Ahead of the 2020 Census, Illinois activists and politicians began to try and put an end to politically motivated gerrymandering by advocating for the creation of an independent, nonpartisan commission that would redraw legislative and congressional districts. So far, eighteen states rely on some form of such commissions to shape political boundaries, but in Illinois, redistricting remains the sole purview of whichever party controls the General Assembly. This leaves the majority party free to gerrymander districts, manipulating electoral boundaries to favor their candidates and make elections less competitive. While this redistricting reform effort has gained notable support in Illinois in recent years, the road to its full realization remains long.

Efforts towards reform have taken different approaches over the years. In 2015, activists lobbied for a constitutional amendment that would enshrine redistricting reform. Efforts to put the amendment on the ballot were shot down by the Illinois Supreme Court the same year, but activists came back in 2020, once more pushing for a constitutional amendment in an attempt led by the organization CHANGE Illinois. Their efforts were again thwarted when the coronavirus pandemic prevented the General Assembly from meeting, so in 2021 activists began to push for a less permanent solution—legislation. Three Republican lawmakers filed a bill on Jan. 5 that would have reformed redistricting, but it died in committee when the new General Assembly was sworn in on Jan. 13.

These perennial failed attempts to reform remapping seem to highlight a strong public desire to change how Illinois’ districts are drawn, but also raise the question of whether the state’s redistricting process will ever be reformed. As things stand, the push for reform is ongoing—even while activists acknowledge that the likelihood for change to the 2021 mapping process is highly unlikely.

According to CHANGE Illinois policy director Ryan Tolley, to make the most of the current situation, proponents of redistricting reform need to include more public input on how politicians draw the maps. Currently, the state legislature is required to have eight public hearings on the matter. In 2011, the state held even more public hearings, Tolley said, but when the final redistricting proposal was presented, the state legislature voted on it in less than twenty-four hours. That rush to approval “gave no time for the public to understand what their district would look like, how it would affect their day to day life, their representation,” Tolley said. “So making sure that the public has time to weigh in before the vote is taken is crucial.”

CHANGE Illinois also wants the 2021 redistricting map to ensure that minority groups are fairly represented in state government. Such considerations can lead to congressional districts that appear gerrymandered to those unfamiliar with the racial and ethnic politics that underlie them.

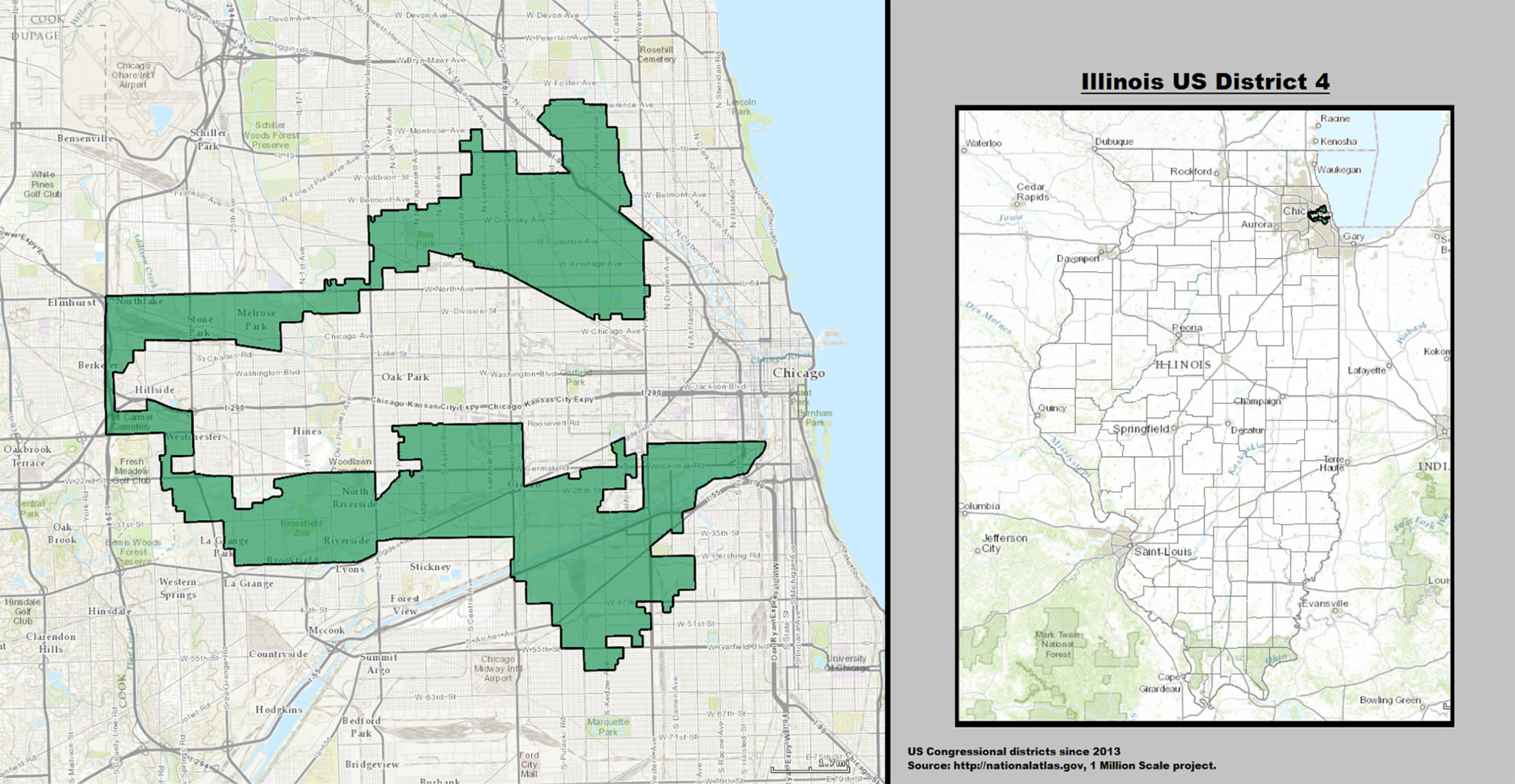

Represented by Jesus “Chuy” Garcia since 2019, the 4th Congressional District—which includes several heavily Puerto Rican neighborhoods on Chicago’s Northwest Side, then wraps around Oak Park and a few other western suburbs before returning to Chicago on the predominantly Mexican-American Southwest Side—is commonly referred to as the “earmuff,” Tolley said. “A lot of folks look at it and say, ‘that’s a gerrymandered district.’ The district was actually created [in 1991] because there was a growing Latino population that was not represented in Illinois.”

“Our [state] constitution restrains what types of reform we can have going forward for this upcoming remap,” Tolley said. Because of that, CHANGE Illinois believes a constitutional amendment remains necessary for any redistricting reform.

On Jan. 8, during the General Assembly’s lame duck session, Rep. Tim Butler (R-87th) proposed a bill that would have taken redistricting out of the hands of politicians altogether. The bill potentially would not allow the Illinois General Assembly to have any say in the redistricting process—not even a final vote. But the state constitution requires the General Assembly to manage redistricting, so Butler’s bill may have been unconstitutional, which is partly why CHANGE Illinois is still pushing for a constitutional amendment.

Political scientist Thomas Ogorzalek, co-director of the Chicago Democracy Project at Northwestern University, says redistricting reform is unlikely to happen in Illinois. Moreover, he doesn’t think it will solve the problems that activists say that it will. “A lot of activists think that getting rid of gerrymandering or partisan drawing of district lines would be a cure-all, and political scientists don’t think that’s true,” Ogorzalek said. Instead, there are other issues aside from gerrymandering.

Gerrymandering usually results in one party getting more seats than expected—but this is not a problem that Illinois suffers from, Ogorzalek said, and it also can’t be completely solved by redrawing districts.

A problem that Illinois does have is a bias toward protecting incumbents, allowing established politicians to keep their seats and making it hard for challengers to break into the game. But this also can’t be blamed completely on gerrymandering, Ogorzalek said. “We also see high levels of incumbency advantage in places where gerrymandering doesn’t happen, like the US Senate.”

Ogorzalek also questioned how nonpartisan the proposed commission would be. “Just because you’re ‘not partisan’ doesn’t mean you don’t have political goals or political preferences,” he said. “Those things that are non-partisan often lead to outcomes that … partly harm working-class interests, make it harder for certain kinds of [representation] along lines of class and race.”

“One of the challenges with setting up these independent commissions is that ultimately, they’re [still] going to be created by people,” he said.

And so even though work activists are doing to reform redistricting is a step in the right direction, “for Illinois, it’s a step that is less urgent than in other places,” Ogorzalek said.

“I’d be skeptical that they’re going to make major reforms or changes to this process [in 2021],” Ogorzalek said—largely because the Democrats that form a majority in Illinois would be unlikely to change a system that has so far benefited them.

Unfortunately for those who prefer (relatively) quick fixes, Ogorzalek said true solutions to problems frequently blamed on gerrymandering are much bigger. The biggest fix, he says, is proportional representation; political parties will gain seats in proportion to the votes cast in the party’s favor.

Proportional representation doesn’t exist in the U.S., but has been a broadly used reform in Europe. Although this wouldn’t solve all of America’s political woes, it would solve its gerrymandering concerns. Failing this, Ogorzalek said, parties could also tweak their positions to make them more competitive in areas where they don’t currently have wide support; for Republicans, this is generally urban areas, for Democrats these tend to be more rural parts of the country.

A novel solution called “define-combine,” proposed by Maxwell Palmer, a political scientist at Boston University, would allow one party to draw twice as many districts as are needed, and the other party to combine adjacent pairs to create the final map. But this theory is untested—“It seems to work better on a computer, but we’ll see,” Ogorzalek said.

For now, the General Assembly remains in control of redistricting. Governor J.B. Pritzker said he will veto any overly partisan map.

Corey Schmidt is a DePaul University student and an associate editor of 14East Magazine. He last wrote about the best green spaces in Back of the Yards. Jade Yan is a staff reporter for the Weekly who covers politics and police reform. She last covered community reactions to Mayor Lightfoot’s 2021 budget.