Lucy Parsons Labs, a Chicago- and San Francisco-based nonprofit that works toward more transparency in government and business, first gained attention in 2014 for its use of public records lawsuits to uncover the Chicago Police Department’s (CPD) undisclosed purchase and use of Stingray cell phone surveillance devices. In addition to concerns about surveillance, a 2016 investigation the nonprofit published with the Chicago Reader lent visibility to the CPD’s controversial use of civil asset forfeiture, the process by which police can seize money or goods they believe are connected to a crime. The CPD drew from its civil asset forfeiture funds to purchase the Stingrays and other surveillance equipment, their investigation found.

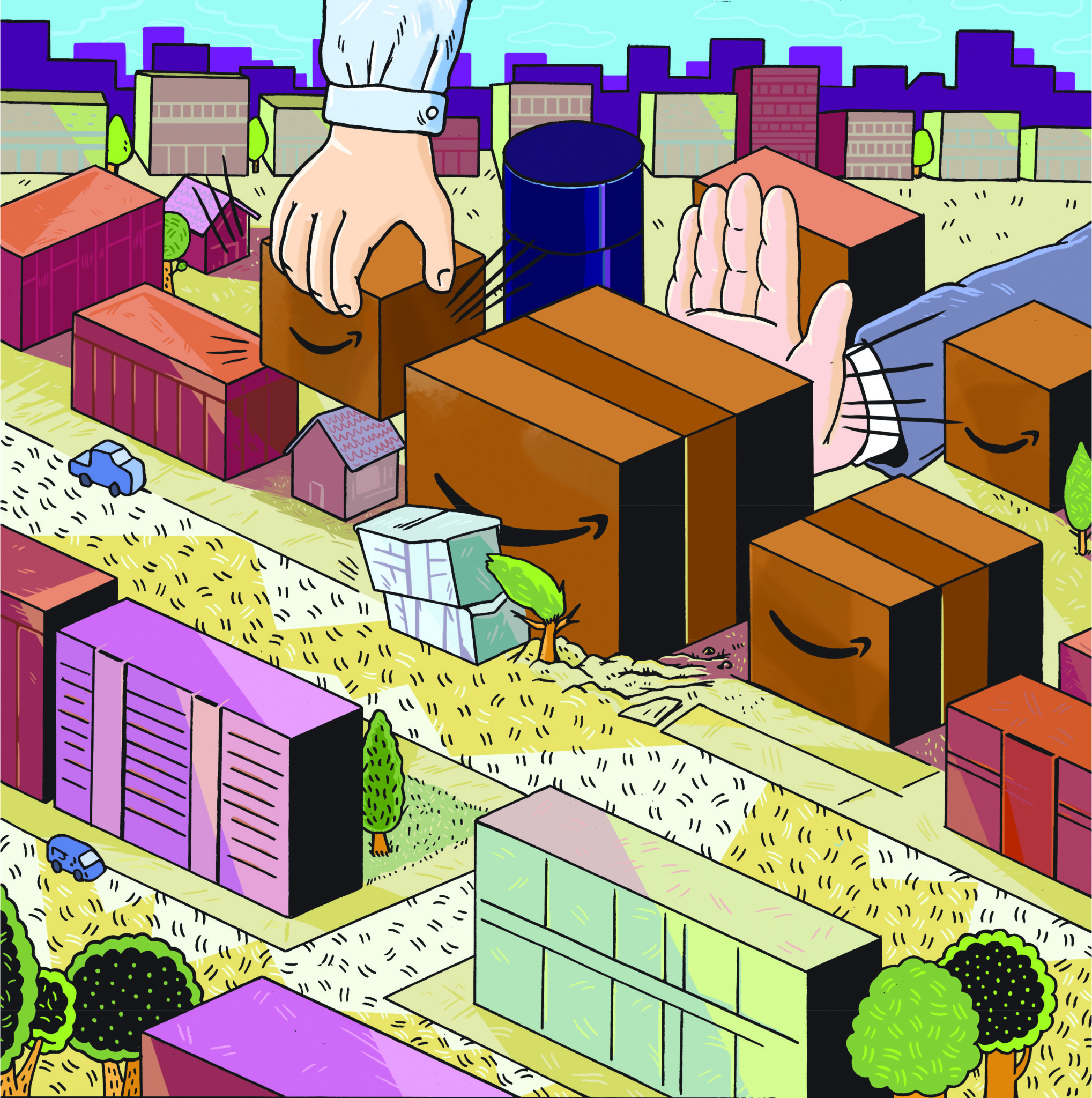

In recent months, Lucy Parsons Labs (LPL) is back in the spotlight with a new lawsuit against the city over its refusal to release its bid to Amazon for HQ2, the tech giant’s second North American headquarters. Several cities have released their bids, which are available on the public records site MuckRock. The Weekly spoke with LPL director Freddy Martinez over the phone to find out more about the suit and what HQ2 could mean for Chicago. This interview has been edited for space and clarity.

How was Lucy Parsons Labs founded?

In about 2015, we started doing [public records] requests around this invasive surveillance equipment [Stingray] that was owned by the police. We were able to prove that they were using it, and we were able to prove that they were not getting warrants. They had no policies or procedures for handling the surveillance equipment. From there we just kind of kept building steam, and that’s how [LPL] came to be. I had a lot of friends and colleagues who were also interested in the topics that we were pursuing, so that’s how the group was formed. Before the nonprofit, there was a group of us working informally, and then we just formalized it.

Why did you decide to sue the city for the details of its HQ2 bid?

We read about some of the details of the city’s bid for HQ2 and learned that people who were employed by Amazon would pay taxes to Amazon instead of the state, which is a very strange thing. [Ed. note: A mayoral spokesperson reached by CityLab in November on this issue refused to confirm or deny specifics of the bid.] After reading lots of things like this we decided to file suit. We also saw that MuckRock, which does a lot of public records requests, was trying to get Amazon bids across the country. So we decided to join and try to get the Amazon bid from the city of Chicago.

The city is trying to claim an exemption under section 7(1)(h) of FOIA1, which applies to proposals and bids for any contracts filed with the city, even though the HQ2 bid involves a bid the city has filed with a private corporation. Why might they try to cite that exemption if it doesn’t seem to apply?

One thing that’s particularly curious about public record requests is that a lot are filed by corporations. They do it because if you know how much your competitor bids on a particular service, then you can undercut them. This exemption is about making it so that proposals or bids for contracts are not released before a final selection is made. So it really applies to services that the city is going to provide. But this is a proposal that the city is putting out, offering its services to a private corporation. Our argument in court will likely be that the exemption is being misapplied, because the information is presumed open except for in a very limited case. We think that the city is trying to expand the scope of this exemption. That also applies to proposals that haven’t already been submitted—the city has already sent Amazon their bid, so it’s not like if it was made public, it would change anything about the proposal the city has already made. So for them to claim that it’s exempt because the final selection hasn’t been made is a bit strange.

Apart from that issue, could you tell me a bit more about what you’re hoping to uncover or achieve with the lawsuit? What would be an ideal outcome for you?

We really see this lawsuit as part of a broader socioeconomic problem in the city of Chicago. The CHA has [tens] of thousands of people on public housing waitlists, CPS is closing schools for what they claim are budgetary reasons, the city closed half the mental health clinics. So the city cries poor on the one hand, and on the other hand tries to give out massive corporate welfare at the expense of essentially the entire city of Chicago. For me personally, I think the ideal outcome would be to invest the two billion dollars that they’re trying to give away into things like housing, education, and public transportation. [Ed. note: this figure reflects the city and state’s combined bid.]

But with this bid in particular, I think it’s really important that the details not be secret. Look at the history of how these corporate giveaways look. Foxconn in Wisconsin isn’t going to break even for a hundred years, and that assumes that Foxconn as a company exists in a hundred years and that the jobs haven’t been automated away. Tesla wanted to build a factory and kept pitting cities against each other and eventually got more than a billion extra in giveaways. So keeping this secret is only going to harm Chicagoans in the future, because what the secrecy really does is pit cities against each other in this almost Hunger Games style where it’s about how much you can give away to Amazon. We should also bear in mind that Amazon is one of the richest corporations in the world. They don’t pay any federal taxes; they don’t need any money from us.

Support community journalism by donating to South Side Weekly

If the bid were released, do you think public opinion would turn against Amazon?

It’s hard to say. When it comes to these large powerful institutions, you’d like to think that one small action can have a real impact. But I think Lucy Parsons Labs has had success in doing investigations and activism to actually have an impact, so I’m hopeful on that front. There has been an uptick in stories in which people talk about the issue of giving a bunch of money away to Amazon, so I’m hopeful, because it does seem like there’s more of an interest in this now.

In an interview with MuckRock, you said, “Secretive bidding is really a race to the bottom for communities.” Could you expand on that? And if that’s true, why would the city be so hesitant to release the bid?

As I mentioned earlier, the real long-term interests for building high-quality jobs and the kinds of things that make a good workforce are the things that cities should be investing in now, like good education, infrastructure, and healthcare. But the opposite is happening. You’re front-loading these massive giveaways and asking someone to come in and use all your infrastructure.

I think the secrecy here is frustrating for a number of reasons. People who work at Amazon might not even know that their taxes are being diverted to Amazon and not to the state of Illinois, but that’s something that they should know. You also see weird giveaways that other states have tried to do: in one case, they wanted Amazon to own part of the town. If you put all of these things in aggregate, you can see that because everyone participates in this secrecy, everyone’s getting scammed together. These are recurring themes. But it’s not surprising to me, because, again, it seems like the mayor’s office is only interested in providing for a small segment of the population.

Comparing the proposed South Side sites—the Michael Reese Hospital in Bronzeville and the Rezkoville lot north of Chinatown—with the other proposed sites, the majority of which are North Side or downtown sites in affluent or gentrified areas, it seems like there are different stakes here for the South Side communities that would stand to be affected.

Many of the sites are on the North or Near North Side. It’s not surprising that the majority of them are near well-developed and well-off areas. On the other side, there are very few on the South Side. It’s really not surprising because if you look at the process of development in the Cabrini-Green area for example. I went to high school near Cabrini-Green, and I go back there and don’t even recognize it. If you think about it in the broader context of gentrification, we already know that the proposed Obama [Presidential Center] is going to be pushing people out, it’s already driving housing costs through the roof in those areas. So you think about it in that context; the housing that might get proposed on the South Side, it’s not for [current South Siders]. Those decisions are being made about people but not with them. I think it will probably lead to very rapid gentrification and displacement of long-time Chicagoans.

Along those lines, what effect do you think HQ2 would have on the demographic geography of the South Side?

If you look at the history of examples like Seattle, San Francisco, or Oakland right now, you can see a very rapid demographic shift. For example, in Oakland, there was a study done that showed that most people that leave the area are long-time residents. Another study showed that the people who come into the area make around $12,000 a year more than the people who are leaving. I really do think history will show that Amazon will not destroy, but rapidly change the experience of living in Chicago. Chicago is one of the few major cities that has reasonably affordable housing. Even in Chicago it’s not affordable—you can’t live on minimum wage and afford a two-bedroom apartment. But the cost of housing is still about fifteen percent lower than Seattle. And I don’t think that that’s going to stand if Amazon tries to come into town.

Something that ties a lot of the projects you’ve been involved in together is a focus on invasive surveillance technology. Does that concern carry over to this specific lawsuit and Lucy Parsons Labs’ interest in Amazon as well?

Yeah, absolutely. One of the ways that gentrification works is that there’s massive overpolicing of communities that are on the borders. It’s a very neocolonial way of dealing with the population. This happened in the public housing units, it happened in Oakland. So we have done a lot of work on policing and police transparency, and we expect that that’s going to be the model of clearing the land. We see it as part of a bigger systemic issue of how you get people to leave their homes if they’re not willing to go. A nice way of doing that is just locking them all up in jail. So we do think about it—that’s likely a thing that will happen, and that’s a pretty massive concern for us.

1. Section 7(1)(h) of the Illinois Freedom of Information Act allows a public body to redact information related to “[p]roposals and bids for any contract, grant, or agreement, including information which if it were disclosed would frustrate procurement or give an advantage to any person proposing to enter into a contractor agreement with the body, until an award or final selection is made. Information prepared by or for the body in preparation of a bid solicitation shall be exempt until an award or final selection is made.”

Rachel Schastok is a contributing editor to the Weekly. She’s back in Chicago after a couple years working as a translator in Spain. She last wrote for the Weekly about photographer Todd Diederich in February 2015.