This story was co-published with the Hyde Park Herald.

Stoopin’ with Lloyd Brodnax King on a mild Monday in May, his Bronzeville block of gingerbread houses seems bucolic and secluded.

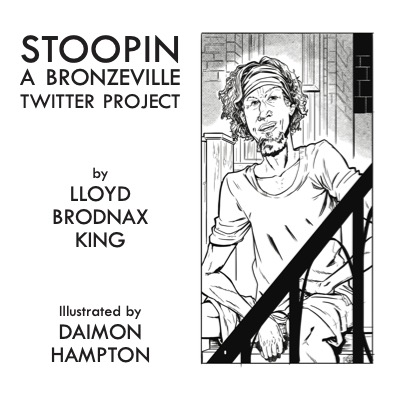

Sitting on his porch, his curly gray hair perpetually held up by a bandana, King showed me the vistas of Berkeley Avenue and 41st Place, streets that once played host to the action-packed scenes from his book Stoopin: A Bronzeville Twitter Project.

Stoopin is an assemblage of tweets King, a teacher, musician, and multimedia artist, wrote from 2010–2017. They depict slices of life on a rapidly gentrifying block. Often these vignettes are urban curiosities and feats of skill or wit:

6/19/11

Stoopin. Man walks pit bull off leash, holds a 40 in a paper bag. Dog runs ahead. Chases cat. Man follows. Bad dog! BAD! Grabs pit bull without spilling a drop. Carries both home.

Looking around, I have to ask “ubi sunt,” or “where are they now,” about the heroes of King’s book. Just as I am hearing about Bogdan and the gut renovations, the suit served on Willie after Babs moved, a man in a loud kente cloth coat comes up that quiet street.

“Well, this is Lionel, who was here during the Stoopin years, grew up here,” King said. “What’s up, Brother El?”

Lionel and King barter over candy, coffee beans, and homemade hummus. Lionel, it’s explained, is one of the few young people from the Stoopin years still around the neighborhood. Invitations are exchanged: Brother El has an upcoming “Sandbox Symphony” at Oak Street Beach, and King is once again planning a Juneteenth block party and concert.

Street life continues, despite my initial impression.

The book was published in 2022 by It Came From Beyond Pulp, a small sci-fi and fantasy book press run out of a basement in Hyde Park, with illustrations by local comics artist Daimon Hampton.

Assembled by editor and publisher Mike Phillips, it is a little “Iliad” (or “Omeros”) of an intersection in Bronzeville. King’s tweets (now verses of this narrative poem) capture the moments of ambiguity between beauty and terror, between violence and joy, giving glimpses of what life meant at a certain place and time with densely packed intensity. King’s watchword in his various projects is the search for the “beautiful, shocking, and awe-inspiring.”

Sometimes the images are mysterious:

7/19/10

Stoopin. Kids find a zebra-striped suitcase. Zip a kid in, all but his arm.

Screams. Let him out. But it’s fun. Count to 10, then let him out. Next?

7/19/10

Stoopin. Kids zooming down 41st with a zebra-striped suitcase in tow. A

muffled scream comes from inside.

7/20/10

Stoopin. The zooming suitcase stops. 10… 9… 8… unzips. Kid is freed.

Dazed. Will he ever be the same?

Violence is often ambiguously suggested by children’s play, as when some kids grabbed “weapons” (sticks). But they are soon seen marching home, “heads hung against the weather… We was gettin tough, then it started raining.”

And it is conjured or averted in the stupid games of adults as well:

2/11/11

Stoopin. Argument escalates. Big dude takes off shirt. Let’s box! Small dude pulls down pants and waves cock. Aw man, put that back! Fight over.

The book records heroes of old, most vivid in the saga of D’Angelo, a “church boy with a mohawk.” Most dramatically, he emerges as a protector, when one day (while stoopin’, of course) King saw:

Junior thugs beating down a kid. D’Angelo, babysitting, leaves his charges and rescues the kid. Thugs turn on D, who grabs his toddlers, one in each arm, and splits!

D’Angelo returns, with “a chain wrapped around his hand,” but soon becomes the victim of police attention. Cops begin to taunt him; one does a “sissy walk.” But King, stoopin’, perceives that here “D is Shane. Or Milk.” King told me that D’Angelo eventually went to Lincoln University, an HBCU in Missouri, to study forensic science, but was shot and killed in 2018 under unclear circumstances.

King’s house occupies a perch on a T-shaped intersection, with a sight line down Berkeley toward the busier 43rd Street, as well as views of the lakefront and Lake Park Ave. There are parks both ways, an alley and stoops or decks on three sides of King’s house, making the whole thing a complex deer stand for urban reality, or “the action,” as King calls it.

From his rear deck you can see the old Kenwood rail tracks, the blue pedestrian bridge at 41st Street, and the lake. On the other side, a porch floats amid the abstract wooden sculptures of the Oakland Museum of Contemporary Art, which the late Milton Mizenberg carved with a chainsaw to invest the immediate neighborhood with visible cultural wealth and give a boost to the block during tough times. “This sculpture is dedicated to the men and women who remained in the Oakland community during difficult times and worked hard to restore its former beauty,” an inscription on one sculpture reads. King, also a musician, used to jam with his neighbor Mizenberg, and found out eventually that the city considered one of the lots making up the museum part of King’s property. He has since become a custodian for some of the pieces.

King has the requisite sense of utopia and urban engineering. He mused about his childhood fascination with the sci-fi domes of space age designer and futurist Buckminster Fuller when I said I was from Carbondale, where Fuller lived and worked. This patch of the South Side could be viewed as an experimental utopian operation itself.

The block was designed by architect and builder Cicero Hine in the 1880s and attracted elites of Chicago’s business and legal communities. Now, in the pandemic, King has built a stage on the north side of the house, overlooking Mizenberg’s sculptures. It served as practice rental space for bands who could not get together indoors pre-vaccine, and it will be the mainstage for his upcoming Juneteenth block party.

King described the vibe of his block’s summer gathering in a nearby vacant lot as a “Sesame Street.” “It’s so interracial and everyone brings a quart of…something.”

Though he plays an active role in the life of his neighborhood, in Stoopin, King is a narrator whose character only comes through in his observations of others,

7/30/10

Stoopin. Holy shit. A motorcycle gang in front of realtor John’s. Leather and studs. Turquoise gas tank. John in a black bandana flashes the peace sign.

what he notices around him,

5/14/11

Stoopin. Ofrenda for the kid who was shot in the head last week. Candles. Flowers. Teddy bears. Scrawled: RIP Tim, love A-L. Box of Thin Mints.

and what he brings out in the interactions he records.

6/20/11

Stoopin. Mercedes. Cruising. Slowly. Is that an 11-year-old driving? Kid blushes. Man in passenger seat says, gotta teach him how.

There is a rich tradition of this kind of urban bard, and in fact, King said that Chicago’s immortal storyteller and broadcaster Studs Terkel taught him how to make a vodka martini as a kid.

This Studsian approach was carried through King’s projects in radio and music education. King said his parents were Marxists, or at least his father was enough of a Black nationalist that he would support “the devil if he was going to do something for Black people,” which at the time meant the Communist Party. This left King with a sense of wanting to control the “means of production,” which for him have been the technologies and practices of music, radio, and sound.

His path from musician to scribe (he was trained on jazz flute) led him to becoming an early adopter of the podcast. In 2007, King was a relatively successful performer gigging weddings and bar mitzvahs, and thought he could take his extensive knowledge of music production into the podcast world.

So he did. He began a project called The Obscure News, which featured slice-of-life interviews he conducted in unconventional places, trying to let individuals shine in a light that balanced everyman universality and off-the-wall unpredictability.

The program was ahead of its time in terms of production value, creative editing, and mastery of the audio format for a podcast. “I know sound,” King said. This led to his being brought on as content director for Vocalo, Chicago Public Media’s urban alternative radio.

Despite King’s being a self-described luddite, attached to old, analog technology like bikes and radio, the #Stoopin project emerged on Twitter in the summer of 2010. He had learned to use the platform during his time at Vocalo, and when he and his wife first moved to Bronzeville, they made an end-of-day ritual of cocktails on the front porch while she did the New York Times crossword. This left him free to apply the observational style of The Obscure News on a new platform.

From King’s back deck, we can see the Williams-Davis Park, formerly known as Park No. 532:

9/29/11

Stoopin. Park 532 naming controversy continues. Dead Scrappy Activist’s people vs. Dead Super PTA Mom. Activist’s folks tell moving stories. PTA Mom’s folks say, If we don’t win, we’ll sue.

Eventually it got the hyphenated name. Also visible is the berm of the former Kenwood train line, soon to be a 606-style walking trail for the South Side. Neighborhood change was apparent in the book. At the start, there’s some resistance:

8/29/11

Stoopin. Bloods move out. Neighbors relieved. Rehabbers come. Drywall. Nice doors. Security cams. Bloods return! What, they couldn’t flip it?

When he first moved to the neighborhood, King was told his house was apparently a drug den in the nineties. His bandmate’s car’s radiator was once riddled with bullets during a practice. The week King moved to the block, he opened the door to receive a pizza delivery and saw a shooting and police foot chase.

King and his wife moved to Bronzeville when she quit her job as dean at a north suburban college. When she planned to quit her job, King said he told her, “Okay honey, but if you quit, we are moving to the city. And we are moving to an all-Black neighborhood, where racism is going to get us a lake view.”

Toward the end of Stoopin, a “perky flipper” who doesn’t even know she’s in Oakland becomes a recurring character. The Black cowboys of Chicago’s Broken Arrow Horseback Riding Club, founded thirty years ago by a South Sider known only as Murdock, also emerge. The cowboys, more recently in the spotlight since the summer of Old Town Road and protests throughout 2020, show up as a defensive brigade on the day of Trump’s inauguration, evocatively drawn by illustrator Hampton. The era of Stoopin’s denouement and the transition from the lost recent past to our present day is also heralded by the arrival of U-Hauls and joggers in Lululemon traversing the block.

Now, things have moved on, but King’s book stands as a testament to what came before, a witty lament.

Maybe if I had to create a #Stoopin tweet to narrate my own visit, it would go:

#Stoopin. Hyde Park white boy rolls up to see the scene. He doesn’t know, the scene’s been scawn.

Lloyd Brodnax King, Stoopin: A Bronzeville Twitter Project. $13. It Came From Beyond Pulp. 27 pages.

Benjamin Ginzky is a law student at Chicago-Kent and lives in Hyde Park, where he is a docent at the Oriental Institute and involved with the 57th Street Meeting of Friends. He also edits nonfiction at Mouse Magazine. He last wrote for the Weekly about the roots of Sun Ra’s career in mid-century Chicago.