Before last August, this year’s election for the three open seats on the board of commissioners that governs the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago (MWRD) looked like it’d be a rather uninteresting affair. The district, which is responsible for wastewater treatment and stormwater management in Cook County, has historically been controlled by the Democratic Party; with three incumbent Democrats seeking re-election, the outcome seemed all but settled.

Those three incumbents—Cam Davis, Kim Du Buclet, and Frank Avila—each appeared heavily favored to win re-election. Davis had just won his seat on the board, filling the two remaining years of deceased Commissioner Tim Bradford’s term through one of the largest write-in campaigns in Illinois history. Du Buclet faced no opponents in the 2018 primary to fill the remaining two years of Cynthia Santos’s term, who had been appointed to the Illinois Pollution Control Board by then-Governor Bruce Rauner, and won seventy-seven percent of the vote in the general against a Green Party opponent. Avila, for his part, had comfortably won re-election in 2008 and 2014, and seemed likely to coast into his fourth term on the board.

The Cook County Democratic Party’s slate-making session in August, however, produced an unexpected outcome. Avila, who was endorsed by the party in 2014 and 2008, was unceremoniously dumped from the party’s slate and replaced with northwest suburban Hanover Park Village Clerk Eira Corral Sepúlveda. The reason why remains unclear: the Daily Line reported that the party’s Latino Caucus “spearheaded” the move, while its reporter Alex Nitkin tweeted out an acrimonious exchange between Avila and 41st Ward Democratic Committeeperson Tim Heneghan. When the Weekly asked Avila what happened, he professed ignorance, saying that he “can’t speak to the process” and didn’t know why he didn’t win the endorsement.

Avila, who won his first term in 2002 without the party’s endorsement, wasn’t going to go quietly. He put together a slate, teaming up with Deyon Dean, the former mayor of south suburban Riverdale, and northwest suburban Des Plaines municipal employee Heather Boyle to create a ticket with the racial, gender, and geographic diversity needed to win votes across the county. Although Avila hasn’t directly attacked the other candidates, his son (also named Frank) has been active on Twitter, criticizing the county party’s slate as “puppets.” Avila’s campaign has also endorsed a handful of other candidates challenging the party committeepeople who, though we don’t know the exact vote breakdown, may have voted to endorse Sepúlveda over him. He’s backing Yessenia Carreon in the 10th Ward against Alderwoman Susan Sadlowski Garza and Bill Morton in the 49th Ward against state Representative Kelly Cassidy.

The slates don’t seem to disagree on much—all the candidates the Weekly has spoken with professed a desire to tackle urban flooding and reduce the district’s carbon emissions, and all of them seem happy that the district finally has an inspector general, through a contract with the county Office of the Independent Inspector General, to provide independent oversight of the district—historically a bastion of patronage. The general sentiment seems to be that the district, which has a budget of $1.2 billion and 2,000 employees, is doing pretty well (which makes sense, since both slates feature at least one incumbent commissioner).

With six candidates now splitting the vote, Avila’s slate also creates an opportunity for candidates not affiliated with either slate to sneak into the top three. Southwest suburban Crestwood Village Trustee Patricia Theresa Flynn, for example, has built up a strong base with labor unions, winning the support of the Chicago Federation of Labor. In a split field, having a strong appeal to a particular constituency might be enough to win.

Michael Grace, vice president of the South Lyons Township Sanitary District in the southwest suburbs, appears to be pursuing a similar strategy. Grace, who has largely self-funded his campaign, has announced endorsements from the mayors of Indian Head Park, Elmwood Park, Melrose Park, and Countryside, as well as state Senator Bill Cunningham, who represents Beverly and the southwest suburbs. Grace also commands the first line on the ballot, an important factor in low-profile elections like this one. If he can gather enough votes from suburban communities, or just from voters who punch the first name on the ballot, he might be able to win.

Two other candidates, Mike Cashman and Shundar Lin, are campaigning on their experience. Cashman, a social studies teacher and championship-winning water polo coach, is running on a platform that emphasizes education, saying that the district needs to do a better job of educating the public on issues like the overuse of road salts. Lin, who has a PhD in sanitary engineering and an impressive academic résumé—including a stint as an appointee of then-Governor Rod Blagojevich to the Illinois Pollution Control Board—believes that the district could use someone with his expertise in wastewater resources.

Who’s Funding Who?

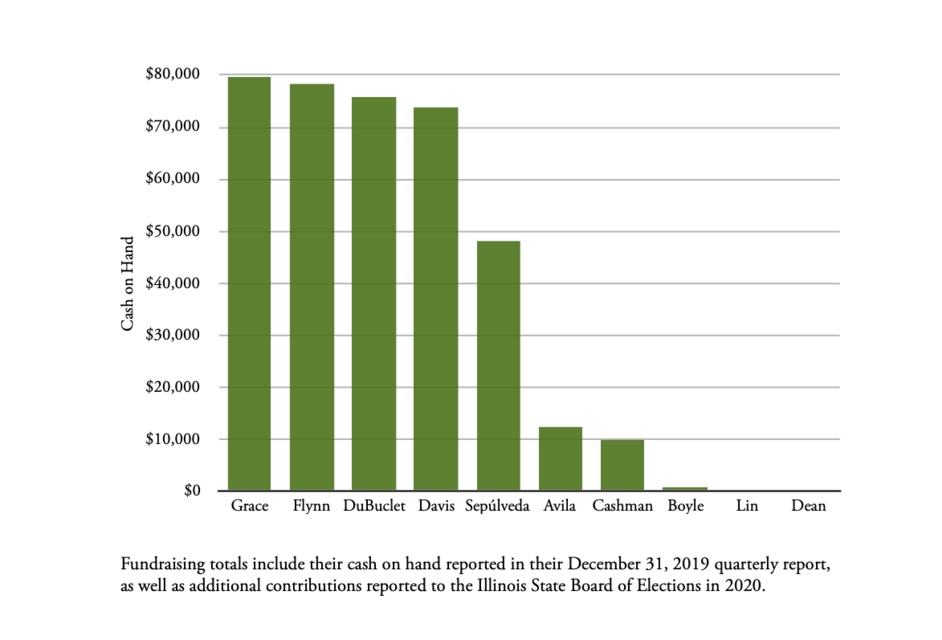

Frank Avila: Being dropped from the Democratic slate doesn’t seem to have substantially hampered Avila’s fundraising prowess. Since being dumped in August, he’s raked in a few thousand from a diverse array of MWRD contractors: $350 from Daniel Jedrzejak, an engineer with MWRD contractor Chastain & Associates; $175 from Chetan Kale of KaleTech; $250 from Baxter & Woodman; $300 from Engineering Resource Associates; $300 from Burns & McDonnell Engineering; $500 from American Surveying and Engineering, $300 from Burke Engineering; $500 from Interra; $500 from Rubinos and Mesia Engineers; $500 from Wynndalco Enterprise, and $300 from Manhard Consulting. Notably, only Christopher Burke Engineering has donated to both Avila and Sepúlveda; contractors appear to be choosing a side.

Some of his biggest checks, however, have come from labor, including $2,500 from IBEW Local 134, $5,000 from a PAC controlled by IUOE Local 150, and smaller donations from Painters District Council 14, Plumbers Local 130, and IAM Lodge 126. He has far fewer donations from politicians than Sepúlveda, but the handful he’s collected are notable names: former mayoral candidate Willie Wilson, 26th Ward Alderman Roberto Maldonado, and MWRD board president Kari Steele. He has also loaned himself nearly $23,000.

Heather Boyle: Her only reported donation is $1,000 from Archon Construction, an Addison-based construction firm with several district contracts.

Mike Cashman: Cashman has recorded around $13,000 in donations, mostly from individuals, as well as loaning $3,500 to himself. One notable donor: John Doerrer, the former head of Richard M. Daley’s Office of Intergovernmental Affairs, who chipped in $250.

Cam Davis: Davis has mostly recorded contributions from individuals, many from the environmental movement. Some notable names include Howard Learner, the executive director of the Environmental Law & Policy Center; Dr. Marc Gaden, communications director for the Great Lakes Fishery Commission; Debbie Chizewer, who leads Earthjustice’s Midwest office; and Stephanie Comer, president of the Comer Family Foundation, a major donor to environmental research. He’s also won support from a variety of Democratic politicians, including former Evanston Mayor Elizabeth Tisdahl and fellow commissioners Debra Shore, Josina Morita, and Kari Steele, as well as a usual lineup of labor unions: the Chicago Federation of Labor, IBEW Local 134, SEIU Local 1, Sheet Metal Workers Local 73, Pipefitters Local 597, IUOE Locals 150 and 399, Teamsters Joint Council 25, and the Chicago Laborers District Council.

Missing from the list: any engineering firms with contracts with the district, traditionally one of the more lucrative sources of campaign contributions for incumbent commissioners. Davis pledged to not take those donations; campaign finance data shows that he’s kept his word.

Deyon Dean: Dean has only recorded a couple thousand in fundraising, primarily from his wife Janisse, who also serves as the chair and treasurer of his campaign committee.

Kim Du Buclet: While Du Buclet has raised her fair share of money from civil engineering firms and other district contractors, with at least $9,500 from eight contractors, her largest support by far has been from labor unions. Since November 2018, her campaign has posted eye-popping fundraising reports: $5,000 from SEIU Local 1, $7,500 from IBEW Local 134, nearly $10,000 from IUOE Local 399, $16,500 from the Chicago Laborers District Council, and a total of $20,000 from IUOE Local 150 and an associated PAC. In total, Du Buclet has recorded contributions from nineteen different union locals over the course of this campaign season.

As far as other contributions, Du Buclet has also recorded donations from a variety of Black politicians, including U.S. Representative Robin Kelly, Secretary of State Jesse White, MWRD board president Kari Steele, and Cook County Clerk Karen Yarbrough. She’s also received contributions from other candidates on the ballot: Justice P. Scott Neville Jr., who is running to keep his appointed seat on the Illinois Supreme Court, and Appellate Judge Michael Hyman have both given to her campaign.

Three other donors—all developers—merit a brief note. The campaign received $500 from DL3 Realty, the firm that developed the new Jewel-Osco in Woodlawn, as well as $5,000 from former Cook County Housing Authority head Elzie Higginbottom. The Rev. Leon Finney Jr., a Woodlawn pastor who managed thousands of public housing units before his Woodlawn Community Development Corp. experienced a dramatic bankruptcy last year, also chipped in $250, while Lincoln South Central, a Woodlawn strip mall with ties to Finney, gave another $400.

Patricia Theresa Flynn: Flynn has recorded substantial contributions from labor unions: she’s collected $62,800 from Local 399 of the International Union of Operating Engineers, which represents the MWRD’s operating engineers, along with smaller checks from the IBEW (Local 134), the Painters (DC 14), the Sprinkler Fitters (Local 281), and the Pipe Fitters (Local 597). She’s also recorded contributions from south suburban Crestwood Mayor Lou Presta and from the Farnsworth Group, an engineering firm.

Michael Grace: Grace has largely self-funded, loaning his campaign $119,000.

Shundar Lin: Has not reported any fundraising.

Eira Corral Sepúlveda: Sepúlveda has drawn significant financial support from engineering firms with MWRD contracts. She’s raised $2,000 from 2iM Group, $1,000 from CSI 3000, $500 from ESI Consultants, and $250 from Christopher Burke Engineering, all firms that have been awarded district contracts. She’s also received $300 from Purple PAC, a political action committee that has received contributions from multiple MWRD contractors, including Reliable Asphalt Corporation, Bluff City Materials, Knight Partners, and 2IM Group, and caused a controversy in last year’s 25th Ward aldermanic election for its ties to the owners of a now-closed Pilsen metal shredder.

Sepúlveda has drawn substantial support from current and former Latinx officeholders, recording contributions from 25th Ward Alderman Byron Sigcho-Lopez, 12th Ward Alderman George Cardenas, and 22nd Ward Alderman Michael Rodríguez, as well as Cook County Commissioner Alma Anaya, U.S. Representative Jesús “Chuy” García, and state Senator Celina Villanueva. She’s also won support from labor unions, recording contributions from Painters District Council 14, the SEIU Illinois State Council, and the Chicago Regional Council of Carpenters, as well as a donation from Arnoldo Fabela, director of field mobilization for the Illinois Federation of Teachers.

Who’s Watching the MWRD?

Last April, after 130 years, the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago (MWRD) finally got an independent watchdog. Historically, the district has been a ready source of patronage jobs and inflated contracts for politically connected engineering firms, each seeking their piece of the MWRD’s $1.2 billion budget. The Tribune’s editorial board applauded the move, a long-time priority of Commissioner Debra Shore, as putting the commissioners who unanimously approved it “on the right side of history.” Commissioners Kim Du Buclet and Cam Davis, seeking re-election this year, both mentioned that decision as votes that they were proud to cast during their past two years on the board.

The MWRD did not create its own inspector general; instead, through a three-year intergovernmental agreement with Cook County, the county Office of the Independent Inspector General (OIIG) also handles cases that arise from the district. This kind of agreement is not without precedent: the Forest Preserve District of Cook County has a similar agreement with the OIIG.

This partnership meant the MWRD, which agreed to pay $600,000 annually for this service, would not have to go through the lengthy and expensive process of creating its own investigative oversight agency. As Shore explained in a newsletter to constituents, titled simply “Why You Sent Me,” the agreement gave the district “access to more resources for less money and a quicker start.”

Shore is right—since inking the intergovernmental agreement, the inspector general has already issued three quarterly reports. The office received nineteen complaints during the second quarter of 2019, twenty-three during the third quarter, and sixteen during the fourth quarter. While a handful of those have been declined, most produced an official inspector general case inquiry, the vast majority of which are still pending. Two of those inquiries have found enough corroborating evidence that they have been upgraded to official investigations, while one has been referred to another agency.

By the fourth quarter, a handful of investigations initiated by the OIIG had come to fruition. One review investigated whether commissioners had used MWRD email accounts for political purposes. Five commissioners, it turns out, were playing by the rules: two did not use their political email accounts to send any emails to any MWRD email accounts, while three more had only sent non-political emails.

Four commissioners, however, were a bit more active. One sent invitations to a fundraiser, with ticket prices between $250 and $2,500, to the official emails of ten different MWRD employees. Another sent fundraising emails to two employees, a third sent emails requesting employees join the commissioner at political events like a post swearing-in celebration, and a fourth sent emails requesting staff to add political events to the commissioner’s calendar and people to the commissioner’s newsletter. One particularly notable email from the fourth commissioner talked to a staffer about collecting petition signatures for another elected official.

These emails, as the report explained, “involve the use of MWRD technology for political purpose,” and “may cause employees to feel pressured to contribute to the Commissioner’s political causes in order to keep their jobs [or] advance in the workplace.” The report mentions that several commissioners have verbally committed to asking their political organizations to not contact district employees through their MWRD email addresses, and one sent a written response outlining “additional safeguards” they were implementing to avoid this in the future.

In accordance with the county ordinance that established the OIIG, the report does not identify the four commissioners, but Davis and Mariyana Spyropoulos both told WGN that they were not among the commissioners mentioned. A MWRD spokeswoman also told WGN that the commissioners will not face consequences for the lapse.

Two additional investigations were concluded in the fourth quarter. One complaint suggested that the MWRD’s director of information technology had improperly failed to address a technical vulnerability in the district’s servers. The OIIG, however, found that the director had installed recommended software security patches and had responded appropriately to the vulnerabilities.

The second investigation related to an incident where an engineer fell into a channel of untreated sewage at the Calumet Water Reclamation Plant and was pulled out by another employee. While the complaint claimed the accident had not been documented or investigated, the OIIG investigation found that the MWRD “conducted a prompt and comprehensive investigation” and produced a “very thorough” report on the incident. Additionally, the complaint alleged that the employees were not disciplined for the incident, but the OIIG found that “appropriate disciplinary action was imposed on [the employees] and to their supervisors.”

As well as those three completed investigations, the OIIG also collaborated with the MWRD’s Law Department to refine and update the district’s Ethics Ordinance. An amended version of the ordinance was adopted unanimously by the Board in January.

The MWRD has long been known for its questionable financial practices and overall lack of transparency; the highest-profile example was the resignation two years ago of executive director David St. Pierre, who received a $95,000 payout as part of an investigation that is still not public; the Weekly is currently in the process of an appeal of the MWRD’s denial of a public records request relating to St. Pierre’s firing. With the new independent inspector general—and a new ethics ordinance as a result—the MWRD is finally taking a few steps to change that reputation.

Sam Joyce is the nature editor and a managing editor of the Weekly. He last covered the closure of Pullman café bakery ‘Laine’s Bake Shop and an exhibit of macro-photography at a Kenwood church for the Weekly’s Arts Issue.