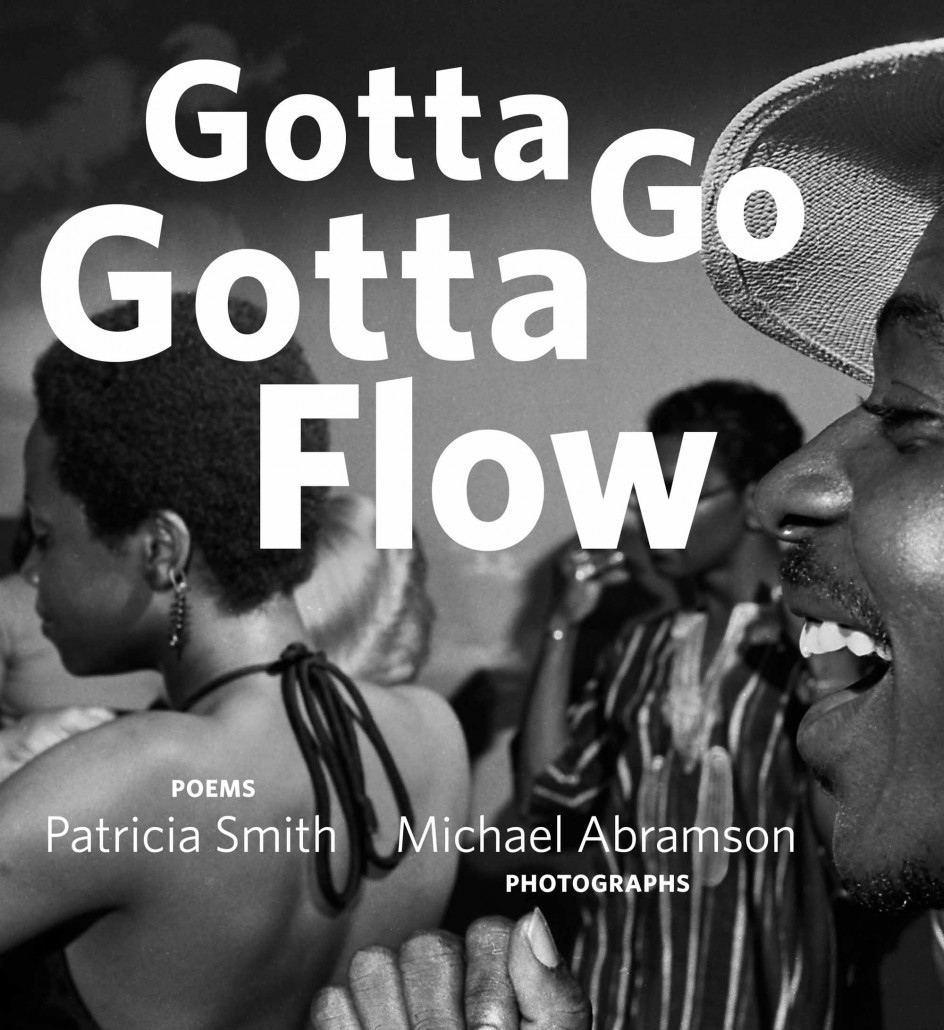

Your body was crafted for this,” writes poet Patricia Smith, her verse stark and sparse against a white page, neighbored by a glossy black-and-white photograph of a man in rapture to music. Such affirmations fill the pages of Gotta Go Gotta Flow: Life, Love, and Lust on Chicago’s South Side, at once an exploration of the South Side’s nightlife in the 1970s and a celebration of the body in movement. It is also, in the wake of the artist’s passing in 2011, a rebirth of the images of Michael Abramson—referred to in the foreword as “that white boy lugging that camera again”—initially known for his documentation of Chicago’s urban life. While one cannot quite call Smith’s poetry in this book descriptive, the individual poems personify the pictures, bringing us into the souls of the subjects.

One image, for instance, depicts two women poised in their seats, arms waving to the music. Smith takes on their voices, writing, “We dance demurely in our seats/while waiting for partners.” By writing from their point of view, Smith gives us a glimpse into the inner lives of bodies in motion, the thoughts caught behind their furrowed expressions, the beads of sweat. They are no longer strangers to us; while the intimacy of Abramson’s camera brings us close to his subjects, Smith’s poetry provides us with the cadences of their voices and the pulsating rhythms of the jazz clubs depicted.

Smith’s accolades include two Pushcart Prizes, the Carl Sandburg Literary Award, and the Academy of American Poets’ Lenore Marshall Award. She is a four-time National Poetry Slam champion; her background in spoken-word clearly informs the tone and tempo of these poems, often foregoing floridity for the power of simple declarations. Take the interior monologue of a fur-coated woman whose back is turned to us, her cocked cigarette ghostly white: “I am not about/compromise/I am not about/negotiation/I am not about/discussion.” The musicality lies in her terseness, her repetitions, her proclamations.

Smith does not only rely on performance-inspired verse, however, often delving into different varieties of metric composition. Some poems even function like songs, using lines that invoke assonance and rhyme schemes such as, “You put a dip in your hip, you let your backbone slip/You keep your eyes on the prize and let his nature rise.” One could say the book is an exploration of different types of music, from thumping bass to slow jazz.

Above all, this collection of photographs and poetry illuminate the culture of a Chicago forty-plus years past. The pages brim with the modish fashions of the day—flared sleeves and plaid suits, miniskirts and tight pants—and conjure up the aura of not only a time but a place. The clubs of Chicago have a certain texture like no other locale, and through Abramson’s lens every grain is tangible, even the grime glistening. Every expression is caught at its most potent moment, from a singer in rapture mid-song to the dead-eyed gaze of a woman rejecting advances. Though these people are clearly and proudly of a different era, we can’t help but know them through the modernity of Smith’s words, often evoked through the power of the women’s voices, the sense of liberation from the male gaze. The photographs are relics of a different time, and the poetry recasts them in a contemporary and emancipating light. While Abramson may have taken his pictures with a sense of detachment as an outsider to this culture, Smith reclaims the narrative with her words, giving these figures’ thoughts an edge of authenticity.

“this is chicago/this is america. oh wait/this is/1 in the morning,” Smith says, in the voice of a wide-eyed girl staring off into the distance. These are the faces of a country, an era, and, perhaps most importantly, a city.