The word “Chiraq” is multilayered, evoking many images. A direct comparison to the ongoing conflict in the Middle East often found embroidered on T-shirts, the term is both a badge of honor and a rationalization for the normalization of Chicago’s conflicts. The word “Chiraq” prevents others from seeing the artistic, musical, and cultural movements that were birthed in the city, and instead leads them to focus on reports of violence. The word has made its rounds through the media, even lending its name to Spike Lee’s 2015 movie, shot on the South Side and poorly received in the city. We assign monikers to places and objects we admire, but also use them as a means to categorize difficult concepts. “Chiraq” draws in curious spectators, then distances them by moving the city an ocean away.

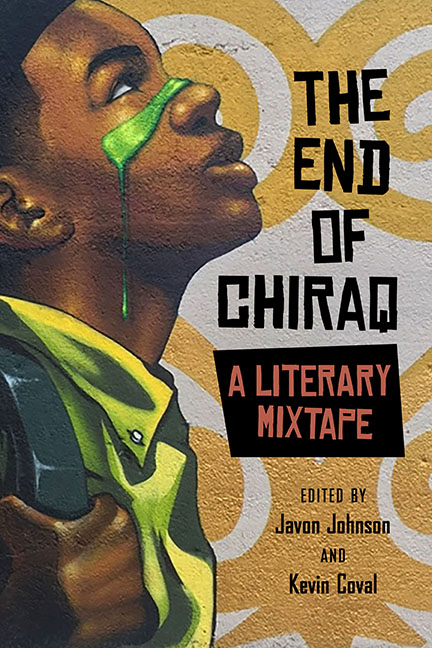

In The End of Chiraq: A Literary Mixtape, a new anthology edited by Kevin Coval, local literary celebrity and Young Chicago Authors artistic director, and Javon Johnson, director of African American and African Diaspora Studies at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, each section of the book works to dispel the often-shared narrative that Chicago is a battleground. The first section, “Welcome to Chiraq,” takes an intellectual approach to the nickname and the violence in Chicago.

Each author offers insight into how the nickname influences other’s perceptions of the city. Well-known organizer Mariame Kaba, in her piece entitled “To Live and Die in ‘Chiraq,’ ” sums this up well: “ ‘Chiraq’ is a war zone that invites outsiders to offer their prescriptions for how to ‘solve’ the problem of violence. In ‘Chiraq,’ community voices are drowned out.” The perspective non-Chicagoans are privy to, one driven by news reports of shootings, leaves out the opinions of Chicago’s residents.

This sentiment is shared in other pieces of the first section, like in St. Louis writer Jacqui Germain’s poem “How America Loves Chicago’s Ghosts More Than the People Still Living in the City: An Erasure Poem.” Borrowing lyrics from from Chance the Rapper’s “Paranoia,” the poem highlights society’s fascination with violence in Chicago. In the line “Eyes been on the gun, on the dying, the shit neighborhood” Germain highlights not just that fascination, but also the lack of interest or “eyes” on the positive aspects of Chicago.

However, reaping the benefits of Chicago’s cultural landscape, while turning a blind eye to the other issues, is possible if you are affluent enough. This is explored in the second section of the book. “A Tale of Two + Many Cities” addresses Chicago’s segregation and how government institutions contribute to the discrepancies between impoverished people of color and white people. Johnson writes in the introduction that the section is meant to show how the state is “a participatory agent in the city’s violence.” As different areas of Chicago begin and continue to gentrify, those that benefit from the gentrification are members of the same group that can afford to ignore Chicago’s segregation.

“FAKE” by poet Toaster. paints a picture of the imagined conversations between newly-minted Chicagoans: “no no no I live in the good parts of Chicago/which means/the safe parts/which means/the north side/which means/away from brown people.” There are many parts of Chicago that people don’t see. Works in this section of the book highlight how residents navigate or ignore the city’s deep segregation. As Melinda Hernandez writes in her poem “Into a White Neighborhood,” “White neighborhood don’t know/mega mall is an art gallery./White neighborhood see/mega mall as an urban outfitters.”

“Contesting the Narrative,” the third section of the book, flows naturally—like a musical mixtape—from the themes in “A Tale of Two + Many Cities,” challenging outside perceptions of the cities by highlighting its art and culture through lyricism and free-form pieces. “we real. we/steel we./still here./we no fear,” writes Kevin Coval in his poem “we real.” In an essay, tara c. mahadevan touches on Noisey’s portrayal of Chicago, calling their 2014 documentary series on the city’s drill scene “a disrespectful, misleading, and muddied viewpoint of a city rich in culture.” Nile Lasana, in “windowpain,” makes a plea of understanding: “I just want to speak for the soul/Tell the truth about the ‘warzone’/I call home.

We explore Lasana’s truth the final sections of the book. In sections “The Culture is the Art” and “The Future of Chicago,” this literary mixtape highlights the bright notes of Chicago. “Who needs an X-Box/hoverboard/basketball rim/when you have the stoop,” asks Jalen Kobayashi in “The Stoop.” comparing front-step stages to podiums and other platforms for sharing. The writers go on to highlight the fruits of Chicago’s artists and activists. Leah Love interviews three Chicago creatives on Afrofuturism, an aesthetic that has roots in the city, and Yana Kunichoff (a contributor to the Weekly) and Sarah Macaraeg highlight the beginnings of reparation legislation in Chicago—a victory for local activism—in their report “How to Win Reparations.”

This book offers a perspective that non-Chicagoans can’t get from news coverage, insults from Trump, or a short visit. As Sammy Ortega writes in their poem “Water Pressure”: “Never mention/the day where/Most of us are safe/from fire.”

Kevin Coval and Javon Johnson, The End of Chiraq: A Literary Mixtape. $20. Northwestern University Press. 192 pages

Sarah Thomas is a contributor to the Weekly. Fresh from Milwaukee, she spends most of her time in coffee shops with comic books, and her interests include the arts, social justice, climate change, and Black feminism. She last wrote for the Weekly about a panel on growing up on the South Side.