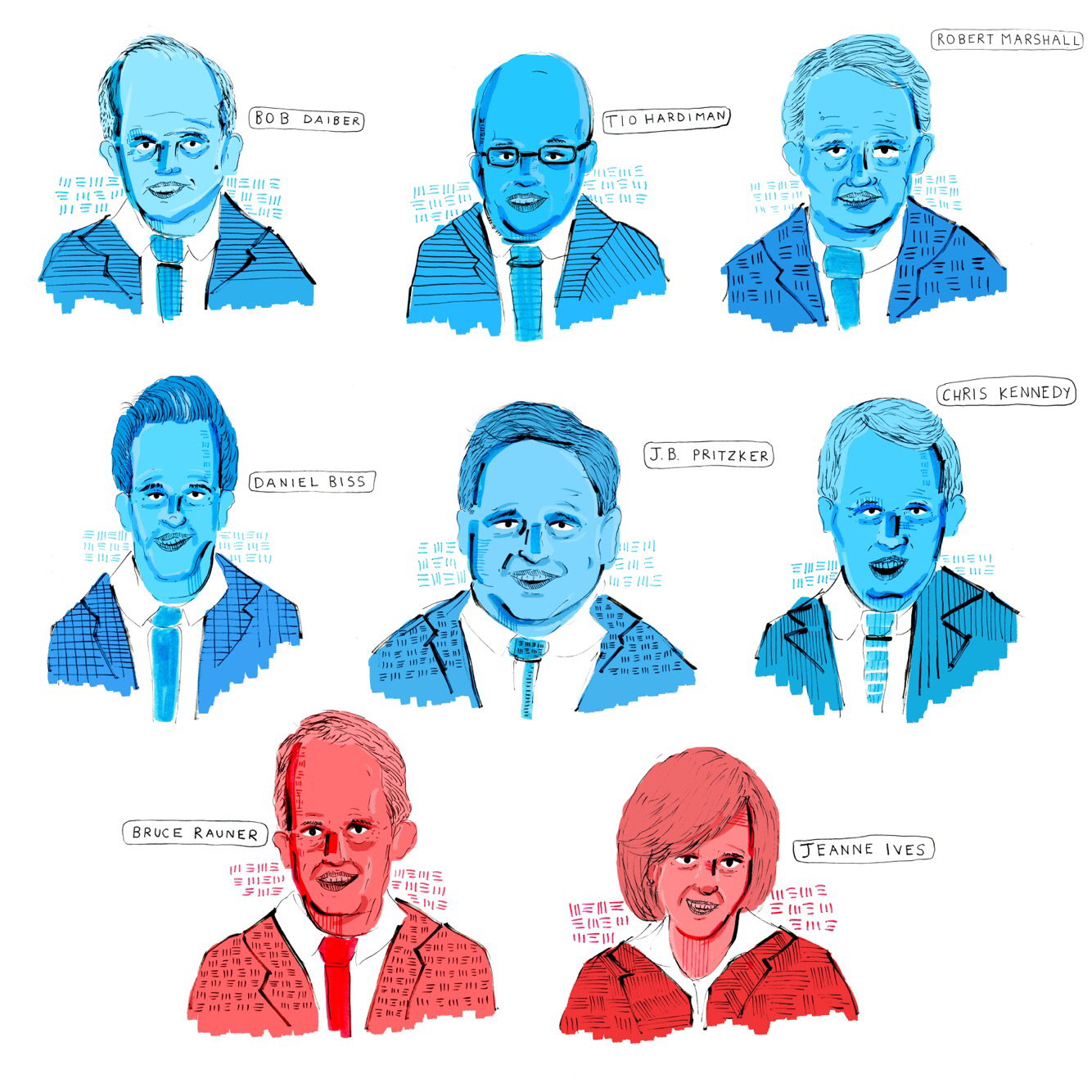

Republican Candidates

In the Republican gubernatorial primary, the “Insurgent” vs the “R.I.N.O.”

While Chicago is rightly understood to be a Democratic stronghold, Republicans live and vote here as well. In the profiles below, the Weekly explores the platforms of the two Republican candidates for governor, incumbent Governor Bruce Rauner and three-term state Representative Jeanne Ives. The Weekly also reached out to ward committeemen from the Central Committee of the Chicago Republican Party, who shared their opinions on the two candidates. The Republican gubernatorial primary will be Tuesday, March 20. (Michael Wasney)

Jeanne Ives has fashioned herself into the “insurgent” Republican candidate of the 2018 Illinois gubernatorial election, challenging an incumbent who many in the party have come to see as a turncoat. She’s a vocal supporter of Trump––and critical of Bruce Rauner for not being the same.

Unlike Rauner in his first electoral go-around—or Trump, for that matter—Ives is no political outsider, having represented the 42nd district (Wheaton in DuPage County) in the Illinois House since 2012. Before that, she graduated from West Point and served in the U.S. Army. Both her military background and track record in the General Assembly have swayed a number of Illinois conservatives and political action groups to her cause.

“I’ve been [a state representative] for five years, and I’ve been fighting for taxpayers,” Ives claimed in her introductory remarks at the debate hosted by the Tribune’s editorial board. “That’s why [Taxpayers United for America] endorsed me over a sitting Republican governor, because they know I’m going to fight for taxpayers.”

Republican Committeeman Rich Munnich of the 16th Ward endorsed Ives for her “conservative voting record,” and also because she was a graduate from West Point—“a positive thing,” he said.

Ives’s voting record shows that she opposed many of Rauner’s fiscal policy decisions, including Senate Bill 9, which instated a $5 billion hike on income tax, and Senate Bill 1947, the 2017 education overhaul bill that allocated money to schools in districts where property taxes were insufficient sources for funding. Her take on social issues are similarly in step with her party’s traditions: she criticized the Illinois Trust Act, which afforded some protections to immigrants, and voted against House Bill 40, which allocated taxpayer money to fund abortion services. Her adherence to traditional conservative values—and Rauner’s perceived divergence from them—has been a mainstay of her campaign.

Though Ives’s political history has been a selling point for many Republicans, her voting record has alienated others, like 12th Ward Republican Committeeman Antonio Mannings. Mannings took issue with Ives’s opposition to a bill that required schools to teach cursive writing—what he took to be a lack of commitment in his daughter’s education—and another that prohibits businesses from requesting the salary and employment history of their job applicants. Mannings supported the latter because he thought it would protect people who “can’t earn a higher living wage because they’re now disclosing a salary history that was lower.”

Her campaign, like her voting record, has caused some rifts among Illinois conservatives. In early February, she released an ad that castigated Rauner for being a traitor to the Republican party. It did so by depicting a series of liberal caricatures thanking Rauner for aiding their cause: among them, a Black Chicago Public School teacher thanking Rauner for the “bailout” he supposedly gave to their pension fund, a woman in a pink “pussyhat” thanking Rauner for an abortion she received on the taxpayer’s dime, and a transgender woman (notably, played by a cisgender male actor) thanking Rauner for letting her use the girls’ bathroom.

Even those within her own party called the commercial racist, sexist, and transphobic. GOP state chairman Tim Schneider also asked that her campaign take down the ad on account of it being “an attempt to stoke political division.” These admonitions did little to deter Ives, who maintained that it “properly and truthfully characterized the extreme issue positions Rauner took and their implications.”

Still, this traditionalist rhetoric appeals to some of her conservative constituents in Chicago. 8th Ward Republican Committeewoman Lynn Franco was one of them, having said that she likes Ives’s brand of moral orthodoxy, calling her a “salt of the earth type of person.” Franco added that she was attracted to Ives as a candidate because “she appreciates all of this, what this state has.”

The ghosts of Governor Bruce Rauner’s first term haunt his 2018 primary campaign. After a pension crisis, a two-year budget standoff, and few concrete accomplishments to speak of, it seems as if Rauner has few supporters left in Chicago. In a January straw poll held by the Central Committee of Chicago’s Republican Party, only three of the twenty-two Republican Ward Committeemen who voted endorsed Rauner.

Rauner won the 2014 gubernatorial race as a political outsider with a forty-four–point agenda he promised would “shake up Springfield.” Unfortunately for Rauner, Illinois House speaker Michael Madigan and a General Assembly dominated by Democrats proved to be formidable opponents.

Rauner’s political woes reached a head last year when, in an insurrectional moment, various Republican lawmakers sided with Democrats to override Governor Rauner’s veto of a $5 billion income tax hike. This effectively brought Illinois’s two-year budget impasse—the longest suspension of a state’s budget since at least the Great Depression—to a close, but it also incurred the ire of the governor’s own party. At the standoff’s end, Illinois was left with a heap of backlogged bills amounting to $16 billion and a credit rating lower than any other state in the union.

Many Republicans who backed Rauner in his first campaign have no desire to support his second round, though others maintain that Rauner is still the best for the job.

Rauner, for his part, paints his second campaign as a crusade to fix corruption in the state’s government. “[This election] is about taking power back from the corrupt insiders and giving it back to the people of Illinois,” he said at a debate hosted by the Tribune editorial board. “And we’re going do that this election by having the people of Illinois ask all the candidates in office to support term limits.” The issue of term limits has been a touchstone of this campaign, and one of the first points he made at the Tribune debate.

But Rauner’s rhetoric of new beginnings has done little to convince disillusioned Republican Ward Committeemen, particularly those who find his fiscal missteps to be dealbreakers. Critics have characterized Rauner’s failure to stave off an income tax hike as a particularly ill-advised concession.

“[Politicians] just take, take,” said Franco, adding in disbelief that a Republican in office would “cave into that.”

In an interview, Munnich called Rauner a “RINO”—a Republican In Name Only—and charged him with “essentially betray[ing] Illinois voters”.

Munnich and Franco were dissatisfied not only with the governor’s fiscal policy, but with his social policy: they disapproved of the Illinois Trust Act, which Rauner signed into law in 2017 and which Munnich said makes Illinois something of a “Sanctuary State”; House Bill 1785, which makes it easier for transgender people to alter the gender listed on their birth certificate; and House Bill 40, which allocated taxpayer money to fund abortion services.

The few committeemen supporting Rauner think it’s unfair to expect he’d fix all of Illinois’s woes in a single term. “We are dealing with a behemoth,” said 4th Ward Republican Committeeman Lori Yokoyama, in reference to the state’s government. “It’s not going to take four years to solve.”

Mannings agreed. His belief in the naturally glacial pace of government has kept him steadily in the Rauner camp: “I did vote for him last term, and my views have not changed. I understand the job he was coming into, and that it does take time, especially when you’re working with institutional change.”

Democratic Candidates

Among a variety of progressive platforms, differences in background and political priorities set these candidates apart

The Illinois governor’s race is heating up, with the Democratic primary election just around the corner on March 20, 2018. The race is, as of yet, too close to call. Many of the candidates share similar progressive platforms: staples such as environmental efficiency and a living wage characterize the majority of the campaigns. As such, background, electability, and political priorities may likely be the deciding factors in the primary. Early voting has already begun, so check your registration, find your polling place, and make it to the polls. (Juhi Gupta)

J.B. Pritzker, 53, the current frontrunner in the race, is a well-known billionaire with ties to establishment politicians (including, but not limited to, 2016 presidential candidate Hillary Clinton.) A recent poll featured in the Tribune shows Pritzker leading with thirty-one percent support, beating Biss by a margin of ten points. Heir of the founder of Hyatt Hotels, Pritzker cofounded a Chicago-based investment firm with his brother, dealing in venture capital, private equity, and asset management. He also spearheaded a tech business incubator.

But Pritzker falls short when it comes to political experience. Despite being the wealthiest candidate to ever run for governor of Illinois, Pritzker resists the narrative that Illinois doesn’t need another “rich guy.” He speaks to his values as evidence he is committed to the success of the working and middle class. These progressive values don’t seem to show up in his investment portfolio, however: his filings show investments in the Dakota Access Pipeline, casinos, and Big Oil. Pritzker also fell under fire after an FBI wiretap revealed him making racially insensitive comments in conversation with convicted former Illinois governor Rod Blagojevich.

Much of Pritzker’s literature focuses on resisting the Trump presidency. This resistance, for Pritzker, consists of enacting policies to protect Illinois from federal assaults on healthcare, education, the environment, immigration, and civil rights. He believes in providing a public option for healthcare, focusing on and funding early childhood education, and putting Illinois on the path to one hundred percent renewable energy. He emphasizes investing in local entrepreneurship and talent, especially through making Chicago the technology hub of the Midwest. Much of Pritzker’s own work in the private sector focuses on developing entrepreneurs and new business, and his campaign rhetoric stresses his history of job creation in the state. His plan for rebuilding disinvested communities follows naturally from there: it’s focused on business development and infrastructure for job creation.

Chris Kennedy, 54, son of the assassinated Senator Robert F. Kennedy (D-NY) and scion of a well-established political family, has never run for office. After getting a master’s degree in management from Northwestern University, he worked in a variety of industries: real estate, manufacturing, nonprofits, and finance. Despite his liberal brand, Kennedy’s investment portfolio shows some surprises: his required filings for gubernatorial candidates show investments in military defense, Big Tobacco, and Big Oil.

Currently, he and his wife run a hunger relief nonprofit that delivers food to underserved neighborhoods, and he previously served as Chairman of the Board of the Greater Chicago Food Depository, the nation’s leading nonprofit food distribution and training center. Kennedy served as chairman of the University of Illinois Board of Trustees for six years, overseeing a $5.5 billion budget.

Kennedy’s platform focuses on the economic revitalization of Illinois through job creation and business development. Kennedy has aimed his economic strategy toward developing a high quality workforce, an environment that facilitates the development of new business, and a commitment to innovation. He wants to increase state grants, invest in long-term economic planning, use Illinois universities and business incubators as hubs for economic development, and encourage minority and women entrepreneurs. Along with this, he has a history of supporting organized labor: he vehemently opposes union-busting right-to-work legislation and has a history of hiring union workers at Merchandise Mart and his real estate development in Chicago, Wolf Point.

As someone whose family has been “deeply impacted by gun violence,” Kennedy has a robust plan for addressing crime. It consists of creating economic opportunity in disinvested communities, strengthening gun laws, providing trauma and mental health services to communities, and investing in community policing and restorative justice programs. He believes in a single-payer healthcare system and supports decriminalizing marijuana. Kennedy disapproves of tax breaks for major corporations, such as Amazon, in favor of investing in research institutions and higher education to spur economic growth.

Daniel Biss, 40, current Illinois state senator (D-9), is the only contender who has served in the Illinois state legislature. After getting a PhD in math from MIT in 2002, Biss worked as an assistant professor at the University of Chicago, before focusing his sights on state politics. With the backing of pro-Bernie giant Our Revolution and a multitude of small grassroots donors, Biss has catered to the everyday Illinoisan with rhetoric condemning the state’s history of machine politics and corporate greed.

He is running under the banner of the only “middle-class governor,” supporting legislative action to increase the minimum wage to fifteen dollars and fully funding higher education. Despite backlash from the left after dropping 35th Ward Alderman Carlos Ramirez-Rosa early on over his views on the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions campaign against Israel, Biss is steadily gaining on Pritzker despite raising only a fraction of the money.

Biss’s campaign has foregrounded his voting record: he has successfully led bills to increase retirement savings and ban LGBT conversion therapy, and has sponsored bills ranging from expanding Medicaid eligibility to increasing the minimum wage. Other votes range from prohibiting the screening of job applicants based on salary history, directing public funds towards higher education, and requiring health insurers to cover birth control.

He intends to fight mass incarceration through a “FAIR” approach to justice, which includes ending for-profit policing, legalizing marijuana, focusing on police accountability, removing bars to employment for returned citizens, and reforming the Illinois sentencing system. He doesn’t believe in providing tax breaks to major corporations due to the negative effect on residents and small businesses. He stresses public reinvestment in low-income communities of color in order to slow African-American population decline and create economic growth. He also wants to put Illinois on track to one hundred percent renewable energy.

Dr. Robert Marshall, 73, is a physician from Burr Ridge, Illinois. He has a history of political ambition: he ran for Congress in the late nineties as a Republican, for U.S. Senate as a Democrat in 2010, and again for Congress as a Democrat in 2016. Marshall is the odd one out of the candidates. For one, he is the only candidate that does not support a graduated income tax. In fact, Marshall is against all tax increases, and he believes that higher-income residents of Illinois shouldn’t be taxed more just because they are, he thinks, working more and harder.

When asked if transgender students should be allowed to use the bathrooms that match their gender identity at the Democratic gubernatorial forum held at the University of Chicago, he was the lone candidate to say no. One of his more unique policy proposals is the division of Illinois into three states, each with their own tax structure and governor. These states would be divided along the lines of Chicago, the suburbs, and downstate. The rationale behind this policy is that the division would benefit state-level issues like the budget and pension debt. Marshall also strongly believes that the primary way to reduce crime and gun violence is taking money out of the drug trade. He wants to decriminalize marijuana, cocaine, and morphine, which he believes will also reduce the decline of Illinois’s African-American population.

Bob Daiber, 61, has thirty-eight years of experience in public service and a strong background in education. He currently serves as regional superintendent in downstate Madison County. Daiber also has roots in agriculture and a history of regional planning for residential and business development: he’s served in the past as a township supervisor and a county board representative.

As the son of a Teamsters member, Daiber purports to speak for the middle class of downstate Illinois, which he believes won’t be adequately represented by a native Chicagoan governor. He believes that his experience in local government sets him up for success in the Illinois state legislature. Due to his background, he places a high value on organized labor: he pledges against right-to-work legislation and wants to maintain the rights of workers to bargain collectively.

Notably, Daiber is the only candidate who has laid out a graduated income tax plan with specific figures. He believes in fully funding public education through this progressive income tax and establishing community health care centers. Despite frequently mentioning that education is his top priority when it comes to addressing broken systems in Illinois, he neglects to mention urban school district issues in Chicago, such as recent high school closures. His focus on education is primarily on funding at the federal level. His policy recommendations for reducing crime are fairly scarce: he believes in reducing sentences for imprisoned felons to combat mass incarceration, establishing school and community programs to deter youth from crime, and providing “needed support” to law enforcement officials.

Tio Hardiman, 55, is the only person of color running for governor. Raised in Chicago, Hardiman holds a master’s degree in inner city studies and teaches as an adjunct professor of criminal justice at Governor State and North Park Universities. He previously ran for governor in 2014, securing thirty percent of the vote in the Democratic primary, but lost to incumbent Pat Quinn, who went on to lose against Rauner.

His “20/20 Vision” plan focuses on levying a tax on transactions at the Board of Trade and Chicago Board of Operations Exchange, reducing violence and reforming the prison system, increasing the minimum wage to fifteen dollars, and investing in economic development. Violence reduction is Hardiman’s campaign focus, and the area he has the most experience in. One of his campaign promises is to reduce violence across Chicago and the state of Illinois by fifty percent.

Hardiman served as the director of CeaseFire Illinois, a notable community-based violence prevention program piloted in high-crime neighborhoods, for fourteen years. Hardiman piloted the Violence Interrupters initiative while he was with CeaseFire Illinois, using community members for conflict mediation and violence intervention in crime-ridden neighborhoods.

The program has largely been considered a success, despite its closure due to budget cuts. Pritzker lauded the program in the Democratic gubernatorial candidates forum hosted at the University of Chicago at the beginning of the month. Hardiman also wants to reduce recidivism through converting prisons to institutes of higher education. His two-pronged approach to reducing gun violence is first to reduce illegal gun trafficking, and second to create violence prevention programs, send officers into underserved neighborhoods, and provide services and opportunities for at-risk communities.

Support community journalism by donating to South Side Weekly

I think the overall information presented here was informative and will allow me an opportunity to vote not alone party lines, but for candidates that reflect the changes and programs that will benefit me, and my community at large.

I now believe that the candidate who earns my vote has a real plan, believe in programs that work, understands that they work for the people, and not for themselves.