It might sound bad to be labeled “radical” by the church, but “radical” describes numerous nuns throughout history who have done good. Nun Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz changed seventeenth-century Mexico through her socially charged writing, despite living in a time when women, including nuns, had limited social power. Today, the works of modern nuns like Sister Kathy Brazda continue to support the radical idea that nuns can use the church as a mechanism to bring about social change. Like Sor Juana, Brazda has been called a “radical”; however, while the term was used to discredit Sor Juana for her activism, today it compliments Brazda’s commitment to social action.

Joel Cruz, adjunct professor at the Lutheran School of Theology, delivered a lecture on Sor Juana as part of the Church in Social Action lecture series from the First Lutheran Church of the Trinity and the Brother David Darst Center in Bridgeport. Brazda herself followed with another lecture, weaving a larger narrative about activism in the church over time. This lecture series calls attention to the church’s often overlooked dedication to social change. By discussing the challenges faced by activist nuns of the past, Cruz’s lecture aimed to show that, historically, “radical” nuns have not just advocated for political or social extremes, but they took risks for the ideas they supported. Radical nuns have a long history of fighting for theological and social change in the face of threats, orders to retract their writings, and, in Sor Juana’s case, the Spanish Inquisition.

Cruz’s lecture explained that Sor Juana was born in mid-seventeenth century Mexico City to a mother who remained unmarried in order to legally retain ownership of her successful farm. Progressively-minded from a young age and dedicated to education, Sor Juana entered a cloister in order to continue the education that would be unavailable to her as a housewife, the other major option available to women at the time. A poet, playwright, scholar, and theologian, Sor Juana owned 4,000 books, at the time the largest library in the Americas.

In her writings, she pushed the boundaries of what women could write, covering topics that had been previously only available to men and speaking openly against sexism in the church. She wrote extensively about the church’s tendency to blame women for catastrophes because of the temptation posed by female sexuality, a problem the church solved by cloistering nuns to protect their purity. In one poem, Sor Juana wrote, “Silly, you men so very adept / at wrongly faulting womankind, / not seeing you’re alone to blame / for faults you plant in woman’s mind.”

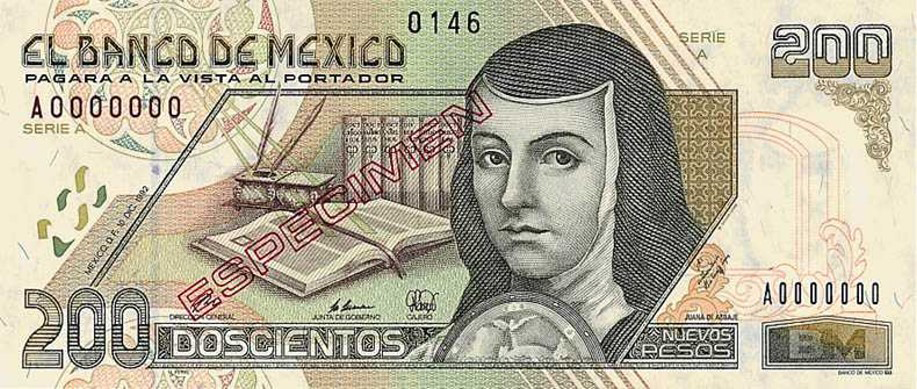

While primarily focusing on women’s advocacy, she also spoke for other groups oppressed by the Spanish government and the church in seventeenth-century Mexico, including, Cruz said, Native Americans, descendants of the Aztecs, and Afro-Latin people. In addition to writing a church-commissioned carol featuring a black Mary, Sor Juana sought to educate audiences, including Spanish royalty. In the prologue to a play performed for the King of Spain, she wrote that Native American religions were not satanic and did not need to be destroyed in order to spread church doctrine, as they contained ideas similar to church teachings. Sor Juana stood up for what she believed, to the point of being investigated by the Spanish Inquisition. Centuries later, Sor Juana’s admirers have thanked her by putting her picture on the two hundred and thousand peso bills and by writing novels, plays, movies, television series, and even an opera about her life and work.

Beyond the art she created and inspired, Sor Juana’s legacy lives on in the work of contemporary nuns who dedicate their lives to using the church and its teachings to inspire social change. Today’s radical nuns still form the backbone of progress and social change within the church, inspiring and directing social action. Brazda, of the Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph, is one such nun.

Both Brazda and lecturer Cruz have been involved in Chicago church life for years. Because of Cruz’s expertise and Brazda’s work, both were natural choices to discuss the continued relevance of socially active nuns to present-day Chicago. Cruz’s lecture on Sor Juana depicted the seventeenth-century foundations of the social work of nuns like Brazda. Where Cruz’s lecture left off, with a commentary on the lasting influence of Sor Juana’s work, Brazda’s lecture on her work in modern church social activism began.

Like Sor Juana, Brazda’s social action has always been rooted in the church. When asked by her congregation why she became a nun, Brazda said, “I came to religious life because I felt at home with the community.” From her first involvement with the church, Brazda has been inspired by the deep connection she feels between her duties as a nun and her dedication to her community. To Brazda, being a nun and being socially “radical” are inseparable.

Brazda is the executive director and co-founder of Taller de José (“Joseph’s Workshop”), a ministry in Little Village that helps recent immigrants and underprivileged people access social services by connecting individuals with agencies that provide housing, health care, education, and job opportunities. The sisters at Taller de José accompany people to those agencies for their referrals to ensure that they receive the services they need. For her work, Brazda received the St. Teresa of Avila Award, fittingly named for a woman who championed church reform in the 1500s; Brazda and her fellow sisters at Taller de José, using their positions in religious institutions to stand up for people often oppressed or overlooked, are working in the tradition of radical nuns before them.

However, not all contemporary progressive nuns are as celebrated as Brazda has been. Even today, nuns have been ostracized or silenced for trying to contribute theological work that is more inclusive or socially conscious than Christianity’s status quo. Until last spring, the Vatican was attempting a takeover of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious, a U.S. nuns’ organization. The Vatican sought to stop the nuns from advocating for contemporary social justice issues within the church, including gay rights and feminism, and had been interfering with the organization since 2012.

The conflict points to how modern nuns can face similar struggles to those Sor Juana confronted in the seventeenth century. While Sor Juana, Brazda, and other nuns have advocated for social change throughout history, church officials in both the Inquisition and the modern Vatican have countered their efforts, labeling them as “radical” or “dangerous.” While such attacks could be considered a reason to give up, “radical” nuns have taken these challenges as acknowledgements of their potential social power and continued their fight, making the work of women like Brazda possible. In the face of the Inquisition, Sor Juana kept writing. In the face of the Vatican’s opposition, the Leadership Conference of Women Religious stood behind its theological positions. Brazda and other nuns at Taller de José support these “radicals” and act on their beliefs to make the world a better place. More so than the church’s response this dedication to social justice is what makes these sisters radical.

I love Bridgeport & I love radical nuns! There’s also an amazing group of nuns in Austin organizing the St. Angela school. I know it’s not the South Side, but I’d love to see a story about those women.

Sr. Carolyn and I, (Sister Donna) work in the South Side of Chicago and we would love to introduce you to our “radical” work. 773.653.5467 or liettecpps@aol.com

Let us not forget that Sor Juana was the patroness of the Decima Musa night club, a center of radical Latino thought for many years in Pilsen. Also, you do not have to go far in Chicago for radical Catholicism. Consider Pat and Patsy Crowley (look them up). Anyone covering this beat should familiarize themselves with all of that.