On the evening of October 9, 2014, Darnell Smith stepped out of his grandmother’s home in West Englewood to wait for a food delivery that he had ordered for her. After a few minutes, the delivery car appeared and the driver got out of the car. Suddenly, another unmarked car pulled up alongside the curb. A man jumped out of the second car, lunged at Smith, and—without saying a word—immediately began rummaging through his pockets. Whatever the man found, he threw onto the grass beside them, as Smith struggled to break free from his grip. The delivery driver who witnessed the entire incident believed that Smith was getting robbed. But the man searching Smith’s pockets was a plainclothes police officer. “He just walked up and started doing it,” Smith recalls. “He said it was a narcotics investigation.”

Smith, who is thirty-eight and African-American, is one of over forty plaintiffs involved in a class-action lawsuit against the city of Chicago alleging that the police department’s indiscriminate use of stop and frisk—a search and seizure method which has made national headlines due to alleged discrimination by the New York City Police Department—is excessive, often racially motivated, and a violation of civil liberties.

“The majority of the people you see stopped by both the white and the black police are black,” says Smith, speaking about the racism he sees as inherent in such police practices. “To the best of my belief that’s the only reason [for the stops].”

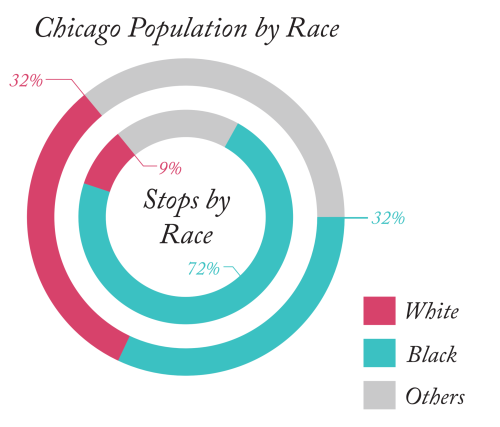

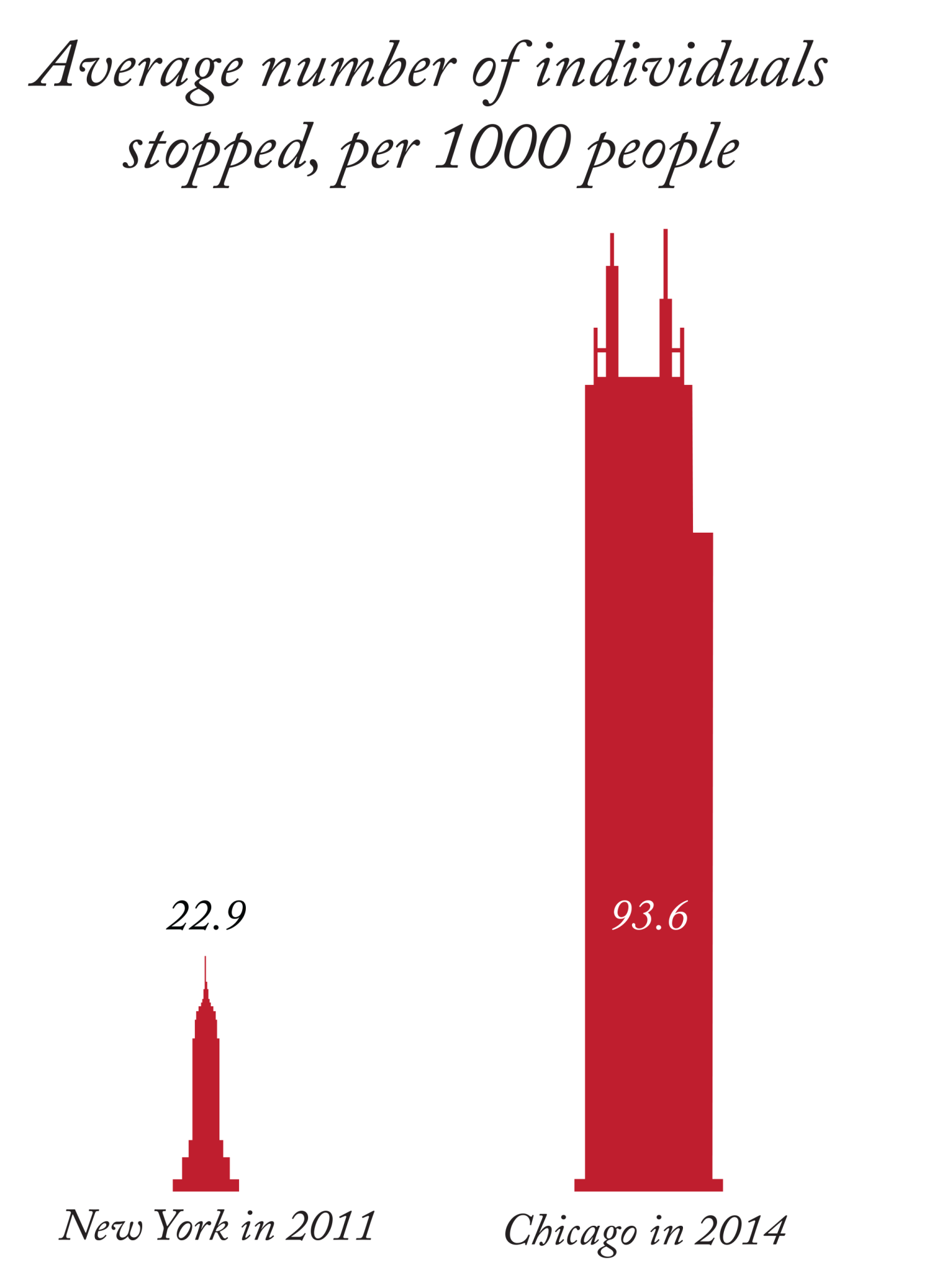

Smith’s assertions are backed up by research from the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Illinois, which released a report in March highlighting the depth of the racial disparity in stops in Chicago. The report shows that even though black Chicagoans make up only thirty-two percent of the population, they account for seventy-two percent of stops, while the city’s white population—which makes up the same thirty-two percent of the city’s total population—accounts for only nine percent of stops. This disproportionality is highlighted in neighborhoods like the Near North Side, where black people make up 9.1 percent of the population but a stunning 57.7 percent of stops. Additionally, the sheer volume of stops in Chicago dwarfs that of New York City even at the peak of New York’s stop and frisk program in 2011, when police averaged 22.9 non-arrest stops per 1000 people. In Chicago, this number was four times higher in the summer of 2014—93.6 individuals per 1000 people, or nearly ten percent of the entire municipal population, were stopped.

Because of the lack of consistent and reliable data-keeping on the Chicago Police Department’s part, these statistics have only recently become available to the public. Even though the scale of the problem evidently eclipses stop and frisk in New York by a wide margin, the relative lack of institutional reform has left communities of color in Chicago frustrated and desperately searching for avenues for change.

Stop and frisk has been practiced by police departments across the country since the late 1960s, bolstered by the Supreme Court decision in Terry v. Ohio. In the majority opinion of the 1968 case, stops and frisks—or Terry frisks, as they came to be called—were justified under the Fourth Amendment as long as a police officer had reasonable suspicion that an individual was a danger to officers or to the public. Legally speaking, a frisk constitutes a pat-down of someone’s person, and thus is short of a search and seizure. A Terry frisk therefore does not require the probable cause an arrest does, and as long as a police officer is “reasonably suspicious” that an individual might be a danger to the public, they are justified in their stop.

In the last few decades, Terry stops have gained popularity as a policy aimed at reducing gang activity and gun violence and have been used by police departments across the country, including the CPD. But since many incidents of stop and frisk do not result in an arrest, it is difficult for courts to evaluate the “reasonableness” of police behavior, and thus officers are rarely held accountable for breaches of the law. The contact cards officers fill out are also insufficient. Since officers are not required to fill these out if the stop leads to an arrest, exact estimates of Terry stops are hard to pin down. This also means that it is difficult to determine how often these stops lead to an arrest, making a thorough investigation into the efficacy of the policy nearly impossible.

However, looking at long-term trends, there is no clear indication that the broad use of stop and frisk is correlated with drops in crime and violence. For instance, according to the New York Civil Liberties Union, the number of people who fell victim to shootings in 2011 was roughly the same as in 2002. Additionally, as reported by the New York Times and other outlets, violent crime fell in 2014, even as the number of stops in the city fell sharply. While this drop may have been due to increased funding for the NYPD and the subsequent increase in police officers, these numbers call into question claims often made by “tough on crime” advocates that ending stop and frisk would necessarily drive crime numbers up.

Even researchers who have found potentially positive effects stemming from the policy are cautious about recommending its use. Jens Ludwig, the director of the University of Chicago’s Crime Lab, and Carnegie Mellon University’s Jacqueline Cohen conducted a 2003 study in Pittsburgh that found that stop and frisk led to decreases in gunshot injuries. But Ludwig is wary of extrapolating the policy’s overall value from such results. “That’s not to say whether or not stop and frisk is worth the costs that the practice imposes on society,” he says. “But there’s a complicated trade-off here that needs to be acknowledged.”

The trade-off Ludwig is referring to is the impact the practice has on urban populations, especially communities of color. The ACLU report points out that stop and frisk has consistently been shown to be damaging to police-community relations, because it breaks down the trust between the two groups that is vital for police work to be effective. Antonio Romanucci of Romanucci & Blandin, LLC, the law firm representing Darnell Smith in his lawsuit, agrees. “When there’s no trust, people run away,” he says.

Following the release of the ACLU’s report in March, calls for reform have focused mainly on improving the methods of collecting data on individual stops. The Chicago-based racial justice organization We Charge Genocide (WCG) began working with several aldermen on a comprehensive city ordinance that would shed light on the CPD’s practices by exposing them to public scrutiny. WCG, which entered the international spotlight after traveling to Geneva to bring institutional racism in the United States to the attention of the United Nations, drafted the Stops Transparency Oversight Protection Act (the STOP Act) with Aldermen Joe Proco Moreno and Roderick Sawyer this summer. Specifically, the STOP Act would mandate data collection on all stops, the release of this data to the public, and the mandatory issuance of receipts to individuals stopped by police, mirroring policies currently in place in New York City, where the data from each individual stop is readily available at the Stop, Question, and Frisk Report Database on the city government’s website.

However, the STOP Act was never filed—according to We Charge Genocide, Aldermen Moreno and Sawyer were dissuaded from filing the act until the September City Council Meeting by Mayor Rahm Emanuel, who claimed that the city was reevaluating its policing policies. This reevaluation consisted of secret negotiations between the CPD and the ACLU, which had been working with and had encouraged WCG to draft the STOP Act. On August 7, the fruits of the negotiations emerged from behind closed doors, and the ACLU unveiled a “landmark agreement” it had struck with the CPD on stop and frisk in the city. The details of the agreement mirrored the STOP Act in many ways, including a data collection requirement for all stops. The agreement also included changes in police training and supervision.

But unlike the STOP Act, the agreement mandated that the collected data would only be available to a third party investigation led by former federal judge Arlander Keys and a team of specialists, who would release two annual reports on their findings. Unlike in New York City, the raw data would be unavailable to the general public, although when asked about this point, Karen Sheley, Staff Counsel for the ACLU of Illinois, responded by saying that journalists can pursue the data through Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests. Making a FOIA request can be a difficult process, however, and it takes most requests nearly a month or more to be processed.

In an open letter to the ACLU of Illinois, We Charge Genocide derided the ACLU’s decision to exclude them from the negotiations, claiming that the move was detrimental to their efforts to curb police racism. “We informed you [the ACLU of Illinois] on July 1, 2015 that WCG would send out a press release and file the STOP Act on Wednesday, July 29 at the City Council meeting,” the letter says. “It was mind-boggling to learn that you have been in negotiations with the City without informing us prior to July 29.”

“We invited We Charge Genocide to participate in our litigation efforts and they said no,” says Sheley. “If they agreed and said they wanted to do that, they would have been part of that communication stream.” Sheley also says the STOP Act could still pass. “We weren’t informed of the date when they were planning to file it, but we still think it’s a good idea. I think that the timing of it made it difficult to go forward at that particular time.”

Whatever the cause of the communications breakdown between WCG and the ACLU, the result was a deal crafted within the establishment, in a process that did not include grassroots organizations aimed specifically at advocating for those most affected by the policies in question: black and brown people in Chicago.

Although Sheley stated that the ACLU has been and will continue to be open to additional efforts to expand data collection and the public’s access to it, such a public disclosure of data is only the first step in dismantling what many see to be a policy that has overstepped the legal framework set up by Terry v. Ohio. Although publicly accessible data on stops and frisks helped bring the scope of the problem to the attention of New Yorkers, it took a legal precedent for the NYPD to begin drawing down the use of the practice. Floyd v. City of New York, a case decided in 2013, made it clear that stop and frisk as it had been practiced in New York City violated the Fourth Amendment, since the frisks were deemed to be largely “unreasonable.” The court also ruled that, since many of the stops had been found to be racially motivated, the Fourteenth Amendment had been violated too. In conjunction with the decision, the court ordered a series of remedies, including broad reforms to the training and monitoring of officers. According to the New York Civil Liberties Union, stops have fallen dramatically since the NYPD complied with the order, from the 2011 high of more than 680,000 to only a little over 46,000 stops in 2014.

For this reason, Romanucci, Smith, and the other litigants believe that a legislative solution can only do so much, and thus intend to use the court system to change policy. Despite the steps toward reform that the ACLU-CPD agreement provides, it provides no immediate relief on the ground, as CPD Superintendent Garry McCarthy himself pointed out following the announcement of the deal. Because the data collection won’t go into effect until January, because processing and analyzing the data will take longer, and because the prospects of broader reforms are uncertain, the agreement does nothing in the short-term to impact the lives of people of color targeted by police officers.

Darnell Smith says he has been stopped twice since the initial incident in 2014. “It’s not like you get stopped and frisked once and then you get a special card that says you will never get stopped and frisked again,” Romanucci says. “You will continually get stopped and frisked solely because of race.” Smith also says he fears “retaliation” on the part of the police for what he is doing, saying that he could get handed a narcotics charge if he makes the wrong move. “A lot of people don’t have the heart to do this because of the fear that the police have instilled in them,” he says.

But Smith remains confident about the potential for reform. “With the court’s help,” he says, lasting reforms to the CPD’s stops and public access to their data are both possible and close to becoming reality.

true that