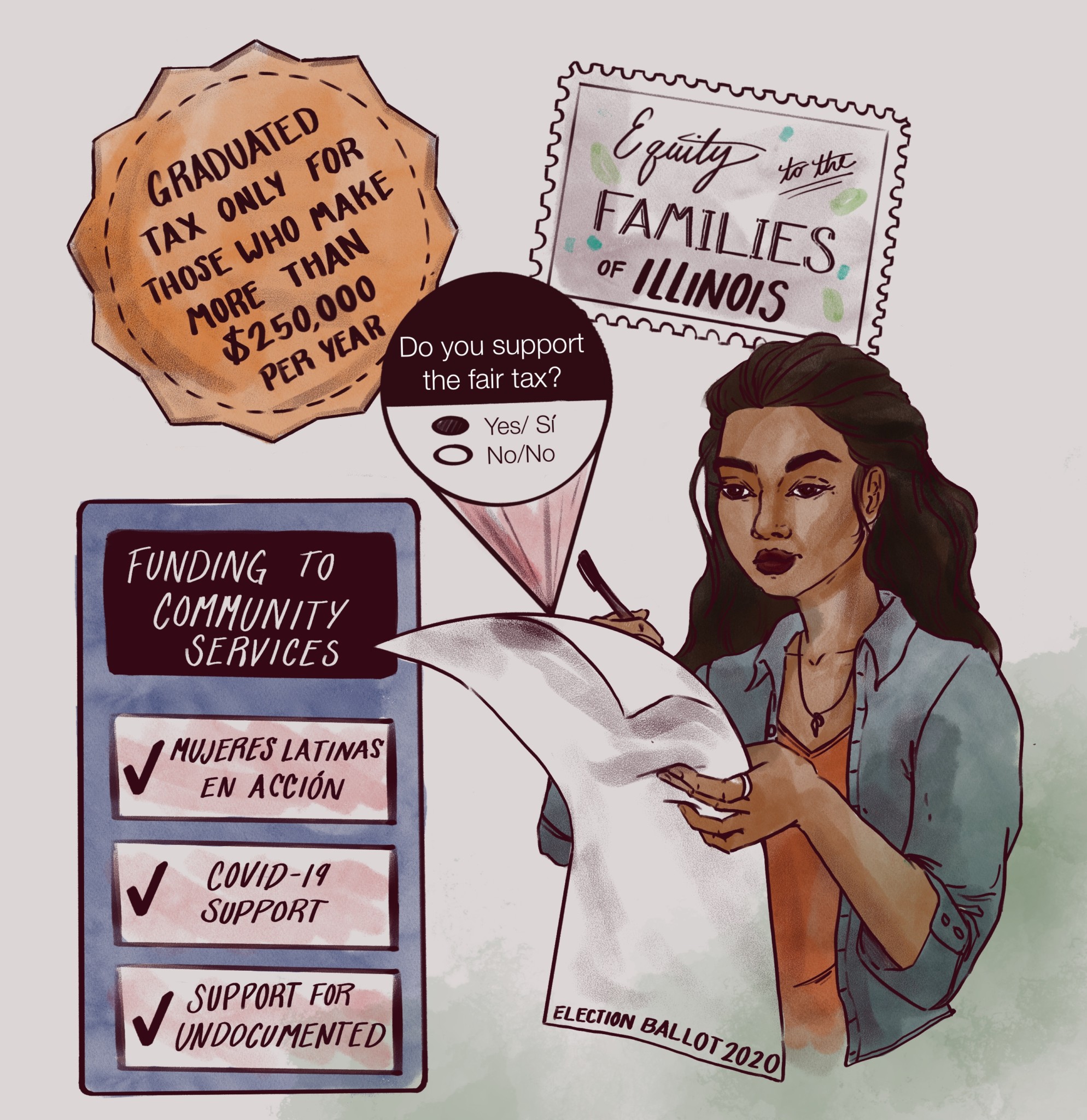

Voting is underway in Illinois, with voters deciding “yes” or “no” on whether to amend the state constitution to allow a graduated income tax. It would make effective proposed legislation to replace the current flat-rate tax system with graduated rates.

For twenty years, María Guadalupe Acevedo has lived in Gage Park on Chicago’s Southwest Side. She has two sons who are now in their twenties and has been divorced for nearly two years; she currently lives alone. Acevedo earns about $375 every two weeks working part-time cleaning a fitness center downtown. She said she has counted on state-funded programs from Mujeres Latinas en Acción, the longest-standing Latina-led community service organization in the nation, for support. There, she pursued her GED and accessed mental healthcare through Medicare.

Like most people in Illinois, Acevedo has heard the advertisements circulating on the airwaves about Governor J.B. Pritzker’s proposed move to a graduated income tax. Ads that oppose the graduated income tax amendment say it will open the door for higher taxes on the middle class and hurt small businesses. Those who support it emphasize it will only raise taxes on the wealthiest Illinoisians—millionaires and billionaires. The Pritzker administration estimates that ninety-seven percent of Illinoisans will see at least a modest decrease in income taxes if the constitutional change passes.

Acevedo doesn’t trust what she hears via political advertisements without doing her own research, so she searched for information online to get behind the buzz. “From what I read, the fair tax is a tax where everyone will pay their taxes. To me this seems fair,” Acevedo said in Spanish. “Right now, we who make less have to pay more.”

Because Illinois has had a flat-rate tax system since 1970, taxpayers like Acevedo pay 4.95 percent of their income in taxes, as does everyone else in the state, including billionaires. But for Illinoisans with less disposable income, that’s a greater portion of their income needed to afford the cost of living, said Lisa Christensen Gee, director of special initiatives with the liberal-leaning Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP).

“That’s what we call a regressive tax system, one that asks people with less money to pay a higher share of their income in taxes than those with more money,” she said. This regressive tax system is a fixture of the state constitution, which currently requires that all taxes on income be at the same rate.

Voters are not deciding on rates themselves, but the specific rates proposed by Pritzker would raise taxes only on people who earn $250,000 or more a year—incomes between $250,000 and $500,000 would be taxed at 7.75 percent. “The amendment does not itself change tax rates. It gives the state the ability to impose higher tax rates on those with higher income levels and lower income tax rates on those with middle or lower income levels,” voters will read via language on the ballot.

On every Illinois ballot, a notice lets voters know that failure to vote is the equivalent of a negative vote, and that the amendment will become effective if approved by either three-fifths of those voting on the question or a majority of those voting in the election.

Grassroots Collaborative has been active in reaching out to voters to advocate for the graduated income tax. Executive director Amisha Patel said at this point in the election, that often means sifting through the contradictory messages reaching voters on the ballot question. With commercials flooding TV, radio, and online spaces, voters have a lot to sift through.

The loud messaging over the proposed amendment has come from heavy funders both in favor of and opposed to the amendment. Pritzker donated $56.5 million of his own fortune to the “Vote Yes for Fairness” political committee. Ken Griffin, the state’s richest man, and also the face of the effort to stop the graduated income tax, has personally donated more than $46 million to stop the proposed amendment.

Calling the amendment “catastrophic,” Griffin said in a statement, “every citizen has a right to the truth about what Governor Pritzker and [state House Speaker] Mike Madigan’s tax increase will mean for our state: the continued exodus of families and businesses, loss of jobs and inevitably higher taxes on everyone.”

Patel scoffed at the claim of a tax-induced exodus of Illinois’ uber-wealthy. “It’s a scare tactic to say rich people are going to leave. Where are they going? Almost every state around us has this tax code,” she said.

Right-leaning think tank Illinois Policy Institute filed a lawsuit against Illinois Secretary of State Jesse White and members of the state Board of Elections on October 5 saying a pamphlet released by White contains “misleading statements” around the proposed amendment. They allege that the graduated income tax amendment would make a tax on retirement income more likely, which proponents of the amendment say is not true.

“We know the impact is to confuse people, to spread disinformation, to spread fear,” Patel said.

ITEP goes so far as to call the state’s flat income tax a “tax subsidy for the wealthiest Illinoisans that compounds income and wealth inequalities,” and one which exacerbates the racial wealth gaps in the state and Chicago.

ITEP completed a retrospective analysis in September where they applied a graduated income tax to the last twenty years in Illinois. “Under the same distribution of the Fair Tax, the wealthiest three percent of Illinoisans would have paid on average an additional eight percent of total income taxes or $27 billion from 1999-2019,” the analysis read.

The analysis also found that Black and Latinx Illinois taxpayers with taxable incomes less than $250,000 would pay $4 billion more in taxes over the twenty-year period studied under a flat tax than they would under the Fair Tax in the retrospective analysis.

“This choice of tax structure, the flat income tax versus fair income tax, also makes these wealth gaps even worse,” Christensen Gee said.

Looking backward also meant considering the way the state handled its budget when it bottomed out during the 2008 recession—cuts to jobs and social services. This is the “nightmare scenario” that Pritzker has warned may happen without federal assistance or any new source of revenue. He said thousands of people could be laid off, worsening an economic recession and reducing funds for much-needed social services. Pritzker’s administration estimates that the graduated income tax may bring in an additional $3.4 billion a year.

The proposed amendment was in the works before COVID-19, but as the state scrambles to recover, Christensen Gee said it couldn’t come at a better time.

“If we only have a lever that says we have to turn up the tax requirements on everybody or no one, that puts us in a horrible position to respond to this moment in a way that actually accomplishes our goals, which is to ensure we have a public health infrastructure, ensure we have public schools available, ensure that we have the means whereby people can travel to see family and for essential workers to get to the job,” Christensen Gee said. “It compromises our ability to build the society we want if we only have one level that says everybody up or everybody down, and it just doesn’t mirror what we see in the world.”

If the proposed amendment doesn’t pass, it could also mean cuts to services such as those Mujeres Latinas en Acción provides to survivors of gender-based violence and sexual assault. The organization receives $2 million in state funding to provide support to Latina women in Southwest Side neighborhoods in Chicago.

Monica Paulson is the government grants manager at Mujeres Latinas en Acción. She says the organization is at risk of losing funding from the state if cuts are on the horizon.

“The state is in a tough situation because of the pandemic, and we really need the fair tax to help us get through that so we can keep providing these services,” Paulson said. “The COVID-19 pandemic has led to an increased vulnerability for immigrant and Latina survivors and it is critical we maintain services like crisis intervention and counseling which are crucial to their healing.”

Paulson also noted how critical it is for undocumented immigrants in the communities she serves to have an opportunity to receive services at a time when federal benefits are out of reach to alleviate loss of employment and accumulating debts.

Mujeres Latinas en Acción has conducted several needs surveys since the start of the pandemic to gauge the economic impact of COVID-19. Its August survey found that sixty-nine percent of respondents had their employment impacted, and seventy-four percent of households suffered income loss. Of the 785 community members who participated in the survey, sixty-four percent are ineligible for unemployment insurance and federal stimulus checks.

“Often undocumented people are being disproportionately impacted by things like the COVID-19 pandemic and yet they’re not seeing their tax dollars supporting them and their communities,” Paulson said. ITEP found that collectively, undocumented immigrants paid an estimated total of $10.6 billion in state and local taxes in 2010. But programs available to undocumented people for relief during COVID-19 have mostly relied on philanthropic or community-raised mutual aid funds.

This year has been one of political awakening and empowerment for Latinx voters like Acevedo. Though she has never contributed to a political campaign, she has felt emboldened through Mujeres Latinas en Acción to contribute her voice, and to share her stories and experiences on standing up against racism and the dangers of firearms.

It is also why she will vote yes for the fair tax amendment this November. For Acevedo, it isn’t just about taxes, it’s about a more equitable future she wants for all Illinois families. One in which, in her words, “it’s not just that some of us pay and others don’t.”

This report was produced by City Bureau, a civic journalism lab based in Bronzeville. Learn more and get involved at citybureau.org.

Alexandra Arriaga is a City Bureau reporting resident based in Pilsen. Her reporting focuses on how immigrant communities in Chicago build power and participate in democracy. She last wrote for the Weekly about Chicago’s climate apartheid.

My problem with the amendment is there is no wording in it that requires the legislature to change tax rates in the way proponents say they will. It gives them carte blanche to do whatever they want to. Wife & I will be voting no.