It’s a Saturday morning in the early 1970s and two sisters just want to watch cartoons. But their mom, grandmother, and aunt are discussing their dreams. Between sips of coffee and bites of Necco Wafers, the women pore over barely held-together numerology books. Their hope is to convert their dreams into numbers and those numbers into luck for the next time they play policy, the “not-so-legal precursor to the lottery” popular among Black communities. The game “was creed to the women” in her house. So, as the older women monopolized the living room with the tv, the sisters had to wait.

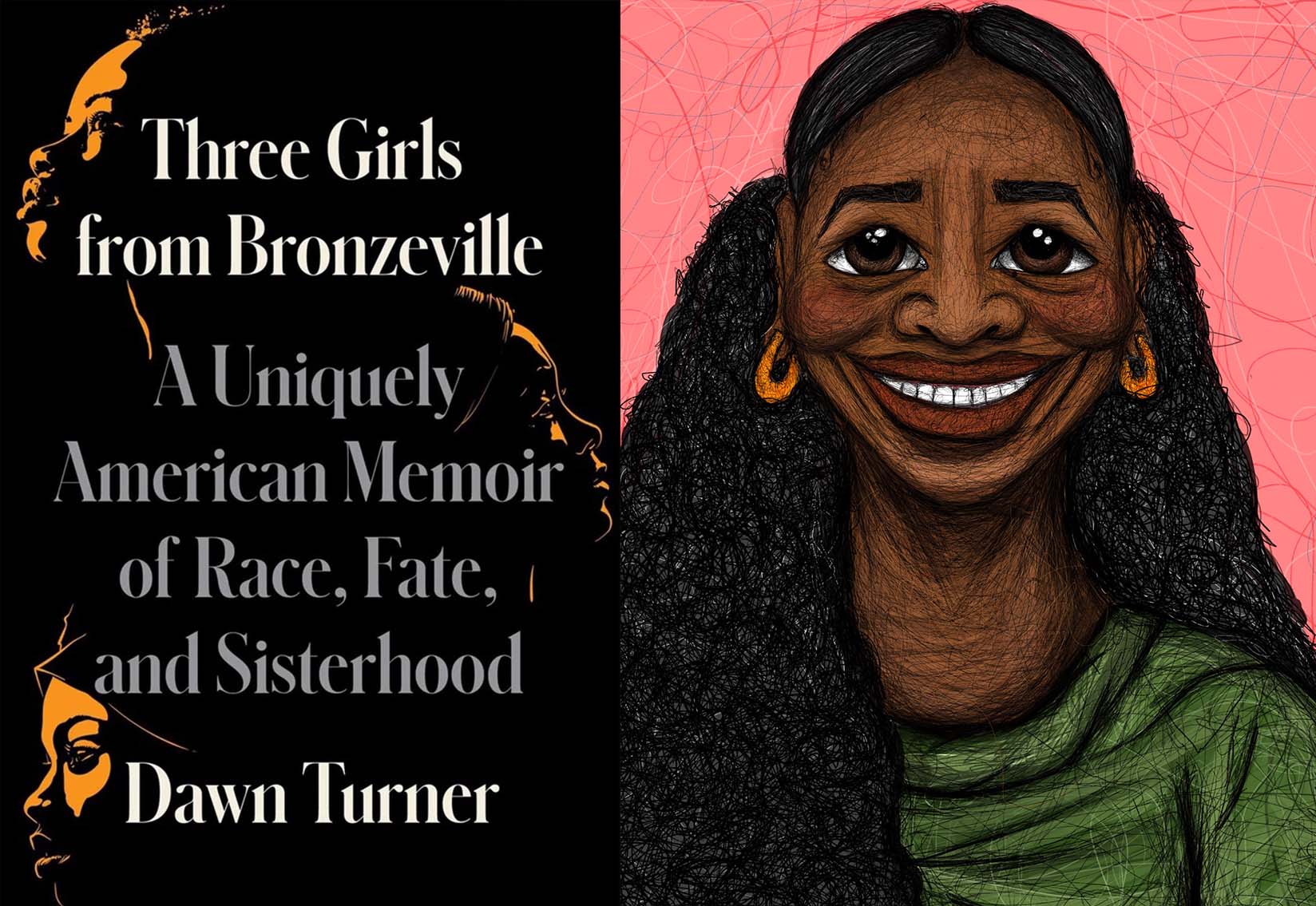

Dawn Turner documents many scenes like these in her new memoir, Three Girls from Bronzeville: A Uniquely American Memoir of Race, Fate, and Sisterhood. Turner grew up in the Lawless Gardens apartment complex off 35th Street with her younger sister Kim and their mother. Dawn’s best friend, Debra, lived in the apartment above them. From this place, all three of their lives would take wildly different turns.

Turner tells the story of herself, Kim, and Debra as they come of age in Bronzeville. After leaving the neighborhood, Dawn achieves remarkable success, while Kim and Debra encounter and inflict almost unimaginable pain and loss. Weaving together personal reflections, original reporting, historical research, and policy analysis, Three Girls from Bronzeville tries to explain what happens when dreams encounter the odds against them.

South Side Weekly spoke with Turner about growing up on the South Side in the 70s, how history and housing intertwine in Chicago, and the lasting bonds of sisterhood.

One of the things that your book conveys is how deep Bronzeville still is in your senses — the smells, the shapes, the sayings, the sounds of the time in the late 60s and 70s. When you think of your childhood, what are those sensory images that come to mind?

Dawn Turner: Well, we need to go back a little bit and start with my great grandparents moving to Bronzeville. My great grandparents arrived in Bronzeville in 1916. My grandmother was three years old and they arrived as part of the Great Migration of Black people moving from the Jim Crow South to the North. They believed Chicago to be the promised land and in the beginning it was. But there were so many things that conspired to change that in the community. So they struggled as a lot of the Black people in the neighborhood did after a few years. And my grandmother said, as I write in the book, Black people “took a bunch of scraps and stitched together a world.” So many of the memories that I imbued the book with come from my grandmother telling us about Bronzeville.

My mother and my aunt grew up there as well, in the Ida B. Wells Homes when that housing project was brand new. I just remember growing up with a part of that inheritance from my grandmother and my mother. In my own experience, I was a kid who grew up in the Theodore K. Lawless apartments. The Lawless apartments were also brand new and unblemished, and I remember in the summer just being able to traverse our world. The grass was always meticulously mowed. There were flowers that were planted, the playgrounds were clean and bright and shiny and colorful. And we were allowed to be kids and to experience that world through that lens of childhood. And for a while it was fairly charmed. And I saw [it was charmed] even after my parents divorced. One of the reasons why I remained so close to Debra is because she rescued my childhood. We became good friends and then best friends. And I was allowed to be a child again.

How did Debra and you become friends at Doolittle Elementary School? It was somewhat of an unlikely friendship; you called yourself a “follower of rules and a maker of lists,” and Debra was most definitely not that.

In the second grade, I used to just stare at her from afar. I was just in awe of this little girl who just always trafficked in trouble [laughs]. And interestingly, she was a lot like my sister [Kim] in that regard. But you know, things look different on someone else than they do on the little girl you share a bedroom with. So I was not attracted to that in my sister, but definitely was in Debra. And I say that Debra and I were best friends, but Kim and Debra were soulmates.

So I first saw [Debra] in the second grade and even though we were in the same classroom, our teacher arranged us according to height, and I was the tallest kid in the class and Debra was the shortest, and so our worlds barely touched. But in the third grade, we were arranged alphabetically. So “Dawn Turner” sat across from “Debra Trice” and that one little logistical shift made all the difference.

I will say that I was attracted to her, but she was attracted to me, too, because we both had something in the other that we were trying to foster in ourselves. The whole idea of opposites attracting. We also learned that we lived not just in the same apartment tower, but that her apartment and her bedroom were directly above mine. That cemented our friendship. I would knock on my ceiling or she would knock on her bedroom floor, you know, just so that we could kind of communicate across the divide. That played a huge role as well.

One of the things that struck me early on in the book is when you wrote, “my earliest memory of myself is of my sister.” How did the arrival of Kim as your little sister change your life?

Some of this is memory and some of this is just what I was told by my mother and father. But I do remember my sister from the very beginning being a mystery to me. She was from the start a headstrong, willful, and fearless person. I was not that person yet and she was from the start. I remember the first time I held her and I thought, “Oh my God, I have no idea what I’ve gotten myself into!” [laughs] I had that feeling of loving somebody so deeply, that, at the same time, you could hate and couldn’t stand [laughs]. I mean, that is the story of siblings and definitely sisterhood, where people are complicated and you are connected by genetics and sometimes you like each other and sometimes you don’t. And that was part of our relationship. But I think at the core we really adored each other, and that was not going to change.

One of the things that your book I think does so well is weave together your personal stories with the larger policy and societal choices that were shaping Black Chicago at the time. You discuss issues like housing policy and redlining and the infamous “Willis Wagons” at overcrowded schools such as Doolittle Elementary. Was that an intentional choice you made when writing the book to highlight issues of discrimination?

Absolutely. So this is a story about people, but it’s also a story about place. It was incredibly important for me to talk about how we lived in this brand new apartment complex, where it was very clear that the way property was kept and the upkeep on the property — that janitors chased down wayward pieces of paper with a religious fervor — was that everything was bright and shiny. The lobbies were incredibly clean, the elevator doors had a stainless steel shine. We had security guards who kind of doubled as doormen — but they were not doormen [laughs], but they would open the doors and we knew them.

That was in contrast with what was going on directly across the street in the public housing complex. As I said in the beginning, when my mother was growing up, the Ida B. Wells Homes was a bastion that offered so many opportunities. It conferred dignity on the residents. They deserved that. Everybody deserves to live in a nice, clean, well-kept place. But by the time we were growing up there, the City had abandoned it. So just across the street [in the Lawless Apartments], we had a bird’s eye view to this. Nothing worked. So garbage pickup lagged over there. It didn’t lag on our side of the street. When a light bulb blew out, the replacement of it took a long time. That didn’t happen on our side of the street. Even the way the police responded; it was either over-policed or under-policed. We were all Black folks. But there was this idea that there were things that people or institutions could get away with in the public housing project.

Even as a kid we knew that there were differences because our complex built a fence around us. We became, in essence, a gated community. Initially it was just a wireless link fence, but there were several entrances that remained open. But as different things started to happen in our community, our fence became more fortified. And the entrances were closed, so there was just a couple of ways in and a couple of ways out of the complex. So people who used to walk through Lawless Gardens to get to 35th Street or something couldn’t do it anymore. I didn’t understand that until I grew up.

What I did understand was that we remained at the elementary school. A lot of parents, including Debra’s parents, moved their kids out of Doolittle Elementary because, in part, the kids from the housing project went there. But my mother said, “we will not be afraid of our own, so we’re going to stay right here.” And the teachers there were outstanding.

Housing is connected to larger effects, then.

It absolutely is. But the book is also about the different policies that deform the community and reconfigured it. And going back to when my grandmother was a little girl, when the City forced the new Black migrants to live in a single strip in the Black Belt—a narrow strip of land along the State Street corridor that began to expand eastward. But there were so many things that happened that put pressure on this community from very early on.

We didn’t understand the history of Ida B. Wells living in the community, Gwendolyn Brooks, Louis Armstrong, the birthplace of gospel music and Chicago blues, and all that talent from politics to arts. We didn’t understand that fully growing up. I certainly didn’t. But later on I did. Talk about stitching together a world! It’s like a universe with not just so few amenities, but so few necessities. And you’re able to create something that can change the world and change the country, and I think that’s huge.

The context of all this connects to what happens to Kim and Debra later in life. I don’t want to reveal too much of that in this conversation, but obviously there are choices and institutions that have a huge impact on their future and that all started in their childhood.

Yes. There are so many young kids today that come into this world and they’re at such a massive disadvantage because of so many different pressures. My heart always aches for those kids. But really, that was not Kim’s or Debra’s story. I mean, they had amazing safety nets. Their families were not at all rich, but they did have resources. I’ll put it this way: I think I had to forgive myself because I felt horrible that I wasn’t able to save them. But I also had to forgive them for making it so hard for us to save them.

That was part of the challenge there as well. Because Debra’s parents were willing to take out a second mortgage on their house when they realized how deep in the throes of addiction she was. This was just to get her into a long-term drug addiction program. And she kept telling them that she didn’t want to do that. [Debra] said she could beat [the addiction]. And it turned out she couldn’t. That would have been huge, just to take a second mortgage out…. But there are people who don’t even have something like that as a resource or an opportunity. Your parents are going to take out a second mortgage just to try to save you?

I do think that choices are often based on conditions. A kid who lives in a beleaguered community is going to have fewer choices than a kid who lives in a well-resourced community. At the same time, race and institutions, all of that stuff, will complicate the picture.

Carr Harkrader is a writer and educator in Chicago. This is Harkrader’s first piece for the Weekly.