Halfway Home: Race, Crime, and the Afterlife of Mass Incarceration is a book about life on parole, and the wringing circumstances that the incarcerated are sentenced to even after their release. We are often barraged with platitudes about freedom and the pursuit of opportunity—rights bestowed upon us via citizenship in a country which, since its founding, has not been an equitable site for either. We are similarly told that every American deserves an equal chance at reaching their fullest human potential and that the job of policymakers is to ensure that the nation is moving toward that ideal every day. But there are caveats to that ideal. Obvious ones are made evident when you step foot in an underfunded school, or as the Red Line clambers south to the 95th/Dan Ryan Terminal Station (though city limits extend to 138th Street). Less obvious caveats however, intentionally hidden from the public, are the lives of the incarcerated—people who, whether guilty or innocent, will never live the same lives again.

Halfway Home speaks not of the consequences of crime—for many inmates may not have committed a crime at all—but the consequences of simply having a criminal record, something that you can be stamped with at the whim of a bitter judge, a disinterested public defender, or a police officer having a bad day. It establishes poverty, crime, and incarceration as forces that are made hereditary by U.S. policy. Furthermore, it personifies these forces as an affliction, one that locks doors, burns bridges, separates families, and swallows the identity of an individual, overwhelming their life thereafter while working to reduce their life chances to ash over time.

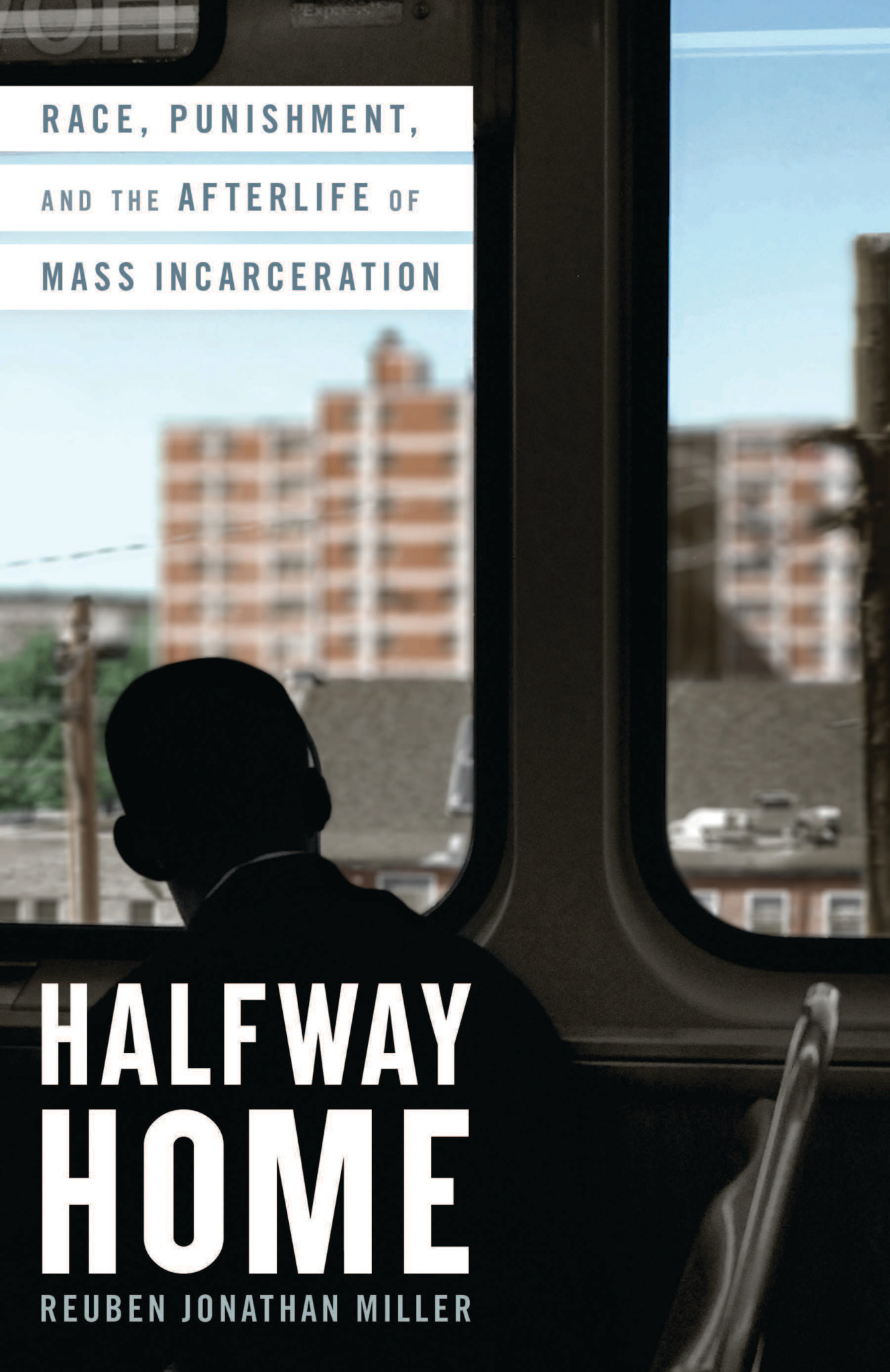

The book is written by Dr. Reuben Jonathan Miller, an assistant professor of social work at the University of Chicago, who has not only studied the lives of those damaged by the carceral system for nearly twenty-five years, but has been proximate to the system his entire life due to the incarceration of his father and two of his brothers. What Miller calls narrative nonfiction makes for a work of both rigorous scholarship and deeply human stories that reveal the nuanced impacts of a domineering carceral system. He does this by telling the stories of various people who were formerly incarcerated, how they came to be in their situation, and how they’ve struggled with the stamp of incarceration the moment they stepped beyond the gates. What he found in these individuals were common trends: a mother or father who was incarcerated, a victim of abuse in their youth, institutional violence, poverty, skin color. He describes their circumstances as that of a new form of citizenship, carceral citizenship, because as long as their lives are marked by their criminal record and the law permits discrimination on that basis, they will never have the same inalienable rights as normal citizens—there will never be a place for them.

We meet Yvette from Ypsilanti, who’d been out of jail for over a decade, serving in the prison ministry with the church she joined after her release. Her job was to provide hope to those who had not yet reached the end of their sentence (and to those who never would). She is a gifted and beloved singer who Miller says has a magnetic personality. She is also a hard worker, picking up a job at the Office of Public Health and Welfare as an administrative assistant. She didn’t check the box where the application asked if she’d been convicted of a crime, and in the 1990s there was no robust screening technology that’d connect the dots. Besides, the past was behind her; she had a family now, she was sober, and she hadn’t been arrested in over a decade. But when an injury sidelined her from work and she filed for unemployment to hold her over until her return, gossip from the public aid office made its way back to the Health Department and she was let go. A shallow analysis would ask if the circumstances would’ve been different had she told the truth on her initial application, but the reason she was let go was not just because of her record, it was because an employer like the Health Department could be sued for having a felon on the payroll. The box wouldn’t have mattered because her employment was prohibited by law.

Miller deploys a number of metaphors to help the reader grasp the struggle of incarceration’s afterlife. Especially poetic was his reference to Nina Simone’s rendition of “Sinnerman,” a song about a sinner seeking to hide from his own judgment. The sinner runs to a rock, a river, and a sea for refuge, but is rejected at every checkpoint. Miller likens this rejection to the rejection that those with criminal records face throughout their lifetime—from not being able to rent an apartment, to being rejected from jobs with the lowest barriers to entry, to being rejected by companions whose love could not outlast the length of their sentence. “Just as sin puts a barrier between people and their God, a criminal record separates people accused of a crime from the life-giving institutions of a free society,” he says. The way Miller catalogs the rules and restrictions set by parole officers throughout the book makes it clear to the reader that parolees are not meant to be free at all. In fact, any violation of the already stringent rules could immediately land a parolee back in prison. There is hardly anywhere for them to turn.

When Miller caught up with Jimmy, who was recently out on parole, Jimmy was optimistic. He recently got a new cell phone, and was excited to have job postings sent directly to his phone via email. Jimmy’s plan was to get his resumé together and go to the workforce development agency that his parole officer directed him to. On the day that Miller accompanied him, the parole officer sent Jimmy to a workforce agency that was no longer operating. Not only that, but Jimmy had run out of bus fare, something he could’ve replenished at the agency if it were open. Now Jimmy would have to walk nine miles to get to the next agency on the resource list, he’d then have to walk to his court-ordered AA meeting, then he’d have to walk all the way back to the parole office for his weekly check-in. If he missed any of these appointments he could be sent back to prison. Nearly a quarter of all prison admissions in the previous year were for similar parole violations, a lot of which could’ve merely been the result of bad luck. The slightest mistake by a parolee can land them back behind bars, so it’s fortunate that Miller was there to give Jimmy a ride, one of the many favors that carceral citizens depend on in times where everyday mishaps could cost them their freedom.

The system is broken in many ways. Miller powerfully ties several eras of history, law, and US policy into the stories of his companions. He tells the story of Brown v. Mississippi, the Supreme Court case in which coercing a confession was made illegal. This case paved the way for the plea deal, which Miller suggests is just another form of coercion. He tells the story of how the rise of mass incarceration coincided with the decline of Detroit’s Black middle class, creating a pipeline fed by poverty and its externalities. He ties in policies as recent as the Second Chance Act of 2007, which President George W. Bush signed into law. The legislation provided $165 million to community-based services for formerly incarcerated people, like halfway houses and reentry programs, and it was the largest ever piece of legislation dedicated to that population. But the success of reentry programs has its extent.

“Reentry programs don’t seek to remove the barriers formerly incarcerated people face. They can’t,” he says. “In Chicago, there are over seven hundred policies that keep people with criminal records unemployed. More than fifty bar them from housing.” Inmates are still locked out of society despite federal resources being poured into their supposed reassimilation. When Miller spoke to the director of the city’s reentry and workforce-development programs, he pressed on the topic of how they measure success. “We look for certificates of completion,” the director says. But certificates only provide evidence that a person has gone through programming, they do not ensure that the former inmate has secured a job, stable housing, or upward mobility. Certificates don’t do anything to change the laws that make it easier to land back in jail than to build a life, and this is what Halfway Home asks us to understand.

While there are no policy recommendations at the conclusion of the book, Miller exposes the unforgiving nature of living with a criminal record in a way that begs for change. He speaks on their predicament plainly, saying, “There is no place for them to go because no place has been made for them, not even in the public’s imagination.” As Halfway Home illustrates so well, American society is built to create the origins and the afterlife of mass incarceration, confining poor, mostly Black people to a particular fate. American phenomena that still haven’t been dealt with, like state-sponsored disinvestment, over-policing, racial discrimination, and legal malpractice, all work together to keep communities oppressed and prone to convictions—the stamp of a criminal record works just as effectively. Through heart-wrenching accounts and vivid prose, Halfway Home accomplishes its goal of putting the reader in the shoes of the incarcerated, challenging us to understand that every prison sentence, in more ways than we think, is a life sentence.

Reuben Jonathan Miller, Halfway Home: Race, Crime, and the Afterlife of Mass Incarceration, Little, Brown, and Company, 352 pages.

Malik Jackson is a South Shore resident and recent graduate from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where he majored in Urban Studies. He last wrote about renters struggling amidst a housing crisis during COVID-19 for the Weekly.

This is a very good story and every one should read it. Everyone need to know this. God bless you and keep on writing.