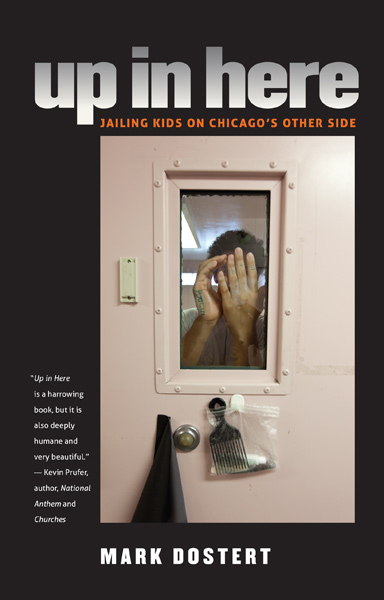

With Up in Here: Jailing Kids on Chicago’s Other Side, Mark Dostert returns to the detention center where he once volunteered as a student chaplain. Then, interpreting scripture for a cluster of quiet, studious residents came with a sense of duty and idealism. That idealism evaporates his first day on the job. As Dostert quickly realizes, the responsibilities of a “children’s attendant” are those of a jailor. He seems surprised and even offended by every detail of his job. He expected to serve as a kind of cell block counselor, mentoring young boys over games of chess on the value of impulse control while a real guard stood silently in the background. He is appalled at the way Audy Home supervisors run their show: “Children sanitizes the more accurate labels—juveniles or inmates—that we’re instructed not to call the boys…Sleeping in a room must not scar a boy’s soul compared to sleeping in a cell. Glancing into the rectangular brick-walled chambers, hardly wider than my arms’ span, I can’t deny that they are cells, damn it. And in cells live inmates.”

By his own admission, Mark Dostert is an outsider at the Cook County Department of Corrections. A native of suburban Dallas, and a graduate of the Moody Bible Institute with a Masters in early modern European history from the University of North Texas, Dostert was not an obvious choice for the “children’s attendant” position at the Cook County Juvenile Temporary Detention Center. Up in Here, which chronicles the year he spent working at the Audy Home (the detention center’s original and lingering moniker) in the late 1990s, is aware of this mismatch.

In the book, Dostert positions himself as the everyman’s social anthropologist. His allusions to “Chicago’s other side,” and references to Alex Kotlowitz (journalist and author of There Are No Children Here) and William Julius Wilson (famed sociologist of both University of Chicago and Harvard University) do not go unnoticed. But Dostert is the central character in his story, and this ultimately serves to distract the reader. Dostert chalks up his own ineffectiveness as an attendant to the fact that he is white. The kids give him a hard time. He’s an outsider, a “newjack.” But the reader is left wondering: if Dostert’s outsider status disqualifies him from being a good Audy Home attendant, why should it qualify him to write a book on the subject?

Up in Here hits its narrative stride when it shows the interactions between Dostert and the other attendants, or between him and the residents themselves. In an early chapter, an attendant engages Dostert in a discussion on the spiritual origins of racism, encompassing his belief that Eden was found in Africa; Ethiopians are the original Israelites, the people of the Hebrew nation. Dostert listens, transfixed, as the attendant explains, “We’re hated because we’re God’s chosen. See D., the white man took more than our gold and diamonds. He took our identity. We don’t know who we are. If we did, there wouldn’t be so many black kids locked up in this building.”

It’s a compelling passage. Dostert hears Edison out and, in doing so, deepens the character of Attendant Edison. Not just a gruff rule-follower or a renegade rule-breaker (the two molds Dostert uses for his colleagues), Edison has spiritual beliefs and political philosophies. Unfortunately, this early chapter is the book’s high point. The rest of the book devotes too much time to the procedural details of Dostert’s daily “eight hours” at the Audy Home. Too little attention is given to any subject other than Dostert himself.

Dostert tries—through vignette scenes of card games and confinement, medical transfers and recreation hour—to humanize the characters that cross his path. But some combination of his admittedly crushed idealism and his rigidly chronological style of writing prevents that human element from coming through. Up in Here is uncomfortably focused on Dostert’s own humiliation, “Retaining my dignity by not taking shit from children…now seems my only possible mission here.”

Dostert lasts a year on the job before he decides that he was never meant to succeed in the Audy Home—for success would entail molding to Cook County’s masculine ideal of a rule-enforcing, detached, and ever-appropriate attendant. “The Audy Home goads us to such—wishing bad upon kids who have already had more bad happen to them than the rest of us combined. I’m not Mother Teresa after all,” he writes.

More than that, Dostert is no social scientist, no William Julius Wilson. He has little to offer in the way of structural critique. The Cook County Juvenile Temporary Detention Center is the largest of its kind. It is under constant fire for overcrowding, mistreatment of residents, lack of transparency, and general conditions that violate both federal code and basic common sense. Dostert pays some attention to the administrative shuffle and passes judgment on the attendants he sees as “too rough” with the kids. But he comes short of a cogent, critical look at the detention system itself.

Where the book shies away from structural critique, it should make up for it in unlocking characters., to allow the Chicago of “conventions, parades and postcards” to begin to see the Chicago that jails kids, the Chicago that Dostert considers “the other side.”

To be an effective attendant, Dostert doesn’t have to be Mother Teresa. To be an effective armchair sociologist, he doesn’t even have to be William Julius Wilson. But for an effective book, Dostert would need to offer a take on his surroundings that reached beyond his immediate experience, something Up in Here barely achieves.

Mark Dostert, Up in Here: Jailing Kids on Chicago’s Other Side. University of Iowa Press. 254 pages.

I spent a summer in the Audy Home in 1970. I was 14 years old. I’ll never forget my experience. I’ve told very few people. I now work with at-risk teens, for the past 24 years.