On Friday, May 12, the unionized editorial staff of the Chicago Reader unanimously voted to authorize a strike. Their decision was, in some ways, an act of desperation. Twenty-eight months after forming a union, they had not yet reached a contract with the owner, Wrapports, LLC. Last year, in response to a contract proposal calling for better salaries and a retirement plan, the company countered with “no salary increase and a severance package to consist of one day’s pay for every year worked,” according to a blog post by Ben Joravsky, a veteran political writer at the Reader.

Three days later, the Reader’s staff learned that the existence of the paper itself could soon be in jeopardy. Tronc, the parent company of the Chicago Tribune, had announced its bid to acquire Wrapports, which also owns the Sun-Times. In accordance with a request from the Justice Department’s Antitrust Division, the Sun-Times published an ad the next day seeking another buyer. If nobody submits a bid by May 31 tronc can seal the deal.

While Jim Kirk, publisher and editor-in-chief of the Sun-Times—and a former business editor at the Tribune—reassured his staff that tronc would continue running the Sun-Times as an independent entity, the same could not be said about the Reader. In an email to the Reader’s staff a few days later, Kirk said, “It’s a little early to say definitively what will happen with the Chicago Sun-Times or Reader.”

The uncertainty surrounding the Reader’s fate is magnified in the context of its recent circumstances. Since being purchased by Wrapports in 2012, the Reader has experienced layoffs and cuts at all levels of operation, going from forty-seven full-time and part-time staff to thirty-one as of last September. The loss of staff has resulted in loss of content—between 2013 and 2016, the average issue length dropped from seventy-seven pages to forty-six.

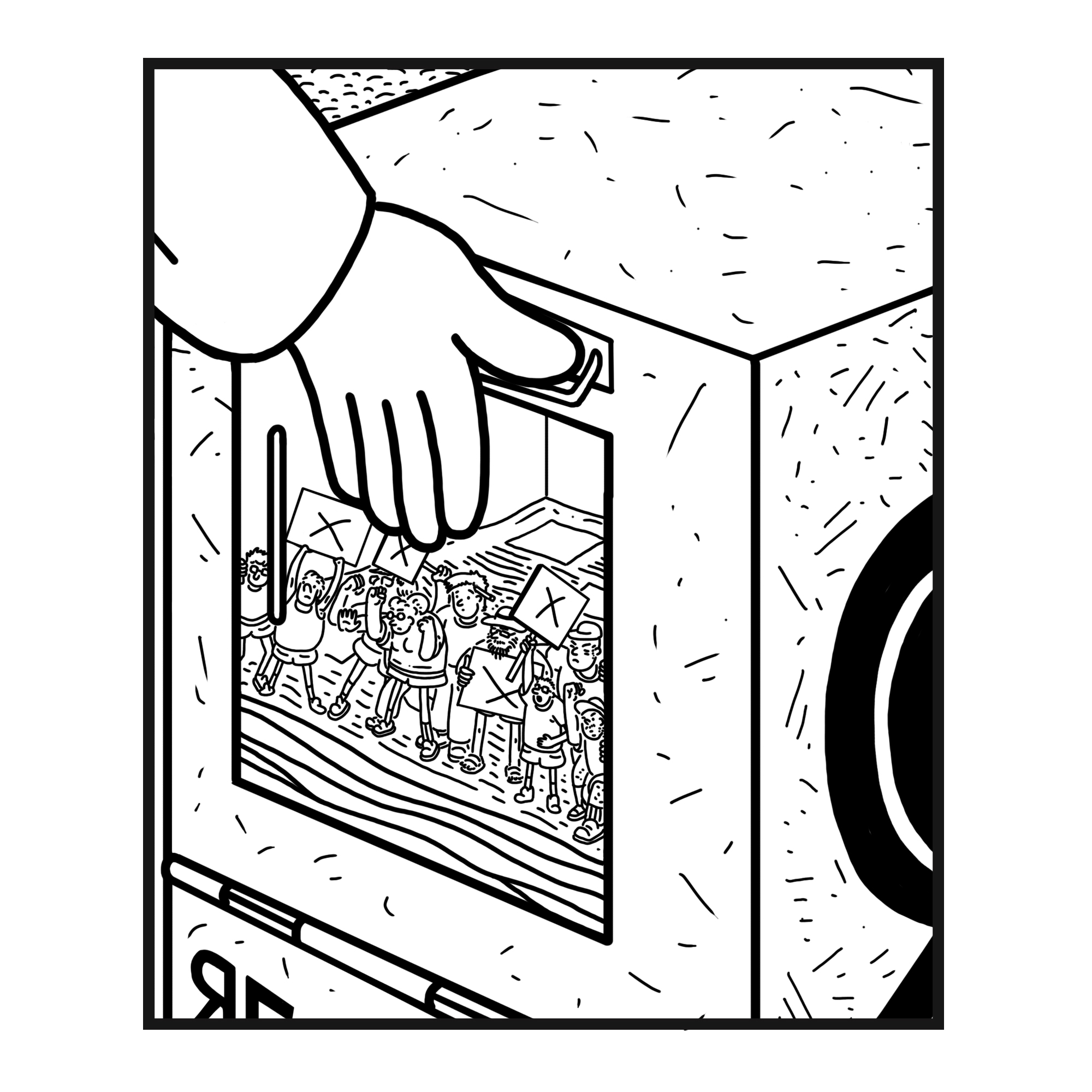

The remaining Reader staff has been scrambling to keep things running. Their reward, in most cases, has been meager pay and little communication from Wrapports. Most staffers have not received a raise in over a decade—not even for cost-of-living adjustments. The day of the vote, some staff members taped printouts of their salaries to an office window to show the extent of the situation. The top salary, at $55,000, was for Joravsky, who’s been a staff writer for the Reader since 1990. Many were below $40,000, even for editors and writers with years or decades of experience.

For 844 straight days, we’ve asked for a fair wage. As you can see—it still hasn’t happened. #SavetheReader pic.twitter.com/kpEoUyTqmD

— SavetheChicagoReader (@SaveTheReader) May 9, 2017

In a 2013 interview with Chicago magazine, Michael Ferro, who was the chairman of Wrapports before dropping his shares and conducting an all-but-hostile takeover of Tribune Publishing in 2016—shortly thereafter naming it tronc—had nothing but vague praise for the Reader: “The Reader is what we wish everything was like. Self-sufficient. They make money. Great morale.”

If that was true in 2013, it is no longer the case. Philip Montoro, the Reader’s longtime music editor, said the pay is so bad that most of the editorial staff work a second part-time job or freelance on the side just to get by—adding an extra ten, twenty, or thirty hours of work to an already full workweek.

Montoro thinks that with the right investments, the Reader can turn things around. Paying employees better and hiring back some of the staff would lead to more content and readers. Ironically, many of the eliminated positions from the past few years have been the ones directly responsible for generating revenue, like advertising executives and marketing directors. If these positions are filled again, maybe the Reader can start subsisting on ad revenue again.

It’s unclear how this will sound to tronc. For one thing, the Reader may need to re-unionize. According to Craig Rosenbaum, the executive director of the Chicago News Guild, if the Reader is handed over in an asset sale instead of a stock purchase, and most of the current employees are rehired, their union will have to be recognized again.

That may be a tough sell at tronc, which seems to view unions with suspicion and where most journalists are not unionized. When tronc gave an up-to-2.5 percent raise to all its journalists last year, it excluded its unionized journalists at the Baltimore Sun, who later lodged a complaint that they were unfairly left out. Even if they do keep their union, there’s no telling how long it will take to agree on a fair contract.

The uncertainty of the Reader’s fate under tronc lies in more than just the contract. If the deal goes through, Ferro, as chairman of tronc, will oversee the publication of several major daily newspapers, including the Tribune and Sun-Times, the Los Angeles Times, the Baltimore Sun, and the San Diego Union-Tribune. Somewhere among these giants, the Reader will have to get his attention.

Much ink has been spilled debating the merits of Ferro’s media empire aspirations. Some think his push toward digital content, monetization of reader data, and flashy projects like the celebrity lifestyle magazine Splash or the Sun Times Network might be able to save print journalism.

Yet many are skeptical of Ferro’s ability to run a media business. The Sun Times Network is a good example. While still at Wrapports, Ferro pushed for its creation, a $14 million investment into a site that would have a presence in seventy U.S. cities and aggregate the most interesting or entertaining stories from each city. But its overworked and underpaid editors and interns were pushed to create as much content as possible, often at the cost of quality. Two years after it was founded, the Network ceased to exist; all the while, the Reader was losing employees left and right.

Montoro says projects like the Sun Times Network are a sign that Wrapports, and by extension Ferro, wasn’t interested in supporting the Reader. The company felt comfortable throwing $14 million at a project that failed quickly, yet only a fraction of that would be needed to give everyone at the Reader a small raise or bring back a few employees. Now that the Reader will be back under Ferro, he might keep the Reader around while continuing to fire employees, or try to change it into some kind of digitized content platform like the Network.

Some of the Reader’s staff, dreading the coming acquisition by tronc, have expressed hope that somebody else will buy the Reader before the fifteen days are up. Maya Dukmasova, a staff writer at the Reader, suggested on Twitter that the Reader be turned into a foundation, like Harper’s Magazine. In 1980, Harper’s was in a tough spot—some estimates had the paper losing $2 million a year—when the MacArthur Foundation stepped in, bought it out, and made it a nonprofit. It is now able to cover its costs through ad revenue and subscriptions.

The odds are stacked against this kind of buyout. As the Reader has had to rely more on the Sun-Times for certain functions over the years, the Sun-Times in turn has become more synchronized with the Tribune. In 2014, Wrapports sold the Sun-Times’ suburban outlets to Tribune Publishing, and the Tribune took over circulation of the Sun-Times in 2007 and printing in 2011. With so many facets of running the Reader already closely integrated with tronc, anybody else interested in buying the paper is at a significant disadvantage.

For now the Reader will have to wait and see. But in some ways, the fight for better pay and more investment goes beyond the Reader. For Joravsky, it was about the future of journalism.

“I’m the old guy in the room,” he said. “The young kids think the world is just the way it is,” but things used to be much better for journalists. Many of the Reader staff are still young. “What about when you want to buy a house? Have kids?” he asks. “You’re not going to stick around in journalism the way it’s going.”

The case for serious journalism is that it holds the most powerful people accountable, whether through persistent questioning or comprehensive investigation. But Joravsky thinks the value of the Reader lies also in its specific place among Chicago’s media institutions as a voice of dissent. He remembers when bringing the Olympics to Chicago was on the table and almost everyone in the city was on board. But the Reader went against the grain. Throughout its history, the Reader has also reported tough, politically unpopular stories on segregation, police torture, and school funding; ran one of the first profiles of Barack Obama in 1995; and has been known for its meticulously-edited features on everything from World War II to Chicago’s infamous “lipstick killer” of the 1940s to a tiny radio station run by Christian fundamentalists near the Wisconsin border.

The Reader occupies a unique role in Chicago’s media landscape that often allows its stories to have the kind of impact generally associated with larger, better-funded organizations. A recent Reader investigation into the abusive practices at Profiles Theatre led to its closure a few days later. “Journalists dream of having that kind of effect,” Montoro said.

Saving the Chicago Reader will undoubtedly be costly, and may even mean that funders will have to operate at a loss. The cost to the city and its culture if it folded, however, would be far greater.

Did you like this article? Support local journalism by donating to South Side Weekly today.

I worked for The Sun-Times doing IT during and after the buyout. They fired around 600 people when they merged offices. After it was all starting to settle, I was fired. I saw first hand how unfair the Reader staff was treated, and there was nothing I could do. Just like the quotes above, money was thrown at things that didn’t work. I can only imagine how bad things are today.