On August 8, as the Republican National Committee concluded its three-day summer meeting in Chicago, Paul Ryan sounded the new message of the Republican Party. “We have to go to corners of the country that are not used to seeing us,” he told his fellow party leaders.

But with less than three months until the November elections, Ryan and the Republicans were surely hoping that people had begun to get used to seeing them already. The plans for their change of strategy had been laid much earlier.

In December 2012, after a historic election season in which, for the second time, African American voters turned out at a higher rate than white voters, RNC Chairman Reince Priebus commissioned the “Growth and Opportunity Project.” Intended to “grow the party and improve Republican campaigns,” the report found that public perception of the party was at “record lows,” that Republicans were seen as “scary,” “narrow-minded,” and “out of touch,” and that things would only get worse, when, “in 2050, whites will be 47 percent of the country” (they were sixty-three percent of the population at the time of the report).

The report determined that Republicans desperately had to find new voters among minority communities. “This priority needs to be a continual effort that affects every facet of our Party’s activities,” it said.

Last October, a memo went out from the RNC’s director of communications, updating the party on the “new approach.” Whereas, in the past, Republicans had spent most of their time hording cash to use in last-minute, pre-election, three-month binge-sessions, the new plan would be to establish a permanent ground game. “This work isn’t about one campaign or one election year.”

Finally, on May 7 of this year, the RNC formally announced Victory 365, “a new permanent grassroots field operation,” focused heavily on engagement with minority communities, that would be “unlike anything the RNC has done in past election cycles.” It was the official theme of the Chicago meeting in August.

On the last day of September, Jim Oberweis, the Republican candidate for U.S. Senate in Illinois, opened a campaign office at 6607 S. King Drive. He stood in a room with bare white walls and polished wood floors, flanked by several African-American community leaders, in what used to be a soul food restaurant.

Though the election was just a month away, with early voting to begin on October 20, Oberweis’s message was humble and nonspecific. “I don’t have the answer to every problem,” he admitted. “I’m pretty knowledgeable about the economy. I’m less knowledgeable about how to solve the gun violence. But I will listen.”

The community leaders who spoke were more assertive. “The reason we put this office here,” Pastor Corey Brooks announced, “is because we want to send a message, to the African-American community and to Dick Durbin, to let him know we are not a novelty.” At that, there was a decisive round of applause. “We don’t stand alone.”

Over the past year, a number of South and West Side pastors, either independents or former Democrats, have publicly endorsed Republicans. Brooks, of New Beginnings Church, just across the street from the Oberweis campaign office, is one of them. Pastor Ira Acree, of Greater St. John Bible Church in Austin, who was also in attendance at the opening of the Oberweis office, is another. Still others include Pastor James Meeks, a Democratic state senator until he retired last year, Marshall Hatch, who has served as Rainbow PUSH’s national director of religious affairs, and Bishop Larry Trotter, who has been active in civil rights causes and wants a south suburban trauma center.

They are too few to be called a movement, and too individually distinct to be called a collective. Brooks has endorsed both Oberweis and Bruce Rauner, the Republican candidate for governor. Meeks, Hatch, and Thurston have endorsed Rauner but have not said anything publicly about the Senate race. Trotter has endorsed Oberweis but hasn’t said anything about Rauner. Acree will vote for Oberweis but also Democratic Governor Pat Quinn (though Brooks, in one media appearance, included him in a list of pastors supporting Rauner).

What they have in common is their dissatisfaction with the say African Americans have, or don’t have, in state politics. They think that Democrats have taken the African-American vote for granted, and that African Americans have been disenfranchised as an assumed constituency: not every politician has to listen to them, and those that do don’t have to listen very hard. The pastors who have endorsed Oberweis cite a “lack of access” to Durbin (Trotter), a failure to address “the critical needs of our community” (Acree), and not enough “concern about African Americans” (Brooks). All three voted for Durbin when he was last up for reelection, in 2008.

“I’m not a new Republican, that’s not the message I wanted to give,” Acree told me.

“I look around and see so many people struggling, getting gunned down, because people are desperate and resorting to these desperate measures, because of the economy, they can’t get jobs,” he said. “And when I see politicians playing games it frustrates the living hell out of me.”

“Does all this mean we should support Republicans whose policies are against the interests of our communities?” Hatch asked in an editorial he wrote for the Austin Weekly News, in which he endorsed Rauner. “Of course not. But all this does mean that we will have to learn how to play two-party politics in order to win in every election.” Hatch called the relationship of African-Americans and Democrats “dysfunctional,” and said that Quinn only had to appoint an African-American as his running mate to have gained more credibility.

“If [Rauner] pulls this off with African-American support, there’s going to be a different relationship with African-Americans and the Democratic Party,” Hatch told CBS in September.

Both Oberweis and Rauner have made headlines for their efforts to court the African-American vote: Oberweis for the office at 66th and King, and Rauner for putting $1 million of his own money in the South Side Community Federal Credit Union over the summer. (The credit union’s president, Gregg Brown, had never met Rauner prior to the deposit and has not endorsed him.) And they have been especially vocal about the pastors’ endorsements, appropriating their rhetoric of dissatisfaction. “I think he’s never listened to the needs of these communities,” Oberweis told me, referring to Durbin and the South Side.

In the second gubernatorial debate, held at the DuSable Museum in Hyde Park and dedicated to African-American issues, Rauner proudly stumbled through the names of his endorsers: “I’ve been very honored in this election to be endorsed and supported by many prominent African-American leaders here. Rev. James Meeks, Rev. Corey Brooks, (um) Rev. (uh) Marshall Hatch, (uh) Commissioner Lou Laford, (uh) Dr. Willie Wilson, Dr. (uh), Rev. Thurston, many others, dozens of others.”

Though the pastors, like Brooks and Acree, have been vocal about their decisions, they’ve also been careful to frame them as a matter of personal choice, a sign that African-Americans are not beholden to any particular party or candidate. They have put their faith in the individual candidates’ abilities to create jobs, but they have not done the same for all Republicans, and they remain cynical of both parties. Ultimately, they reserve their right to cynicism, and they are most concerned with shaking up the current system and empowering African-Americans.

In April 2013, Pastor Ira Acree went to Springfield to lobby for sensible gun control legislation, along with Pastor Marshall Hatch and other members of the Chicago Clergy Coalition, an interfaith group. There, the coalition delivered petitions containing 50,000 signatures for “common sense gun legislation,” calling for criminal background checks on all gun purchases, registering all guns, reporting all stolen guns, and an outright ban on assault weapons. “Something radical needs to be done to stop the unchecked flow of guns,” Acree said at the time.

The experience destroyed what confidence he had in state politics. “They made all these speeches, ‘We’re for background checks, banning assault rifles,’ all that,” he recalled, “and then they can’t pass the legislation. That does not pass the smell test.”

At the time, Democrats controlled, and still do, the House, the Senate, and the Governor’s office. “These people are in control and they don’t do anything,” Acree said. “When we stood out in the cold, collecting signatures, and the Democrats couldn’t find the courage—who cares about speeches about gun legislation if you’re not going to implement the laws?”

Jim Oberweis has an endorsement and an eighty-three percent favorability rating from the NRA, thinks that gun control does not reduce gun violence, and says on his campaign website that gun laws only make those who think otherwise—people like Acree, who endorsed him— “feel good.”

But it would be tough to call Acree’s endorsement of Oberweis naive, or even a compromise. “In the last election cycle,” he told me, “I would have chopped Oberweis up like chopped liver. I would have said, ‘If you’re not for gun control, I’m not for you.’ ”

To the Democrats and Republicans who play “political games,” Acree has responded with his own political long game. “It’s about making a statement,” he emphasized. It’s not about this election cycle so much as bringing African-Americans “back in the conversation in the two-party system.” It’s about turning to African-Americans for policy rather than turnout, about making African-Americans a true constituency where they currently are not. “If we push back and show that we could possibly vote for the Republican Party one cycle,” he says, “maybe we could get some respect.”

Acree’s position has come under fire, from both within the community and without. In an editorial in the Austin Weekly News, Dwayne Truss, a public education activist, also from Austin, argued that Acree had “leveraged for a lot less than what the Democratic Party has actually done for the black community.” Still, Acree’s position is deliberate and takes this criticism into account.

He cites Oberweis’s record on jobs and “vision for economic growth” as affirmative reasons for his endorsement, and hopes that Oberweis could help solve “the number one issue in my community right now,” which is the economy. He voted for Jim Edgar, the Republican governor, in the 1990s. But he was still a Democrat then, and he doesn’t see himself as suddenly becoming conservative now.

“I’m a Democrat, and I’ve been a Democrat since the first time I voted for [Harold] Washington in 1983. I’ve been a Democrat my whole life, but when I see the mean-spirited, blatant disrespect that this party dares to give black men who think independently, it really leaves a bitter taste in my mouth.”

But, “I’m not going to shut up, I’m going to continue to try and speak truth to power, and elevate our people, because they’re getting screwed.”

The winter before Acree and the Chicago Clergy Coalition faced the Chicago cold to collect signatures, Pastor Corey Brooks spent ninety-four days atop the roof of a motel. He wanted to use the attention to raise the money needed to buy the motel, and later, to build a community center on the site, across the street from his church. Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton came to visit him. He told the New York Times that, while he would never run for office, he would “always fight against the social ills of our society.”

The motel has since been purchased and torn down. The now-deserted lot runs right up against the small building at 6607 S. King, the one with the Oberweis campaign office, which Brooks’s church also owns. After the election, Brooks plans to tear it down as well, to make more room for his community center.

Before endorsing Oberweis, in May, Brooks had never voted for anyone running against Durbin. (In 2010, he also voted for Pat Quinn.) Since May, he has led Oberweis on trips around the South Side, including five visits this summer to the corner of 79th and Cottage Grove, as part of Brooks’s anti-violence “Brothers on the Block Program.” (“I have been amazed by how friendly the people are in that neighborhood,” Oberweis told the Sun-Times.) Both say that Oberweis has contributed just a one-time $1,000 donation to his community center program, Project HOOD (“Helping Others Obtain Destiny”).

Like the other pastors, Brooks came around to the idea of endorsing Republicans because he thought the Democrats were taking the African-American vote for granted, at the expense of neighborhoods like Woodlawn. “When you look at the landscape of our community, everything seems to be in disarray. Our schools are the worst, our unemployment is the highest, and our crime is ridiculous,” he says. “All of this has taken place under what he calls a “Democratic system.”

“So for the people who’ve been so loyal to [the Democrats], to have all these issues in their communities, speaks volumes for how they’re taking advantage of our vote. Because if these were problems in other voting areas that belonged to other constituencies you can believe they would have done something about it.”

He now considers himself an independent.

“I’m gonna support the best candidate I feel for the position. Sometimes that’s gonna be a Democrat, sometimes that’s gonna be a Republican. But I’m no longer going to be voting for a person just because they belong to a certain party. That is never going to happen again. Ever.”

It’s difficult to pin down Brooks politically. He defends his endorsements on the grounds of jobs and school choice (“When you limit me to go to an impoverished school that’s already underperforming and underfunded, that’s racism, that’s exploitation”). He’s in favor of raising the minimum wage nationally and wants an elected school board. He doesn’t trust corporations any more than the government, but he doesn’t really trust either (“I think we have to keep everyone accountable”). He says he would not have voted for Karen Lewis or Toni Preckwinkle for mayor—claiming that neither had a chance to win, despite their overwhelming leads in pre-election polls—but that, “as it relates to the African-American community, [Emanuel] has done a very poor job.”

“My point is, insanity is this: doing the same thing over and over, trying to get a different result,” he explains. “It is very insane for us, as a people, to keep going to the same well and it’s poison. We need to change wells. See what another well has to offer. We need to change systems, see what another system has to offer. You can’t keep going down the same road knowing what the end is going to be—a train.”

The pastor’s endorsements are a response to that disillusionment before they are an embrace of Jim Oberweis and Bruce Rauner. “For me, this is about job creation and the economy. That trumps everything for me, Brooks says. “I mean everything. Because if African Americans don’t have jobs in these neighborhoods, there’s going to continue to be a lot of violence. And so, one of the things that has to happen is we have to get more jobs, the economy has to get better.”

“So the fact that both [Rauner and Oberweis] are businessmen to me is a big, big deal.”

Brooks has received death threats for taking his position. Last Friday, he received five phone calls, from an unknown source, in a harshly disguised male voice. In the one call Brooks made publicly available, he is called a “sell-out,” an “Uncle Tom,” and “a puppet for Bruce Rauner.” On Saturday, Brooks reported that $8,000 had been stolen from a donation box in his church—money that was intended for the community center.

The next day Brooks delivered a powerful sermon in which he alluded to, but did not mention, what he had been trying to achieve with his endorsements. “People will try to label you, and when they label you they limit you,” he told the crowd that had come out in his support. He noted that the majority of the prison population in Illinois is black and that fewer than half of black adults old enough to work in Illinois were employed. “If you want to do anything in this world you cannot bow down to everything people tell you to bow down to.”

Though he invited Rauner to say what he usually has to say—”I’m here to go to work for you”—after the service, Brooks reiterated to the media what he’d told me before, that he did not want to ever be a member of either party.

Two Saturdays ago, on the weekend before the start of early voting, I paid another visit to the Oberweis office at 66th and King and happened to find Jim Oberweis.

A single room, deep but not very wide, the office has the look of a just-constructed suburban home—one that someone filled with posters of Chicago wards and political yard signs at the last minute. There are a few desks and chairs in the back, which is where Oberweis, Brooks, and a few others were sitting. Though Brooks and the political consultant who runs the office, James Jones, had been taking Oberweis around the South Side on a day-long campaign tour, one of their appointed stops had fallen through, and Oberweis was waiting for them to figure out the next move.

At the time, Oberweis was more than two-digits behind Durbin in the polls (he still is), and spending more time campaigning on the South Side than one might expect this close to the election. Unlike Rauner, he didn’t even have the votes down among his base, and those aren’t on the South Side.

Oberweis said he first met Brooks back in 2012, at a fundraiser for Project Hood. He said he’d been introduced to Brooks by Joe Walsh, the former Tea Party congressman from the Chicago suburbs. In terms of policies that would benefit the South Side, Oberweis says he would create jobs, simplify “the so-called crony capitalism that has become a major part of our tax code,” and promote school choice.

Already, he said, “We’ve been providing a list of jobs available to Pastor Brooks, so he can pass it on to people looking for jobs. I just sent him an email list within the last week of several jobs that are available. And on top of that we are working with Pastor Brooks to make an Oberweis Dairy franchise available to Project HOOD as a way for people to learn basic skills, and possibly make a training center here on the South Side.”

Oberweis has said on the campaign trail that “we as Republicans probably have the greatest outreach effort [on the South Side] that we’ve ever had,” and that “this is a new relationship with the African-American community.” But most of his engagement with the South Side seems to go through Brooks, and he invokes him repeatedly. Brooks has risked his reputation with his endorsement but has drawn increased attention to his already popular programs such as Brothers on the Block and Project HOOD. Oberweis has gotten good publicity but few to no immediate practical benefits in return.

Meanwhile, Oberweis, who has only raised a few hundred thousand dollars in non-personal contributions to his campaign, is expected to pay Jones $150,000 total as his coordinator for African-American outreach, according to Jones. (He said he’d been paid $40,000 thus far, which is borne out by campaign filings.) Jones is leasing the office from Brooks at a rate of $500 a month.

Until this year, Jones had mostly consulted for Democrats. He said he had worked for Durbin before, and campaign records show that, as late as 2011 and 2012, he had been paid by Democrats Napoleon Harris, Bernard L. Stone, and Bob Fioretti, the progressive challenger to Rahm Emanuel for mayor.

Oberweis “has hired a lot of African-Americans for his campaign,” Jones said. “I have a crew of guys that I work with year-round, and I try to keep them employed. Off-season, we’re doing real-estate, cleaning out houses, and election season comes around, they look forward to that money. They told us they weren’t going to put the money in the street because they already got the vote, they already got the African-American vote. And I thought that was an insult. Like, what the hell are you saying that you got the African-American vote already that you’re not going to put—man you’re crazy. So we changed and went with Oberweis, because he offered us a contract, you know.”

Ron Holmes, a spokesman for Senator Durbin and himself an African-American from the South Side, stressed that a brick-and-mortar office “matters a lot less to people than what you do when you’re elected.”

“We’re not taking anything for granted,” he said.

Republicans have been mum about the details of their attempts at minority engagement. They have more visibly reached out to African-Americans in swing states like Michigan, North Carolina, and Georgia in this election cycle. But they are building roots across the country. On November 7 of last year, just over a week after the GOP memo, the Illinois Republican Party announced the hiring of a new state director, Anthony Esposito, who, “under the RNC’s new model,” would “implement a person-to-person grassroots organizing program.”

“Tony’s expertise and experience will be invaluable as we work toward victories in 2014 and beyond,” Jack Dorgan, the state party chairman, was quoted as saying. “Democrats have taken Illinois voters for granted.”

Andrew Welhouse, the communications director for the Illinois GOP, said he couldn’t provide any details about the Republicans’ new ground game, but added that “the Illinois Republican Party and the RNC are working closely with the campaigns,” and that they were active on the South Side of Chicago.

Earlier in September, the Republican Party quietly opened three offices of its own on the South and West Sides: one in Chatham, and one in Ashburn, and one in Austin (Acree and Hatch’s neighborhood). By coincidence or not, the Chatham office—at 511 E. 79th Street—is just a few blocks west of the corner where Oberweis has repeatedly campaigned, at 79th and Cottage Grove. In a DNAinfo article about the opening of the Chatham office, published September 5, Oberweis was quoted sounding the familiar refrain. “The Democrats have taken people for granted for many years,” he said.

The author of the DNAinfo article wondered “whether this was some kind of brilliant political strategy or an act of desperation.” It is a mix of both. These offices are some of the early underpinnings of the GOP’s national new direction—a direction it needs to take.

Chris Cleveland, the vice chairman of the Chicago Republican Party, told me that “some” of the three South and West offices will be permanent, or at least long-term, outposts—although plans will depend on the outcome of the election. He confirmed that they were part of the national effort of inclusivity and engagement that began “after 2012,” when “the RNC stepped back and tried to figure out what went wrong.” Cleveland stressed that bringing minorities into the party and speaking to urban concerns were high priorities, affecting “every level the party is involved in.”

“We’re obviously ground zero for the effort to reach out to urban areas and minorities,” he said.

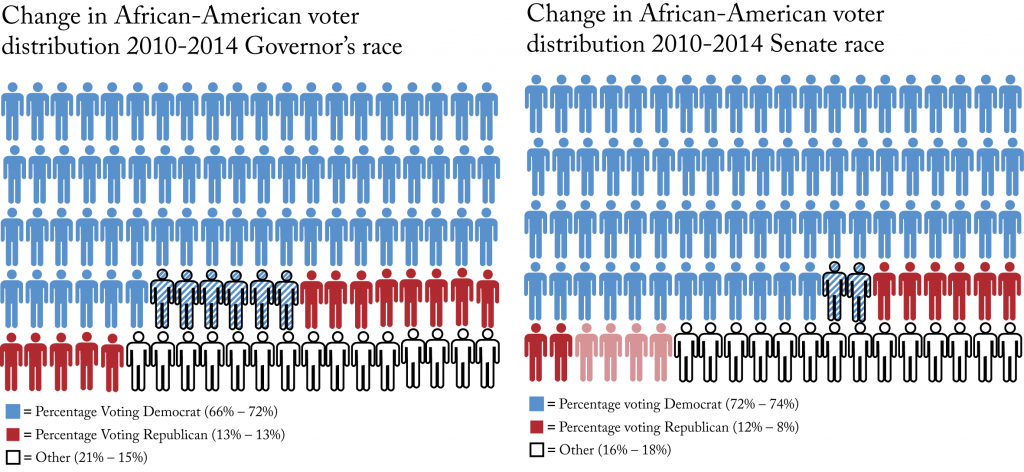

But despite their efforts, neither Oberweis nor Rauner has had much success in courting the African-American vote so far. A Tribune poll in early September found that African-Americans were supporting Durbin by more than a ten-to-one ratio. Another Tribune poll, published October 23, found that only three-percent of African-Americans were supporting Rauner. Other polls have also found him in the single digits, the highest at ten, which would actually put him behind the 2010 Republican candidate, Bill Brady, who polled at thirteen-percent among African Americans in the final poll before he lost.

This doesn’t mean Republicans can’t or won’t find more African-American voters in the future. A poll conducted by the Wall Street Journal and NBC this summer found that, while likely voters who are black prefer a Congress led by Democrats by seventy-seven percent to ten, more blacks consider themselves “conservative” than “liberal”: thirty-seven percent to thirty-three.

But the partnerships Republicans have formed in this election cycle don’t yet look like lasting ones. At the most, they have won over some voters with conservative tendencies. At worst, they have been bested by community leaders who want their politicians to answer to them and adapt more aggressive and reform-minded policies, and who are getting more out of the relationship than the Republicans are. Either way, it’s tough to sell a message of individual opportunity to people committed to fighting continued discrimination and segregated neighborhoods.

The African-American leaders Republicans are pursuing on the South and West Sides feel left out of a party that has only begun to call for a $10 minimum wage ($10.10 if you’re Dick Durbin) because its white base of people who already make more than that has begun to embrace it as part of a vaguely progressive self-identity. That doesn’t mean they’re about to start joining the party of voter ID laws and trickle-down economics in large numbers. In Chicago 34.1 percent of African Americans live below the poverty line. Personal relationships are a start, but the Republicans will need more than that—as will the Democrats.

“I love Bruce, I really do,” Brooks joked on Sunday, after the sermon, “but I don’t love you that much.”