We have so many millennia of information recorded in our frickin’ DNA, and all it takes is the right time and place to trigger it,” says saxophonist Isaiah Collier. “Something like that happens for me sonically.”

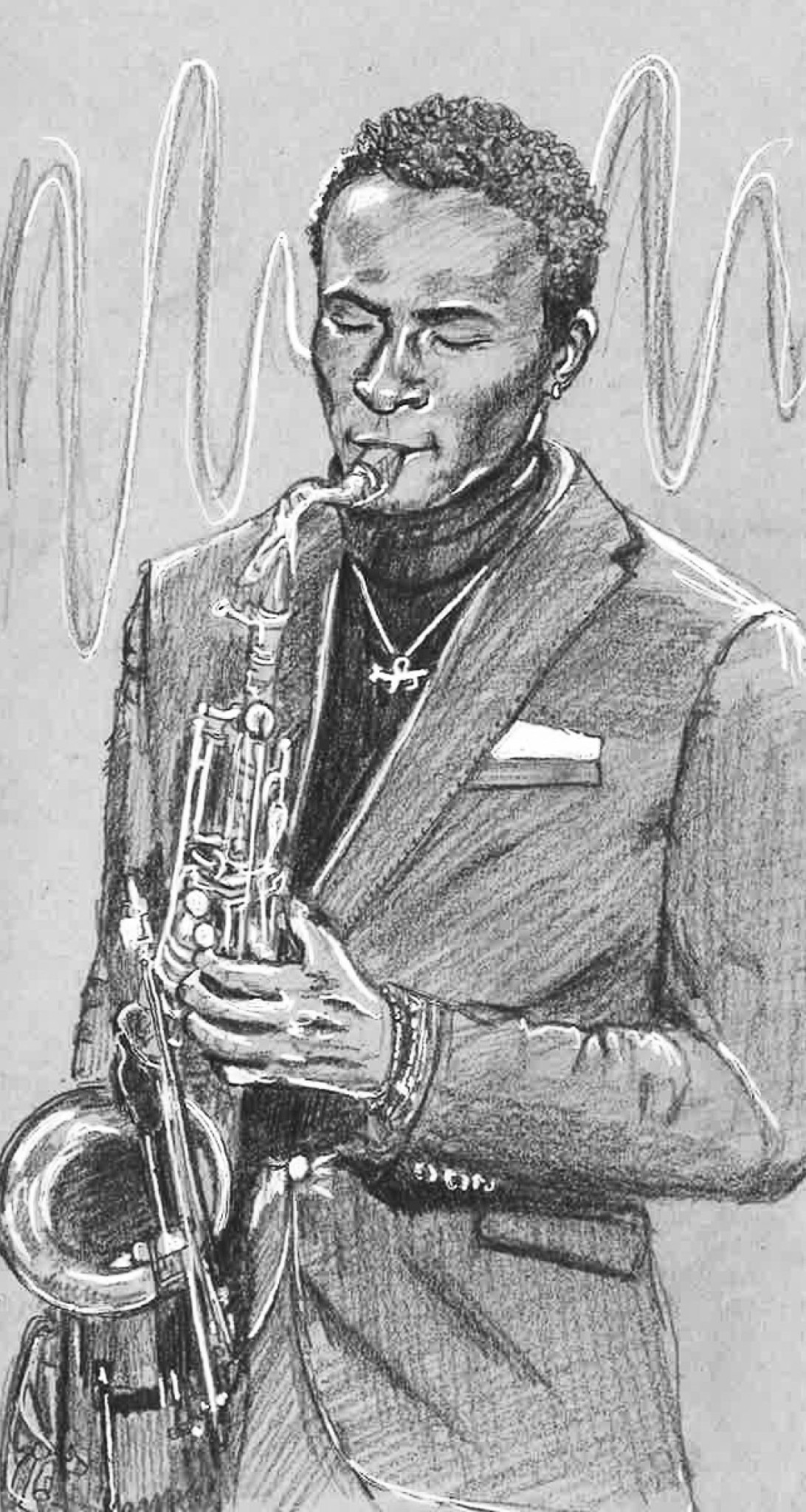

At twenty, Collier has already shared a stage with Chance the Rapper and appeared at jazz festivals across the world. These accolades make his disarming charm and unassuming composure all the more striking. I sat down with him a few weeks ago to discuss his musical philosophy over a plate of sushi. Under the looping choruses of Top 40 hits, we talked about everything from genetics to folk music.

Collier’s roots in the Chicago jazz scene run deep. A Park Manor resident and a graduate of the Jazz Institute of Chicago, he recently returned to his hometown after spending a few years at the Brubeck Institute in Stockton, California. Mentorship by local giants like Willie Pickens and James Perkins Jr. has given way to performances with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and, most recently, with his own band, The Chosen Few.

But Collier’s introduction to the world of jazz had a decidedly humbler tone. Less than a decade ago, a flyer for a music camp caught in a Chicago breeze landed fortuitously in his mother’s face, giving him his first shot at the saxophone. Years went by and his passion grew. His father, a keyboardist and singer, would bring a twelve-year-old Collier to play along at gigs. “And I was like, ‘Oh crap! I made twenty bucks doing that!’ But it really put some perspective on it,” Collier said. He remembers thinking, “Wait, I can actually make some money doing this?” Soon, Collier would be playing for his local church, reviving the classic R&B tunes he heard as a child for new audiences.

Collier discovered the philosophy behind jazz from an unlikely source. “I was hanging out with one of my dad’s friends who was trying to help me improvise, and he told me, “Learn how to play ‘Happy Birthday!’” Collier exclaimed, “Anyone can play a song, but it doesn’t speak, have meaning… It’s all about making it yours. If everyone is saying the same thing, then you’ve got a problem.”

From there, his musical career grew, taking him to jazz festivals from Hyde Park to California. It culminated in the formation of his band, Isaiah Collier and the Chosen Few. In 2017, the group independently released its first album, Return of the Black Emperor. The haunting ballad “I Am Who I Be” lines up next to the seismic bursts of “War Song” and the evocative wails of “Mali,” each displaying Collier’s versatile style. But it is the title song, “Return of the Black Emperor,” that demonstrates the heart of Collier’s approach to his craft.

On one level, the listener hears an assured conversation with the legends of saxophone as he channels the creative force of John Coltrane and Wayne Shorter. But Collier doesn’t aim to mimic these giants of the genre. “It’s a dialect I understand,” he commented, “Like, when I think about Charlie Parker and all these cats, I’m not thinking about sounding like them: it’s a style. You’ve gotta be vulnerable enough to put yourself out there.” Instead, he injects his interests—from Mayan folk music to flamenco—into the picture.

As he describes it, music, like déjà vu, activates something buried in his subconscious. “I think it really just comes down to a genetic thing. Part of you has been somewhere that made this kind of music.” Collier is fascinated by how genetics, history, and music might operate in tandem. Jazz, like hip-hop, relies on excavating the rhythms and chords latent in our cultures and retrofitting them to speak to present concerns. “It’s weird,” he pondered, “it’s like we’re reaching backward and forward at the same time.”

In an era when opportunities for young artists are shrinking as clubs shut their doors, school arts budgets are cut, and record companies pursue algorithmically-crafted pop progressions for the mass market, Collier is trying his hand at preserving accessible jazz education for kids.

He’s conducted master classes at Chicago High School for the Arts and at several schools on the South Side, and has been involved with the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) of Chicago. “It’s in [kids’] blood; they don’t know unless they try,” Collier said. “And there are so many different versions of themselves, but they need to have an example.”

In his eyes, the perpetual struggle of the Black community in America has motivated near-continuous bursts of artistic innovation that have snowballed over time. Jazz embodies that legacy. “If you wanna talk about jazz, we gotta start further than that, with gospel, and if you wanna talk about that, then we gotta start with the blues, and for that, we’ve gotta talk about ragtime, and the Negro spirituals. It’s like we’re telling [all those stories] at once,” Collier told me with a smile. “It’s the message of the ancestors, man.”

And those ancestors speak loud and clear in every chord, blues progression, and vocal harmony. “We have to stress the history. I try to make sure that the children know that. I’m telling you to know your history. Because that’s what makes jazz so unique. It’s tailor-made for everybody who plays it. Any of us can come from different perspectives on it, and that’s what makes it so infinite.”

As we spoke, Collier reflected on how one of his mentors, James Perkins Jr., once inquired about his algebra skills. “And I would wonder why he was asking me this,” Collier mused, “And he’d say, ‘There’s no difference.’” His confusion, he remembered, soon gave way to epiphany. “They’re all utilizing the same type of properties. Music is just a sonic version of chemistry. It’s a giant painting, in a museum we can all visit.”

Towards the end of our conversation, Collier showed me an image on his phone. Mistaking the star-shaped drawing for some kind of Da Vinci diagram, I asked him what it meant. “It’s John Coltrane’s spiritual geometry,” he said, “his Circle of Fifths, for ‘A Love Supreme.’” Considering that pentagram, with its intricate lines producing an eerie symmetry, I felt the gravity of Collier’s words on jazz. Mathematics, science, music—glued together through the sheer force of belief. Sonic chemistry, indeed.

Krishna S. Kulkarni is a Master’s student at the University of Chicago, where he studies Middle Eastern history. He writes about food, music, and the people who craft them. He lives in Kenwood.