified in taking personal offense at its message and conveyance thereof, just as Tillman and her comrades may have been nearly four decades ago. But like Tillman, they are sorely mistaken if they believe it’s their duty—or right—to stifle such expression. Amid a rising tide of fascism led by a president who is already making Chicago “ground zero” for his authoritarian plans, the City Council members would do well to remember their oaths to uphold the Constitutional principles that protect a free and open society.