The short film CHAOS, written by Chicago native Jasmine Barber, also known as J Bambii, depicts the disorienting experience of Black girlhood. Barber is an artist, tarot reader, and founder of the music showcase series The Brown Skin Lady Show. Released on Halloween and joining a lineup of recent Afro-Surrealist media, such as The Other Black Girl and Atlanta, CHAOS portrays the absurdity and horror of the Black experience, and specifically internalized racism.

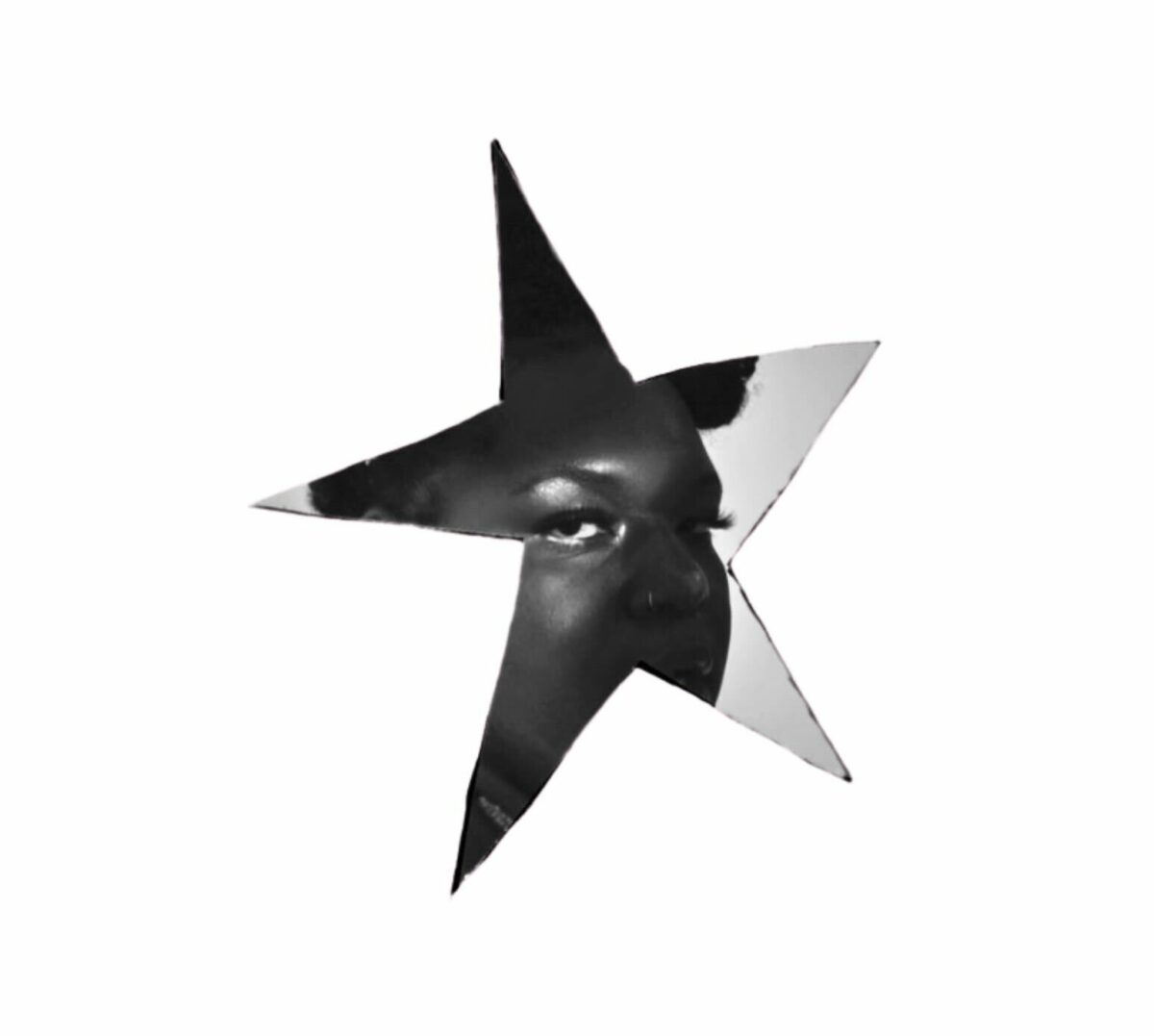

CHAOS holds up well all on its own, but when in conversation with Barber’s musical discography, a larger universe unfolds. She dropped the soulful boom-bap EP Retrograde under the name J Bambii in December 2018. The three-track project touches on a range of topics and Barber is a confident emcee who intertwines childhood nostalgia, feelings of apathy toward a complicated world, and the effort to be her authentic self into the lyrics. The EP’s cover features a school photo of a young Barber wearing a pink sweater adorned with small purple tulips. Her hair is styled in large curls and a metallic ball secures a curly ponytail on top of her head. She appears completely unconcerned with the camera in front of her. The YouTube description holds a single Audre Lorde quote: “I have come to believe over and over again that what is most important to me must be spoken, made verbal and shared, even at the risk of having it bruised or misunderstood.”

CHAOS depicts this bruising—what it looks like to be vulnerable and be met with a very specific kind of violence. Navigating Black girlhood is the paradox of being told that your blackness is all at once too much and not enough, even by other Black people. With the entire film shot in black and white, it seems like a memory, dated. A discomfort presents itself to the modern-day viewer, as the film and its events should feel older, but viewers can sense that the same ideologies are present today. This element lends itself to the film’s thematic style, which is similar to that of an old-school horror movie.

The film’s opening foreshadows the negation of a happy, uncomplicated ending for someone who exists in a body like Barber’s. Two young lovers hold hands, dreamily staring into each other’s eyes as a horn swells. They sit comfortably outside on school bleachers, leaning in for a kiss. The music turns into a sudden shriek, and the two disappear to reveal a young Jasmine (portrayed by Harlem West) daydreaming in class. Jasmine gazes at her crush from across the science room and later gives him a note with the question, “Will you go out with me?” followed by “Yes” and “No” checkboxes.

In the next scene, the absurd is introduced as a group of Black boys insult Jasmine in ways that are tinged with internalized racism. The boys compare her to famous Black characters who have become synonymous with ugliness: “Man, he finna go hang out with Precious big ass.” She’s also likened to Whoopi Goldberg in The Color Purple along with a string of insults about her weight. The crush, played by hip-hop artist $imba P, is mocked by his friends for hanging out with Jasmine. Their mouths fill the screen as the friends trade insults about her and the soundtrack becomes something out of a thriller, foreboding and dangerous.

The scene holds a palpable weight, displaying a tension and absurdity that carry the film and sync up with Afro-surrealist techniques. CHAOS uses the behavior of the boys to add additional layers to a situation that could be seen as teenagers behaving poorly. The layers of the story build as the viewer moves through the film displaying a reality that can seem nightmarish but still accurately represents the complex reality of Black people. In this scene, we understand that these boys have learned to mock a reflection of themselves, their mothers, sisters, and aunts. This issue is highlighted later in the film when the boys end up in detention and Jasmine’s best friend (played by Chima Ikoro, the Weekly‘s Community Builder) says, “Who’s going to pick you up from detention? Your Black ass mama.”

What’s even more potent about the scene is the intentionality in the insults. Black media figures such as Precious from the eponymous film and Celie from The Color Purple are identified within their individual cinematic worlds and in real life as unattractive. They are both dark-skinned, poor, and considered either too skinny or too fat. Despite their significance in film history, they have both been criticized for perpetuating Black stereotypes. This criticism is not only a depiction of how these boys perceive Jasmine but also a reflection of how she is often viewed in society and how society forces her to see herself.

CHAOS continues to explore internalized racism throughout the rest of the film, displaying what should feel like dated racial ideologies. In true horror fashion, a spiraling piano medley introduces us to the worst-case scenario: Jasmine gets the note back with “Fat Black Bitch” written across her original question. She’s later pictured watching Tyra Banks berate a girl on the 2000s series America’s Next Top Model. Tyra’s monologue, in this context, feels like a device to point out the ridiculous responsibility placed on Jasmine to change something about herself after the note incident. “We were rooting for you; we were all rooting for you—learn something from this!” Immediately after, a skin-whitening commercial appears on screen and begins to haunt Jasmine. The over-the-top, cream-slathering ad, featuring the line, “This is the skin to die for,” is unforgettable—an illusory and horrific moment. At this point, we finally learn more about how Jasmine’s self-image is influenced by the world around her.

But what stands out most in this film is J Bambii’s rap interlude, which takes a closer look at the patterns in Jasmine’s romantic life and the tension created by her Blackness, hair, and weight. It’s a dynamic scene within the film, featuring Jasmine as Frankenstein’s bride, an even younger version of Jasmine dancing innocently, and a mad scientist mixing a skin-lightening potion. The lyrics illustrate the effort to live authentically and loudly: “Add the weight/ I’m breaking seams bitch.” There is an obvious confidence, a sense of acceptance that has been reached, but on the other hand, the bruising is also obvious: “Keep these niggas in yo dreams bitch/ hurt by what you heard and seen, shit.” With this scene, Barber vulnerably communicates the contradictions of her experience, highlighting how young Black girls learn to navigate societal expectations while remaining true to themselves. She also explores the jarring experience of encountering racism within one’s own community.

Despite its use of disorienting film techniques, such as its black-and-white aesthetic, a set of instrumentals, and surrealist visual effects, the nine-minute film manages to stay grounded in reality. It never displays traumatic images for shock value or veers into overly campy elements. CHAOS is a worthwhile watch to understand the complicated emotions and experiences associated with internalized racism. Although it’s not a joyful film, there is an undercurrent of hope—and a silent ask for the world to be a little kinder to Black girls.

Arieon Whittsey (they/them/theirs) Is a storyteller who has recently made their home in Chicago. They are an enjoyer of all forms of media, especially contemporary novels that make them cry and music that makes them dance.

Well done Arieon! A lucid, engaging review of a film with something new and powerful to say about Afro-surrealism as a lens worth peering into — and through.