The artwork at Pilsen’s Uri-Eichen Gallery won’t approach you with a clipboard. It seeks no signatures—just time. And maybe a little bit of action.

This week, Uri-Eichen launches a five-month series on income inequality, featuring an array of artists—from photographers to cartoonists—whose work speaks volumes on the effects of wage disparity. The series opens just as the budget stalemate in Springfield approaches the one-year mark, making Illinois the last and only state in the nation still without a tax and spending plan for the 2015 fiscal year, which began in July. Potential progress has been reported in recent weeks and a so-called “grand bargain” may yet be in the works between Gov. Bruce Rauner and General Assembly Democrats. But meanwhile, the backlog of unpaid bills facing the state is rolling quickly toward the $10 billion mark.

In 2011, Kathy Steichen opened the Uri-Eichen Gallery with her husband, Christopher Urias, combining their surnames to form the gallery’s name. Steichen, who hails from Iowa, has been involved in activism surrounding issues such as labor rights and racial justice for more than 25 years. Urias, a native of Pilsen, and Steichen are both graduates of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Shortly after Gov. Rauner’s election victory in November 2014, he revealed a policy plan that focused heavily on reducing the influence of organized labor across the state and particularly in Chicago. This focus has materialized in a forced weakening of collective bargaining rights, as well as the recent elimination of overtime compensation for home healthcare caregivers, to name just a few consequences. Steichen, who has worked in the labor movement for over seventeen years, sees a challenge in helping people understand and voice their concern with the state’s direction.

“There’s a goal of every show [at Uri-Eichen] having a component of activism attached to it,” Steichen says. Exhibitions at Uri-Eichen, which have focused around issues including reparations for slavery and the Chicago Teachers Union strike, are commonly curated to raise awareness of pressing issues and inspire visitors to take action. On tables and on windowsills in the gallery, patrons can find materials related to programs supporting teachers unions, racial justice groups, and more. The gallery also frequently brings in activists and community leaders as speakers to inform others as to how they can join a movement or influence legislation.

The genesis of the gallery’s current series on income inequality had several components, Steichen says. The first was the Supreme Court’s 2010 decision on the Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission case, which allowed corporations and unions to spend unlimited amounts of money on political activities independent of a party or candidate. The ruling has had a drastic effect on the business of U.S. politics in the years since, especially in Illinois. In conjunction with the campaign finance law, the decision has led to unprecedented spending, especially evidenced in the most recent gubernatorial election of 2014. About half of the $65 million invested in the campaign came from Gov. Rauner’s private funds and the funds of nine other individuals, families, or corporations they control.

Steichen was then led to consider the fact that the top twenty percent of households in the U.S. possess more than eighty-four percent of the nation’s wealth, while the bottom forty percent of households account for a mere 0.3 percent. The fight for a minimum wage raise to match current costs of living—now known as the Fight for 15 movement—was another motivating factor that convinced the gallery’s board of directors to forge ahead with the nearly half-year program, she says.

The first exhibition in the series, A New American Portrait, is a collection of screen-printed pieces by Los Angeles-based artist Oscar Magallanes that juxtaposes the icons of various social movements with pop culture imagery and phrases to construct messages on critical issues including labor rights, slavery, Native American history, and terrorism, among others. Drawing on Diego Rivera and Bertram David Wolfe’s Portrait of America collaboration, in which students of the New Workers School in New York were asked to create alternate histories of the United States, Magallanes has engraved a range of dates at the top of each piece, which read almost like tombstones. While each piece could stand alone, Magallanes’ work maintains consistency by using the same bold colors throughout: orange, red and blue.

One piece shows an outline of a man carrying a knapsack that appears connected to a huge ball of cotton. In the background are, in all capitals, the words “FREE LABOR.” To the left, a noose hangs over a vertically written message: the name “John Punch,” a man considered one of the first official slaves in the British colonies during the seventeenth century. At the top of the piece, the stripes of the British Union Jack reach out toward the noose; a traditional crown sits at the center. Overhead are the years 1492, the year of Christopher Columbus’ arrival to the Americas, and 1640, which marked the end of the Iberian slave trade.

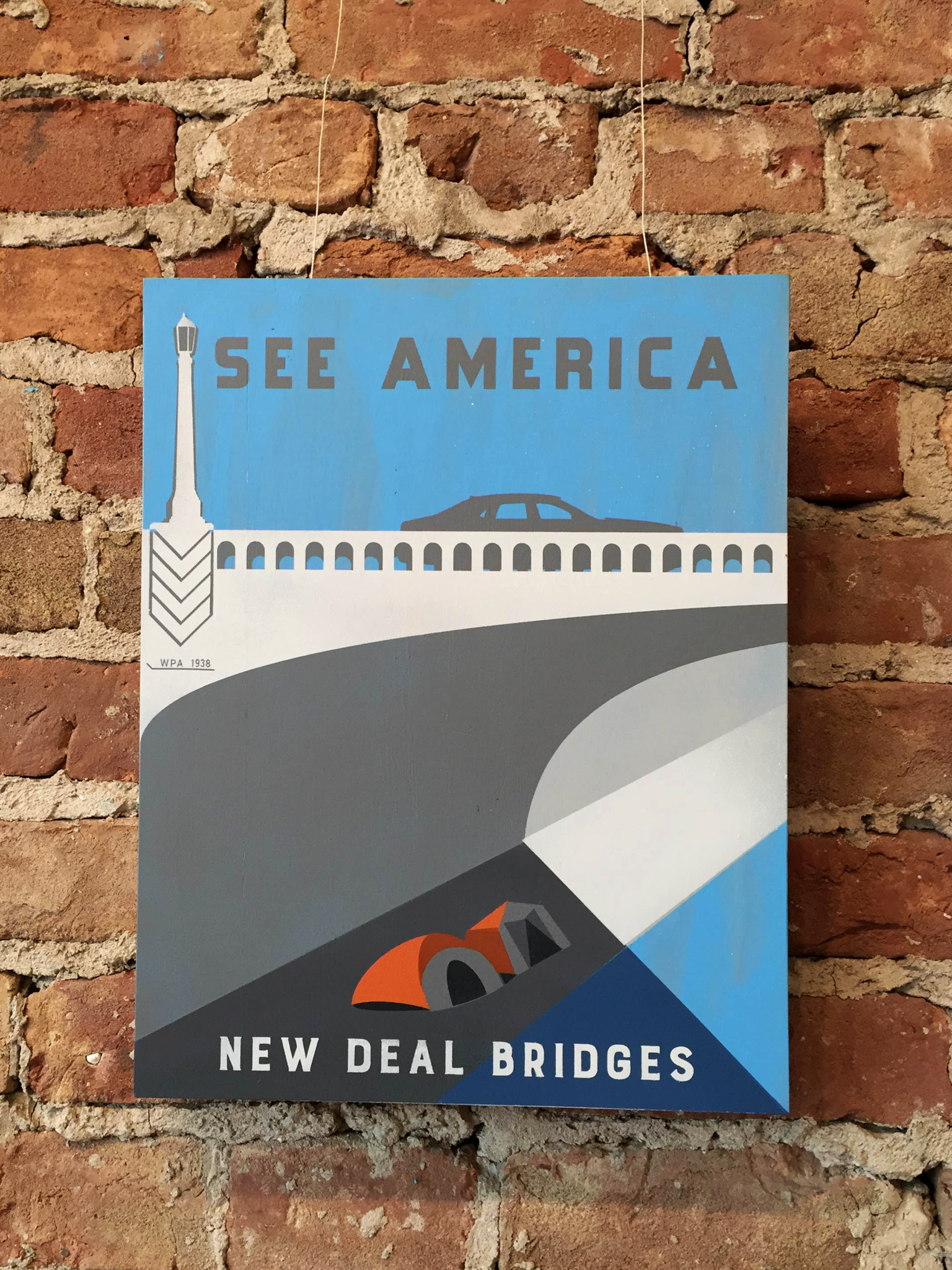

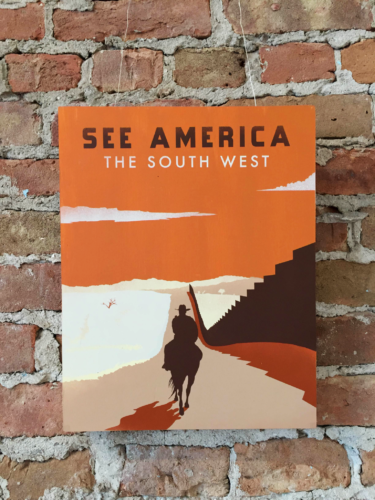

A separate, four-part collection of screen-printed pieces by Magallanes also on display at the gallery combines timeless, all-American motifs with iconography that denotes current social justice issues. The words “See America” border the top of each piece. In one, a man at first appears to be taking in a desert landscape on horseback; the border wall to the right, however, suggests another identity. In another, a car rides over a New Deal Bridge that towers above two tents pitched in its shadow.

More than just the art on display builds community and encourages activism at the Uri-Eichen Gallery. The main space of the gallery, which stands at the corner of Halsted at 21st Place, is about the size of a large living room. Steichen says the cozy atmosphere fosters intimate and constructive dialogue among patrons. “It’s the perfect venue to start a conversation,” she says.

Elsewhere, in Chicago and beyond, that level of conversation is sorely lacking, Steichen believes. As a consequence of the eight-hour workday and other major societal shifts, “people don’t belong to bowling leagues or engage socially in community settings as much as they used to,” she says. “The biggest challenge is getting people involved. We still have the ability to vote, to get engaged and change things.”

Starting Friday, May 13, the public will have an opportunity to view Magallanes’ artwork and learn more about the series on income inequality. To kick off the five-month series, the gallery hosted William McNary, co-director of Citizen Action/Illinois, a progressive political coalition for social justice and the state’s largest public interest group, who spoke on the topic on the series’ opening night.

On Saturday, May 14, the gallery then hosted a reception and photography display, featuring images that celebrate the life of Les Orear, a stockyard-worker-turned-community-organizer. That same day, Illinois Labor History Society dedicated a bench at the historic Union Stockyard Gate in Orear’s memory.

Throughout the summer months, until September, the series will introduce a new show focused on income inequality in America each month. In June, Uri-Eichen will feature a collection called Maxwell Street’s Last Hope, a result of a collaboration between the gallery and the Maxwell Street Foundation. Drawing on the oral histories of the historic market’s past vendors, captured by multimedia artist Nicholas Jackson, and featuring the photography of Ron Gordon and Lee Landry, the exhibition will tell the story of the market’s downfall in the 1990s after nearly a century of economic perseverance and cultural significance.

July will see the arrival of a photography exhibit 1%: Privilege in a Time of Global Inequality, featuring artists from across the globe whose work highlights wage disparity as it pertains to travel, entertainment, and health care. In one photograph by Guillaume Herbaut, a bride in China poses for her wedding photos on a plush red sofa while two men hold portable lights over her head. In another, by Guillaume Bonn, a chef stands beside a table set in the middle of a grassy Kenyan field, where he waits to serve champagne to guests on a hot air balloon excursion. The exhibit, now at Roosevelt University’s Gage Gallery, has traveled all over the world.

To cap off the series, the work of cartoonists Gary Huck and Mike Konopacki, whose work centers on issues around labor and social justice, will be featured in August.

According to Steichen, art is a perfect gateway to activism, making Uri-Eichen’s marriage of the two a no-brainer. “Artists are able to encapsulate a lot of ideas in one construction and they get you to think about those ideas in a way that normal interactions in our society—watching television news or reading a newspaper article—may not,” Steichen says.