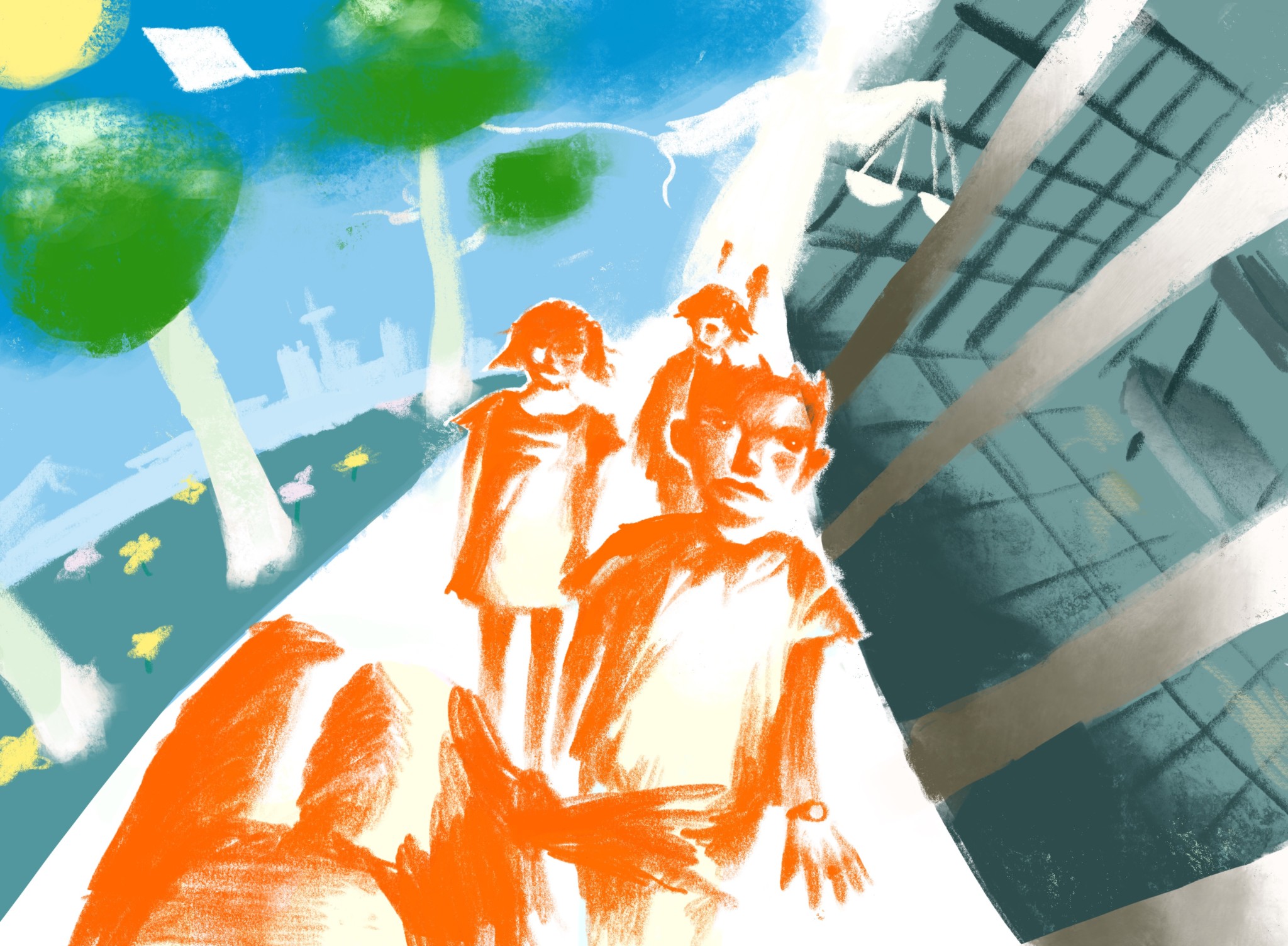

George Gomez, a thirty-five-year-old Mexican American, adores his beautiful daughter Nayelli. His mother Eloisa and sister Maria both love and support him, and he has brothers, nieces, and nephews. However, Gomez doesn’t get to spend the time with them that they would like. When Eloisa looks at him, she still sees the adolescent boy that she last remembers from before he went to prison. Maria still sees the little brother who never had a fair chance at growing up—and maybe never will.

Gomez, like many others and myself—I was incarcerated at age 19 in 2004—is caught in the in-between. No, this isn’t the upside-down of the fictional universe in the Netflix series Stranger Things, but a very real, strange thing, illogical to the point that it leaves you scratching your head. The in-between is a sort of purgatory that has left these youths languishing for decades. And without a few simple changes, it will continue to do so for many more. It’s a legal limbo in which some will not benefit from recent laws designed to offer parole to people who were convicted as young adults.

There are two legal barriers that make up the in-between. One was set several decades ago, and the other put in place more recently, and both are both simple and complex. Gomez, I myself, and thousands of other Chicago youth are caught in the legal limbo that lies between them.

The first barrier was set in place when then-President Bill Clinton signed the 1994 Violent Crime and Law Enforcement Act, otherwise known as the 1994 Crime Bill—which was most detrimental to poor and minority communities in its policies and enforcement, and which Clinton has since said he regretted. President Joe Biden has also expressed regrets over the 1994 bill and has vowed to do his best to put pressure on states to change it as well.

The 1994 Crime Bill placed financial incentives and political pressure on states to enact truth-in-sentencing laws (TIS) at the state level. The bill included $9.7 billion in funding for prisons. Within these incentives, there were also grants for states to enact tougher truth-in-sentencing laws. Illinois built nine new prisons in the 1990s. The 1994 bill only kept the ball rolling!

Illinois passed a TIS law in 1998 that meant that all convictions for violent crimes would result in very long—and sometimes, effectively life—sentences. Under the new law, Illinois changed the amount of time required to be served to between eighty-five and one hundred percent of a sentence, but not the range of the sentences themselves. Therefore, instead of a convicted person doing ten to thirty years for a murder, for example—which would average twenty-two-and-a-half years, from a range of twenty to sixty years, because sentences were indeterminate, meaning that with sentence reductions for good behavior in prison, aka “good time,” one might get out sooner—now, convicted people must serve one hundred percent of their sentences. There are no good-time allowances, and no adjustment for range.

Other states adjusted the range because they understood the ramifications of TIS laws, but Illinois apparently just didn’t care.

According to at least one study, people who are incarcerated and are released early for good time are no more likely to be convicted for crimes than their peers who serve their full sentence. Good time also gives people hope. It makes the Department of Corrections a truer definition of its role, correcting behavior! Without it, prison is just a warehouse for people.

The second barrier is simple, and yet a little more complicated. Think about your eighteenth birthday, or that of your son, daughter, niece, or nephew. Was there some magical button on that day that was pushed to make you or them a logical, responsible, mature adult? Absolutely not! This is why the drinking age is twenty-one: because being a mature responsible adult doesn’t come overnight.

That simple fact is where much of the science and the validation comes from in the 2019 youthful offender parole bill (730 ILCS 5/5 – 4.5 110 Public Act 100- 1182). This bill grants those who were convicted of a crime when they were under the age of twenty-one the opportunity to apply for parole after serving ten or twenty years of their sentence, depending on what they were convicted of. The law is far from perfect, but at least it opens the door for possibility in the future.

The law stems from research that was validated by the United States Supreme Court in the landmark case Miller v. Alabama, which found that the young mind is not done developing until around the age of twenty-five—specifically, the prefrontal cortex, which governs decision making, impulse control, handling volatile situations, and understanding and weighing consequences.

So this new law should help and not hurt, right? So then why would I call it a barrier? Because the law is not retroactive, meaning it doesn’t apply to those who fit the law’s criteria, but were sentenced before June 1, 2019, the date the law went into effect. So if you were under twenty-one when you were sentenced, on a date that fell between the installment of Illinois’ 1998 TIS law and June 1, 2019, you are caught in the in-between.

But why not make the law retroactive? For many years Illinois was at the forefront of juvenile justice, being the first state to set up a court strictly for juveniles. However, this would later lead the way to having an expansive juvenile detention system as well. That juvenile system, court and all, would see you through until— guess when? Until you were twenty-one years old!

Many people caught in the in-between, like George Gomez—who was not convicted of personally discharging a firearm in his case—didn’t actually harm anyone but themselves. TIS laws mean these youth were effectively given a life sentence even when they didn’t take a life.

Many of these youth have languished in prison for decades, rehabilitated themselves, and statistically have the lowest recidivism rates of most returning citizens. If the youthful offender parole bill applied to them, the years they have already served might allow them to already be going home. Similarly, if they had been convicted pre-TIS they would be home now as well. But since George Gomez and so many others were convicted between 1998 and June 1, 2019 they are stuck, set aside as a different species in purgatory, never to be released.

Illinois legislators have essentially said that yes, they believe that Illinois youth up to age twenty-one, coming from less stable environments, having certain mitigating factors, are less culpable and deserve a chance at life other than behind these walls. Yet, they stopped short in saying this is so only if they are sentenced after June 1, 2019. Apparently, neither the science, the evolving standards of society, or even the other states that have since changed their laws don’t influence Illinois lawmakers.

To add insult to injury, another new “criminal reform” bill, HB 3653, was recently passed. This has established yet another way for those sentenced pre-TIS to receive time off of their sentence for other programs. Now, this is good for them, and it also gives them the first crack at these programs. But it is another example of pathways that continue to be opened for others and yet remain closed to George Gomez, myself, and so many others.

So in the end, what can be done? Well, for starters we need real justice reform that affects everyone equally. The kind where politicians aren’t afraid of fear-mongering and political games played by their opponents. The kind that makes actual sense, and affects real change. The law can simply be made retroactive; this would be the most logical solution.

However the bill, as it stands, needs work. It does nothing to address the needs of the people who were incarcerated at such a young age. That could be accomplished by setting goals for them to reach when they see the parole board, as well as having the board restructured, since Illinois hasn’t really had a parole board in over thirty years. Essentially, this is a whole new process for Illinois and to truly meet the task there needs to be real change.

How we treat our youth speaks volumes about our society. The school-to-prison pipeline is all too alive and well in the state of Illinois. But, now, we have a real chance to change that and release some of the former youth like George Gomez and myself who are caught in its grip. Will we? We have the power to.

Phillip Hartsfield is a social activist who earned his bachelor’s degree in the history of justice with a sociological and psychological perspective, and is currently earning his masters degree in criminal justice. This is his first article for the Weekly.