2700 South State Street was once an anchor in a lively network of saloons, cafés, and vaudeville houses, as well as Chicago’s first major home for African-American theater. The Pekin Theater, as Thomas Bauman writes in his new history of the venue, was “engulfed” by the Dearborn Homes in 1946 and demolished in 1952. But until then it was a cultural icon on the stretch of State Street from 26th to 39th once known as “the Stroll,” and Bauman’s book reflects that rich history.

The Pekin: The Rise and Fall of Chicago’s First Black-Owned Theater is structured around the life of one Robert T. Motts, who founded the theater and served as its executive director from its opening in 1904 until his death in 1911. As director of the theater, which offered some of the best and most comfortable outfitted entertainments on the Stroll, Motts was a leading figure in Chicago’s African-American cultural scene. “The political and social uses to which he put his wealth and influence carried a distinct element of racial consciousness and commitment,” Bauman writes. A former gambler and saloon owner, Motts was determined to develop the Pekin, as he put it, into “a playhouse worthy of the name and a credit to the Negro race.” When he died, “four thousand mourners, black and white,” showed up for his funeral.

One of the most impressive things about The Pekin is how much Bauman manages to reconstruct from so few remaining primary sources. As Bauman informs us, “No scripts, sound recordings, or archival records from the Pekin have survived.” Instead, he relies heavily on (often lively) write-ups in “black weeklies and white dailies,” as well as other sources which allow him to reconstruct an intricately detailed timeline of the Pekin’s history, including, it seems, nearly all the shows that played there and the actors and actresses who played in them. A particularly critical aspect of the theater’s history is the evolution its top-of-the-line stock company, which was, at one point or another, home to some of the first well-known African-American theatrical talent in the United States. Lawrence Chenault, Lottie Grady, and the beloved Harrison Stewart all had numerous runs on the Pekin stage. Nor was the Pekin wanting for musical talent: Joe Jordan, a celebrated composer of both ragtime and vocal anthems, spent time at the Pekin as a sort of composer-in-residence.

What is wanting in Bauman’s account is more information from about the character of the theater and its various players. The Pekin provides an exhaustive collection of facts, but this reviewer finds it difficult to imagine what it might have been like to attend a show there. The book is thorough in its details but lacking in imagination; by the time I finished it, I knew the birth and death dates, and the middle initials (Bauman is particularly meticulous about providing middle initials), of nearly everyone involved in the story of the Pekin, but I didn’t know much about what they were like as people. What did they say that was thought provoking? How did their contemporaries describe them? Bauman quotes a few surviving letters, but The Pekin would have benefited from some more exploration of the humanity behind the history.

Still, Bauman’s thorough knowledge as a musicologist is one of the highlights of the text. The few pages of sheet music that do survive are subjected to his thorough analysis, and I found it gratifying to read about the way that Joe Jordan subverted Mendelssohn’s “Wedding March” in his “artful” song “Lovie Joe.” Bauman places the Pekin’s African-American theatrical music within a distinct tradition and is fastidious in discussing the ways it interacted with the popular music of its era.

Beyond its details, The Pekin deserves praise for delivering this significant piece of history. Anyone who is interested in African-American theater, or even in the history of social consciousness and art in Chicago, can benefit from this clearly written and well-researched exploration of a nearly forgotten playhouse. We certainly wouldn’t have eta Creative Arts without the Pekin, or even many of the plays that have found a home at Court Theatre; we needed Chicago’s first black-owned and operated theater to give racially conscious plays a voice. Though its original purpose was simply high-quality entertainment, its existence was an important milestone, as Bauman reminds us. When vaudeville finally gave way, according to a 1911 article in the Chicago Defender, the Pekin played host to those first critical works of art with “a deeper and grander meaning.”

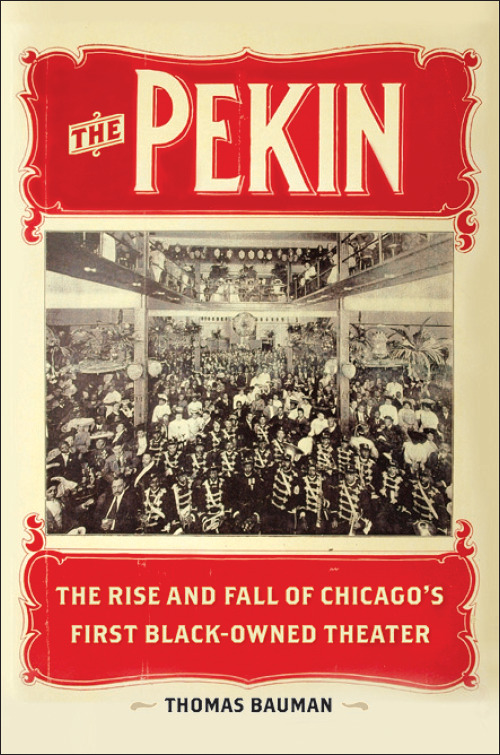

Thomas Bauman, The Pekin: The Rise and Fall of Chicago’s First Black-Owned Theater. University of Illinois Press. 264 pages.