On Sunday afternoon, under gray skies and cold weather, East Side residents, and the group Bridges//Puentes: Justice Collective of the Southeast met at the East Side Memorial at the intersection of Indianapolis Ave. on 100th Street and Ewing Avenue. Organizers and participants painted each other’s faces with zombie makeup to symbolize the diseases and death caused by polluters in the area.

The group greeted cyclists coming from neighboring communities: Hegewisch, Slag Valley, Bush, South Deering, South Chicago, and even the Southwest Side. Some came ready with zombie or Day of the Dead face paint; some mounted signs under their handlebars and bike frames to show their opposition to General Iron’s relocation to the Southeast Side.

Environmental racism had taken a seat at the table during the second and final presidential debate a few days earlier. President Donald Trump focused on heavy industries’ profits; former Vice President Joe Biden focused on the health and safety of vulnerable communities located beside mills, factories, and oil refineries. It was a very stark contrast in priorities. And yet, while Biden thinks these companies pose a threat to people’s health, Trump’s response was, “The families that we’re talking about are employed heavily and they are making a lot of money, more money than they’ve ever made.”

But that is not a reality for Samuel Corona, forty, a community activist, father, and long-time resident of the Southeast Side, one of the many fenceline communities along the Calumet River’s industrial corridor. He became involved in his community after returning from the Marine Corps. and noticing that some of his children had breathing problems in the summers. They would be out of breath and had the same symptoms as asthma. “I’m not a rich man so what am I giving my kids to inherit? Polluted air, polluted soil, polluted water?” Corona asked.

Corona is talking about the long history of pollution caused by companies operating in the area: U.S. Steel, KCBX, and now General Iron, the controversial metal scrapping facility slated to be relocated from Lincoln Park to East Side despite years of community pushback (and several explosions at its former location). He points to the city and local leaders. “We need to take a look at how the city allows for such loose regulations. It creates a condition where these communities are prisoners in their own homes.”

Crystal Vance Guerra, thirty-two, an organizer with Puentes//Bridges, says this type of creative, theatrical, or performance-based action was born out of the police shooting of George Floyd in May, the Black Lives Matter protests that followed, and the COVID-19 crisis. “We’re at the brink,” Vance Guerra said.

Since May, the group has mobilized around social justice issues such as police brutality and immigration. “People are dying, there are no jobs, children at the border are put into cages, police brutality is happening… we have nothing to lose,” Vance Guerra said.

As the event began, protestors handed out signs and sold face covers and t-shirts with a clear message: General Iron Out, End Environmental Racism.

Then about a dozen cyclists made their way two miles south where they would join a rally at George Washington High School, before marching to the home of 10th Ward Alderwoman Susan Garza, who has failed to block General Iron’s relocation or fully engage residents on the matter. The march and rally were spearheaded by high school students: the younger voices now surfacing in the area. They do not want to inherit the polluted air, soil, and water that Corona spoke about.

“Washington is mere feet away from the relocation site of General Iron… a metal polluter, so we’re really just working towards making sure our students don’t breathe that air,” said Trinity Colón, seventeen, a student leader of the group Student Voices. “They are taking advantage because the school is low income, and predominantly Latinx, as well as the community in general.”

Washington High School is the only public high school in the East Side neighborhood. It has a student population of 1,440 with a minority enrollment of ninety-five percent (majority Latinx), and eighty-six percent low-income students, according to the Illinois State Board of Education.

“The reason this march is happening is because time and time again, we have asked our elected leaders, like Garza, to do simple things like write a letter to the mayor and [Public Health Commissioner Allison] Arwady to state publicly that she doesn’t want this to happen in the neighborhood,” said Chuck Stark, a science teacher at George Washington High School, to the crowd of concerned students, families, and residents in front of Garza’s home.

According to Stark, the night before the rally, Garza informed the students that she was not going to send a letter to city officials. “She will do it in private but not in public, and that is why we have these students saying, ‘enough is enough,’ ” said Stark.

The Weekly reached out to the alderwoman’s office on Sunday for a comment, but did not receive a response. In previous statements, Garza has said that she wanted to put a halt to environmental permits and licenses until meaningful public engagement on these facilities can take place. Garza also stated that due to COVID-19, community residents were not able to participate. But in October, the alderwoman said she didn’t know that one of the two required permits needed to relocate General Iron had passed and, according to Block Club Chicago, the city did not post any type of public notice of the approved permit for more than two weeks. One city permit is still pending.

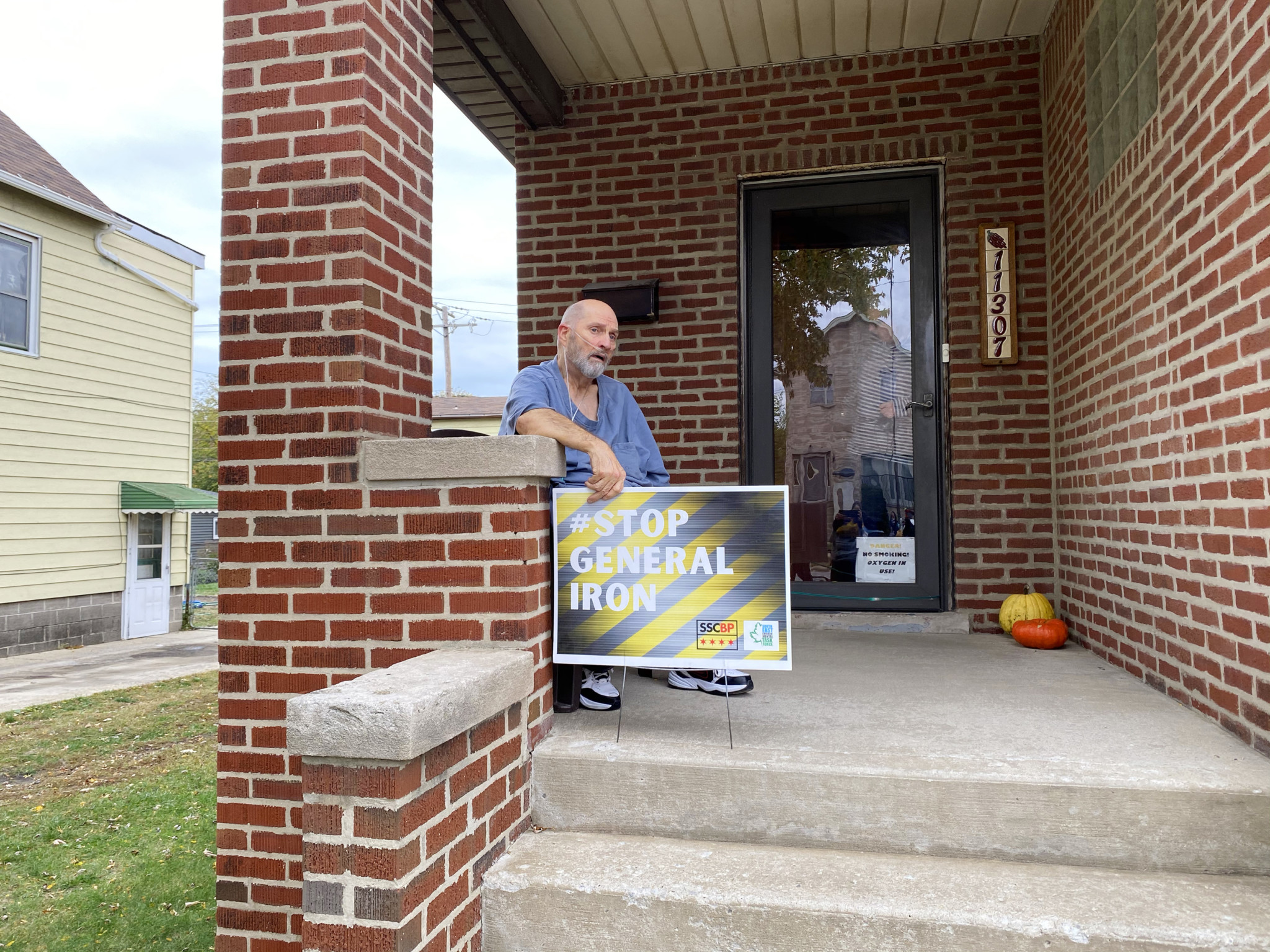

On the way to Garza’s home, Jerry Crum, seventy-three, was sitting outside his home on 113th and Avenue O. He held up a sign emblazoned with the words “Stop General Iron” and waved his hand, signaling his support to the protesters. Crum had an oxygen tank beside him with tubes connected to his nose to help him breathe. He’s lived on the Southeast Side since he was twelve years old.

“When I was a kid, there would be so much stuff landing on the house. Republic Steel would send people over to paint it free for you. That was a good clue right there… back in the day.”

Crum said many friends and neighbors got sick and some died from pulmonary problems, just like his father did. “I didn’t know it was blowing through the air, but apparently it has been.”

The Chicago Police Department showed up at the school rally, followed the march to Garza’s home, and circled protestors throughout the action. Upon arrival at her front steps, residents rallied and demanded she come out. Colón attempted to knock on Garza’s home, but a police officer intervened and asked her not to trespass on private property. Garza did not open the door, and it was not clear if she was home.

“There’s been a lot of conflict with her, a lot of backlash,” said Colón. “There hasn’t been a space for us to interact with her, especially around topics like this… she is not listening to young people.”

COVID-19 has also played a big role in the mobilization of students. “I think there’s been a lot of reflection in the community, in terms of where they live,” Colón said. “It’s not as nice from the outside as other communities, but we deserve for it to be.”

At the East Side Memorial where the day started, an M60 tank sits in the same place it was installed nearly half a century ago. There are two metal signs attached to a stone monument beside it. One reads “East Side Memorial” and dangles at its side—the bolts that held it up broke. Another metal sign that used to be there simply read: “East Side.” The memorial was installed in 1979 to recognize the role of the steel mills and local workers in producing armaments during World War II.

On the viaduct walls that connect 100th Street and Ewing Avenue is a mural that is chipping away. Freight trains run above, and all of it is under the Chicago Skyway. The viaduct’s forgotten mural has a faded cargo ship. On the cargo ship is the phrase, “Pride of East Side.”

In August, local environmental groups on the Southeast Side filed a civil rights complaint with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). The complaint states the decision to allow General Iron in the East Side is “just one discrete instance of the City of Chicago’s longstanding and ongoing effort to facilitate the relocation of industries from white, affluent neighborhoods to Black and Latinx neighborhoods.”

HUD is currently investigating if housing discrimination has taken place in the area during Lightfoot’s administration.

On October 21, two ministers also filed a federal lawsuit to stop General Iron from moving to the 10th Ward, alleging that Lightfoot’s administration has engaged in environmental racism by pushing through two permits for the clout heavy shredder, and doing this without public notice.

According to the lawsuit, General Iron and the facility’s former owner, the Labkon family, has contributed $750,000 to influence City Hall officials since 2005. Among the biggest recipients are Zoning Chair Alderman Tom Tunney ($62,250), Finance Chair Alderman Scott Waguespack ($30,500), Ethics Chair Alderwoman Michele Smith ($24,500), and Environmental Protection Chair Alderman George Cardenas ($41,750).

“Our faith communities, like Black and Brown communities across this city, are being forced to accept yet another bad polluting neighbor. General Iron is just the latest in a long list: MAT Asphalt, Hilco and Sims Metal Management,” said Rev. Roosevelt Watkins III, pastor of Bethlehem Star Missionary Baptist Church, in a statement.

“Simply put: the South Side gets the scrap yard; the North Side gets Lincoln Yards.”

Update, October 28, 2020: This piece has been updated to include the recent lawsuit.

Correction, February 16, 2021: Some aldermen contributions were updated.

Alma Campos is a bilingual reporter based in McKinley Park. Her writing has appeared in Univision Chicago and WTTW and focuses on immigrant and working-class communities of color in the South and West Sides. This is her first story for the Weekly.