This article was produced in partnership with the nonprofit newsroom Type Investigations, with support from the Puffin Foundation and the Wayne Barrett Project.

On September 23, thousands of ShotSpotter sensors that have been monitoring city streets for gunfire on Chicago’s South and West Sides stopped providing alerts to the police department — at least for now. The shutdown follows a monthslong fight between Mayor Brandon Johnson and members of the City Council over the effectiveness of the technology, and the mayor’s decision not to renew the company’s contract.

ShotSpotter’s supporters have argued that the technology helps police respond more effectively to gun violence, and may even save lives. But ShotSpotter has routinely failed to detect shootings in its coverage area, according to an analysis by the Weekly and Type Investigations.

ShotSpotter sensors detect loud noises that are then analyzed via computer algorithm and human analysts to determine if they’re gunshots. ShotSpotter’s parent company, SoundThinking, promotes its technology as highly accurate and promises to meet a certain threshold of performance to cities who agree to pilot programs or contracts. Chicago’s contract required ShotSpotter sensors to detect at least 90% of outdoor, unsuppressed gunfire above a .25 caliber.

An analysis of public data by the Weekly and Type Investigations indicates that ShotSpotter did not alert Chicago police to more than 20% of the shootings and reckless firearm discharges that occurred within its coverage area between January 2023 and August 2024, however, which raises questions about how well the company fulfilled its contractual obligations. That includes at least 180 gun homicides, as well as more than 600 nonfatal shootings and more than 400 reckless firearm discharges that ShotSpotter apparently failed to alert police to.

Some of these incidents could have involved small-caliber or suppressed (or “silenced”) gunfire—but it doesn’t seem likely. Suppressors are rarely used in criminal shootings. And while handguns are used in the overwhelming majority of shootings in Chicago, handguns below a .25 caliber are rarely traced to gun crimes.

ShotSpotter sensors are currently deployed in roughly 170 cities and 19 university and corporate campuses across the country and the world, according to the company’s most recent annual filing with the US Securities and Exchange Commission. Its listening devices—essentially microphones outfitted atop poles and rooftops—blanket more than 1,100 square miles of cityscape, including areas of New York, Denver and San Francisco. The Chicago police department and SoundThinking have repeatedly claimed the sensors detect more than 97% of gunfire.

SoundThinking’s vice president of corporate development, Gary Bunyard, agreed to an interview for this story, but backed out at the last minute, citing an unforeseen scheduling conflict. After reviewing the findings of the analysis by the Weekly and Type Investigations, a SoundThinking spokesperson did not offer an explanation for why ShotSpotter’s sensors apparently failed to alert police to the shootings and reckless discharges.

“We are pleased to see the level of transparency being promoted by the CPD with the ShotSpotter data now available to the public,” the spokesperson wrote in an emailed statement.

To assess ShotSpotter’s effectiveness at alerting police to gun crimes, the Weekly and Type Investigations analyzed three sets of data from Chicago’s Violence Reduction Dashboard, which the Mayor’s Office uses to provide public access to real-time CPD data. The first dataset includes all crimes since 2001, and the second tracks every homicide and nonfatal shooting across the city from 2010 to the present. The third tracks all ShotSpotter alerts notifying police of possible gunfire since 2017.

All three datasets include latitude and longitude coordinates and timestamps. This allowed reporters to match ShotSpotter alerts to police data on gun crimes in districts covered by the company’s listening devices between January 2023 and August 2024.

In its ShotSpotter contracts, SoundThinking claims its technology can identify and locate at least 90% of gunshots above a .25 caliber without a suppressor that occur outdoors, to within 25 meters, or about 80 feet, in under 60 seconds. To be as exhaustive as possible, our analysis searched for ShotSpotter alerts within one half-mile and one hour of shootings confirmed by police. We excluded any shootings that happened indoors or inside of a vehicle, because ShotSpotter claims it is not designed to detect these kinds of gunshots. The public datasets do not indicate whether suppressors were used in shootings.

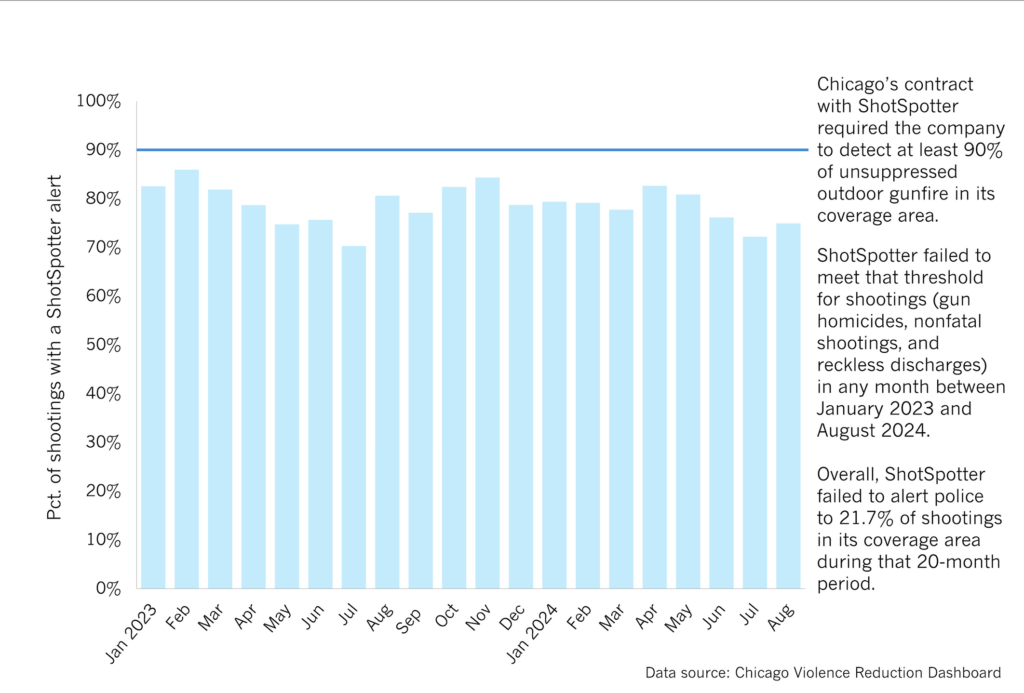

The Weekly and Type Investigations found that the percentage of reported gun crimes that had a ShotSpotter alert varied significantly across the seasons. But it never reached 90%, the contractually required threshold. The average detection rate over the 20-month period was about 78%.

In February 2023, a winter month when shootings are usually far lower, the detection rate was nearly 86%, the highest of any month we analyzed. In July 2023, a summer month when shootings typically peak, ShotSpotter alerted police to about 70% of all shootings in its coverage area, the lowest of any month we looked at. For homicides and nonfatal shootings, the average detection rate was 70% across the 20-month period.

In all of 2023, more than 100 fatal and nearly 400 nonfatal shootings in the coverage area had no ShotSpotter alert. Through August of this year, ShotSpotter has missed nearly 70 fatal and more than 250 nonfatal shootings in its coverage area.

One of the shootings took place on August 3 in the Back of the Yards neighborhood on the South Side. Around 6 p.m., two teenage boys were shot in a drive-by shooting. Although there were sensors in the area of the shooting, CPD had no corresponding alert. Both boys died from their wounds at a local hospital.

Records obtained from CPD align with our findings. At a September 18 press conference, 15th Ward Ald. Raymond Lopez (whose ward has 52 ShotSpotter sensors) announced that CPD had provided him with a report on shootings, ShotSpotter alerts, and associated 911 calls. Following a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request for those same records, CPD provided a spreadsheet listing every fatal and nonfatal shooting from January 1, 2023 to August 1, 2024 and indicating whether each had a corresponding ShotSpotter alert. According to CPD’s own data, 41% of fatal and nonfatal shootings in ShotSpotter’s coverage area during that time frame had no alert. A department spokesperson did not respond to questions about this data.

SoundThinking did not respond to questions about the seasonal differences in detection rates, or why the detection rate for homicides and nonfatal shootings was lower than the overall detection rate for all types of gunfire. The company claimed, without evidence, that it was not only meeting but exceeding its contractual obligations.

“Based on the feedback we receive from CPD regarding misses and mislocates, as well as the rigorous process SoundThinking follows to produce Monthly ShotSpotter Performance Scoreboards for each Chicago Police District we serve, we remain fully confident that ShotSpotter’s overall performance in Chicago consistently exceeds our service level commitments to the City,” the statement provided by the company read.

In 2023, CPD emailed ShotSpotter to report missed or mislocated shootings at least 575 times. Internal company emails obtained by the Weekly revealed Bunyard admitting the company missed a 55-round shooting in Back of the Yards in 2022 that wounded two men because nearby sensors weren’t working properly.

A common criticism of ShotSpotter has been that its sensors generate frequent false positives, which can lead to police wasting resources. A 2021 report by City’s Inspector General found that police recovered evidence of a gun-related criminal offense in fewer than 10% of the ShotSpotter alerts to which they responded. (In a blog post, SoundThinking alleged that ShotSpotter’s alerts are in themselves “digital” evidence of gun crimes, and said the report’s findings had been “twisted by a few critics to spread a false narrative” about the technology.)

During the 20-month period we analyzed, there were more than 70,000 ShotSpotter alerts. In ShotSpotter’s 12-police-district coverage area, there were more than 5,000 homicides, nonfatal shootings, and reckless firearm discharges that took place outdoors, according to the analysis of CPD data.

Not all cities have deemed ShotSpotter worth the price tag. Atlanta and Portland declined to sign long-term deals with the company, and San Diego, Dayton, and Charlotte decided not to renew their contracts after years of using the technology. ShotSpotter did not respond to questions about those cities’ decisions to cancel the contracts.

In 2024, the New York City Comptroller’s office released an audit which found that 87% of the time, when police responded to a ShotSpotter alert, they found no evidence of a shooting or could not confirm whether one had occurred. The office called on the New York Police Department to “reassess the performance of ShotSpotter, and its ability to detect shootings, before the contract is renewed.”

A SoundThinking spokesperson told the New York Times that the audit was “gravely misinformed in its assessment of data.”

In February, Johnson’s office announced he would fulfill a campaign promise to cancel ShotSpotter’s contract. But he ended up paying a premium to keep the system in place through the Democratic National Convention and, in the months since, faced intense pressure from the City Council to renege on his pledge.

Ald. Desmon Yancy (5th Ward), whose ward has 81 ShotSpotter sensors, voted in favor of 17th Ward Ald. David Moore’s ordinance that would attempt to force the mayor to keep the system. Yancy told the Weekly and Type Investigations that gunshot detection technology benefits the city, even if it “isn’t the end all, be all” to gun-violence prevention.

“It’s an investigative tool that triggers other tools, like POD [Police Observation Device] cameras and license plate readers, which assist police in their investigations,” he said in a written statement. “The police use this technology, along with community policing, and violence intervention organizations as a part of an ecosystem to keep communities safe.”

ShotSpotter’s advocates say the technology saves lives. At a public meeting in February, Remis Herrera, a community member, advocated for expanding the use of the technology, claiming that her brother’s life might have been saved had a ShotSpotter sensor been installed nearby to alert the police near instantaneously when he was shot.

“If this technology can save someone’s life, how can we quantify a person’s life?” she asked.

Ald. Andre Vasquez (40th Ward), who voted against Moore’s ordinance, effectively supporting Johnson’s cancellation of the contract, gave an impassioned speech at the Council meeting. He said he lost a friend to gun violence but thought SoundThinking had not done enough to prove ShotSpotter’s value.

Records obtained by the Weekly and Type Investigations via a FOIA request show that instances of life-saving police aid resulting solely from a ShotSpotter alert are few and far between. Between December 2020 and May 2024, ShotSpotter alerted police to 498 gunshot victims to whom they rendered aid. Just 30 cases had no corresponding 911 call.

Critics of ShotSpotter claim that, rather than saving lives, the technology leads to over-policing in the neighborhoods where it’s deployed, priming police for a potentially violent response. In 2021, police, responding to a ShotSpotter alert, killed 13-year-old Adam Toledo in the Little Village neighborhood as he was surrendering to police.

Ald. Byron Sigcho-Lopez (25th Ward), who represents the ward where Toledo was killed, voted against Moore’s ordinance.

In an interview, Sigcho-Lopez was adamant that the technology contributes to the over-policing of poorer communities of color and discriminatory policing practices such as stop-and-frisk. He said it has been difficult to reconcile the conflicting accounts about the technology from the OIG’s report and academic studies with the opposing messages and briefs put out by the company and CPD.

“How are we going to rely on the data of the software company that is trying to sell us a contract?” he said. “There is a clear conflict of interest.”

He said that ShotSpotter “is not a good replacement” for 911 calls.

“We need to distinguish and invest in what we know works,” he said.

Nat Palmer, an activist with the Stop ShotSpotter campaign, said that their main objection to ShotSpotter is that it attempts to address violence through surveillance, rather than by alleviating its root causes. But they said that millions of dollars a year for a technology “that doesn’t even seem to work at a high percentage rate” seems like a poor use of the City’s financial resources. “It’s dangerous to continue to blindly throw money at things,” they said. Chicago is currently experiencing a massive budget shortfall.

Palmer said the City should consider investing that money in an alternative dispatch system for mental health and social services workers to respond to certain kinds of crisis calls. This alternative-to-police response is part of a larger movement called Treatment Not Trauma.

A CPD spokesperson did not respond to emailed questions.

The Mayor’s Office, which hosts the City’s Violence Reduction Dashboard on its website, and the Office of Public Safety Administration, which provides technical support to CPD, likewise did not respond to requests for comment.

On September 18, Johnson issued a scathing critique of ShotSpotter, promising to veto Moore’s ordinance that would have allowed CPD Superintendent Larry Snelling to sign a new contract with SoundThinking.

“When this was brought before the people of Chicago, this is what they were told, that it would reduce violence and it would lead to more arrests. It’s done neither,” Johnson said at a press conference. “It’s an ineffective tool and I’m not going to allow the interests and the greed of a corporation to play on the fears and anxiety of the people of Chicago.” Johnson walked back his promise to veto the ordinance late yesterday; A spokesperson told WBEZ the veto was “deemed unnecessary.”

SoundThinking representatives have said the company will work with Chicago police over the next several weeks to ensure the transition is smooth, and that the company has begun “prioritizing and de-installing ShotSpotter sensors on public-owned infrastructure throughout the 12 police districts being served.”

But a reprieve is still possible. Hours before ShotSpotter’s sensors began to go offline, the Mayor’s Office announced that the city is looking for “law enforcement response” technology that can detect incidents with 95% accuracy, in order to assist police and other emergency personnel.

SoundThinking has indicated that it plans to apply.

Update, December 19, 2024: After this story was published, an attorney for SoundThinking contacted the Weekly to request that the following statement be added:

“By all metrics, ShotSpotter is an effective tool for detecting gunfire and alerting police to gun crimes. But Chicagoans need not take our word for it; the Chicago Police Department publicizes its own data on ShotSpotter’s success in detecting gunfire in the city, and that data shows that ShotSpotter has met and far exceeded its contractual commitments to the city of Chicago to detect at least 90% of all outdoor, unsupressed [sic] gun discharges for rounds higher than .25 caliber. The company believes that South Side Weekly’s assessment is based on highly selective and misleading underlying data that does not reflect the actual criteria the city of Chicago set for assessing ShotSpotter’s efficacy. It is telling that CPD has never once found that ShotSpotter failed to meet its contractual commitments, even though the city had a direct financial incentive under its contract with SoundThinking to do so. SoundThinking is proud of ShotSpotter’s performance in the city of Chicago and beyond.”

Max Blaisdell is a fellow with the Invisible Institute and a staff writer for the Hyde Park Herald. Ethan Corey is The Appeal’s Research & Projects Editor. Jim Daley is the Weekly’s investigations editor.