At about six in the evening, sculptor Elena Ailes slips out of her black pickup, key ring in hand, and leads me through a locked alleyway. We pass through an oppressively normal Kimbark backlot, where a single drip of hardened terracotta plaster dots the grass like a telling bloodstain, guiding us down into the hidden subterranean gallery known as the 4th Ward Project Space. Below the earth, we talk about plants.

“On Being Sessile,” a sculpture exhibition by School of the Art Institute of Chicago master’s student Ailes, studies the idea of active rest. “Sessility” is a biological term about two things: immobility and grounding. It has botanical implications: a flower, for example, is sessile if its petals are directly attached to its stem—grounded to both itself and the dirt. For Ailes, however, sessility extends beyond plant life. It also applies to humans, objects, and everything in between.

“The work comes around ideas of stillness, sleeping, and the worlds that are contained inside our worlds—like when we’re dreaming or lucid dreaming,” Ailes said.

Her work explores what happens when creatures or objects experience that immobility—not just “sessility,” but being sessile. Even plants, though forever stuck in the soil, are living. They experience metabolism, growth, and activity. Oysters and coconut seeds, Ailes explained, can travel quite far throughout their lifetime, carried along by the ocean and the wind.

I didn’t think it possible, but the small, whitewashed basement gallery was even smaller than anticipated. A sparse array of isolated forms scatters the space. They range from simple wood frames to metal sheets. But the room, devoid of color and life, is missing something.

“There’s actually a plant that’s supposed to be in here. It’s upstairs in an apartment right now because it’s too cold, but it’s the inspiration for a way of thinking that the work kind of ‘stems’ from,” Ailes laughed. “That’s a bad pun…”

Ailes gave some background on the absent form:

“When I was a kid, one of my neighbors happened to grow it in a greenhouse—the Cup of Gold vine, or the chalice vine (Solandra maxima). I found out a couple years ago from another artist, Beatriz Santiago, that when they bloom, they produce a pheromone that we release when we’re falling in love or having sex. I was caught by the idea that one reproductive cycle and another reproductive cycle that don’t have anything to do with each other still have these accidental overlaps.”

Part of the nightshade family from Central America, this psychotropic vine is a hallucinogen (no, Ailes has never tried eating it), and though the plant installed in the exhibition has since branched away from its original roots, botany remains a grounding influence. In the center of the room stands a dismembered bedframe, oriented vertically. Ailes has woven thin white rope across it—more trellis than bedsprings. The string, however, thick and wound, appears nautical, and the woven pattern, an orthogonal grid, more closely resembles modern design dogma than an organic fence.

The trellis’s severed limb, a wooden headboard, leans against a nearby wall. The sculpture itself is tight, yet altogether uninteresting—save for Ailes’s choice to manufacture a plastic shadow on the wall behind the frame. The “shadow” doesn’t actually exist, but, perhaps in another dimension, it could.

“It’s a rupture—kind of a surrealist experience, right?” Ailes said. “It becomes a world inside a world, which is how I think about lucid dreaming, or even how we exist together. It’s just a…proposition to another world, creating its own special reality. As a viewer, it’s not a logic that I live, but it is actually what I see.”

If we take the severed bedframe as a comment on sleep as a human’s most plantlike, sessile state, and a nod to the different worlds contained in that state, then Ailes’s metal sculptures on the opposite half of the gallery act as a related, though alternative, departure: a meditation on sculptural material.

Speaking of sessility, Ailes said, “For me, this translates as a type of attentiveness, especially to material. I push against the world and the world pushes against me. That’s where that material intimacy comes from. This piece, these are lead sheets, and maybe on a political or chemical level they push against our bodies in a way. But in this work, they’re embossed, with a wallpaper pattern that I redrew from memory—some crazy Japanese wallpaper that was in my grandparent’s house.”

The way Ailes speaks about her creative process, it’s almost as if she views herself as a sculpture too. In these lead works, two thin sheets lie folded across a raised lead bar while a crystallized pool of the same medium sits in a puddle below: point and counterpoint. The folded pieces, Ailes explained, are an expression of sculptor’s manipulation. To cut and to emboss, Ailes physically pressed herself against these sheets. The pool below, however, is lead-free and uncorrupted. This is the substance, the metal itself—the material that presses against her in life.

This lead piece is perhaps the most successful element of Ailes’s exhibition. It hits on sleep in its exploration of state, dimension in its structure and folding, and botany in the floral curves of the Japanese print. It’s far subtler than the trellis frame, elegant, and precise in concept and execution.

“This work, for me, feels like sculpture with a capital ‘S.’ I have often made work that is more text-based or more language-based, even in my sculptural work. There’s something about the formal singularity of it that feels really right. Making sculpture means that I’m in relationship with these materials. We’re being slow together—you can’t rush any of these things even if parts happen quickly, like pouring metal on the ground. Everything takes its own material time,” Ailes said.

Beyond attention to medium, Ailes was keenly sensitive to the basement where she worked, detecting the structural nuance of the earth and cultivating art to match. In a far corner where a pipe strikes the ground, a divot has formed in the grey concrete. Rather than overlook this spacial subtlety, Ailes feels out the floor’s variation by filling in the dip with tiny copper spheres, almost as if water droplets have gathered there in a pool. This piece lies a mere two feet from the lead sheets. While the lead imitates nature on a conceptual, and physically larger level, the copper spheres break nature down to its minuscule components, mimicking its forms.

“Normally, people who make sculpture want there to be lots of space around these autonomous objects that you experience in 360,” Ailes said. “But because it’s so small, I almost put more work in here than I normally would have so that you experience this other kind of ‘pushing.’ Only two feet between sculptures, tiny things tucked in the corners, a random piece of gum, an eyelash—these things that are able to be both super small and super big just because it’s the space.”

Despite her preoccupation with state and immobile activity, Ailes actually inhibited her own pursuit of the sessile. Take the slice of the flowerpot on the floor beneath the gallery’s lone window: it’s the iconic gardening pot—sienna plaster—but now Ailes has filled it to the brim with plaster. It looks like a shabby job, overflowing slightly with scattered white patches. There were initially three of these sculptures, but due to the extreme temperature variation in the basement, the pots began to expand and contract, cracking and discoloring.

“They were these perfectly made sessile objects, and here they are with a life of their own,” Ailes said.

Ailes decided to remove two pots and reconfigure the third. She attempted to manufacture growth—the pot’s “metabolism”—when a more hands-free approach would have been far more effective in the scope of the exhibition’s themes—and she knew it. It’s the paradox of a degrading perfectionism.

“I have to set myself up to work with blinders on—to let the materials speak for themselves and make stuff on accident,” Ailes said.

Above it all, and almost invisible, three delicate shuttlecocks perch among the rafters. Ailes crafted each from the feathers of significant birds in her life: a vulture she hit with her car on the highway in Ohio, her friend’s shedding parrot, and the crow another friend found dead in her backyard (in spirit only for the last—she actually had to order feathers online).

“These are the hardest thing for me to talk about. I used to say I loved them because they’re self-orienting objects. You know, when you’re playing, they turn themselves around—operate on their own logic,” Ailes said. “From a bird’s eye view, I think of our collective exhaustion, and that’s our shared state.”

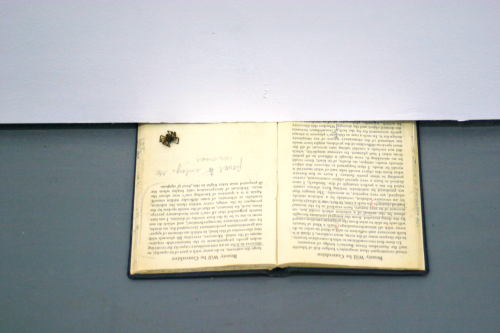

Ailes spoke extensively of her own fatigue: beaten and wedged between worlds like the library copy of André Breton’s book What is Surrealism?, discreetly tucked beneath a wall. Though “On Being Sessile” is not a surrealist exhibition itself, Ailes chose to incorporate this text, topped with a dead spider, to import yet another layer of sessility. She also just happens to be a fan.

“I often think that as an artist, I am myopically zoomed in on my own life but also zoomed out ten times by ten. The past few years for me have been marathon living: working and thinking and working and thinking. It feels like, now, there’s this weird antagonism in the world. Like we’re all on top of each other in a way that doesn’t stem from empathy—politics, race in Chicago, the global climate crisis. Even on a personal level,” Ailes said.

“We’re asked to do so much in the course of our days—to sprint around performing all this mental and physical labor. Turning ourselves inside out to work and make our work and make our way. Sometimes we need to turn our brains off—and I think that makes for good work.”