- Best Self-Guided Aviation Tour

- Best “Friend” of the Lithuanian Diaspora

- Best Secret History of a Mall

- Best Grilled Cactus

In Chicago’s early history, the Midway area was largely undeveloped. The Orange Line didn’t extend from downtown to the airport until the 1990s. The area first grew slowly around transportation, manufacturing, and shipping. Later it was blanketed with single family home subdivisions during mid-century. Near the northwest tip of Garfield Ridge, Mud Lake once connected the North Atlantic and the Gulf of Mexico, by linking Lake Michigan with the Mississippi River, before it was drained for industrial sites. The Chicago Portage National Historic Site nearby preserves a link between Chicago River to the Des Plaines River.

From World War I until the 1960s, the aviation industry transformed the southwest area of Chicago, which was the location of two of the most important aviation hubs in the United States, Ashburn Flying Field and Chicago Municipal Airport—later renamed after the Battle of Midway. While the Ashburn airport later closed, Chicago Midway International Airport (MDW) continues to operate as a hub for Southwest Airlines.

In West Elsdon, a mostly Hispanic population lives an American Dream many of us have forgotten—neighbors greeting each other, groups of children riding bikes, and family gatherings in backyards.

Eastern European immigrants continue to live in Garfield Ridge, where you can find impressive bakeries—I debated between buying Lithuanian rye bread or Polish and sampled delicious fresh buns with centers stuffed with cheese, bacon, or chicken.

In West Lawn and Clearing, there are plenty of Blue Lives Matter signs supporting police officers, among the ubiquitous Proud Union Home yard signs. Since city employees are required to live within the city limits, plenty of residents move here because it’s affordable and feels like the suburbs.

In the postwar years, racial tensions flared when Black veterans tried to move into CHA’s veteran Airport Homes after World War II. Black veterans who occupied apartments in protest of their treatment were labeled as “squatters” by the press. While the harassment at some marches for integration, like one in the Bogan High School district, remained minimal, the rioting by white neighbors in West Elsdon and West Lawn lasted over a couple years, and racial strife would continue through government desegregation attempts and school busing orders.

What I’ve seen most in the Midway area are hardworking residents who receive little recognition. The Southwest Side doesn’t attract tour buses. The area’s greatest industrial achievement, the Dodge Chicago factory, manufactured military aircraft engines on a scale the world had never seen before. It’s an accomplishment that should be a proud legacy, yet in historical accounts of Chicago, is all but ignored.

Samantha Clark is a freelance writer and photographer. As part of her Chicago Neighborhoods Project, she visits, researches, and documents each of the city’s seventy-seven community areas.

Best Self-Guided Aviation Tour

1. Ashburn Flying Field

8333 S. Cicero Ave., now Scottsdale Park subdivision

Chicago’s first airport, opened in 1916. After World War I, it was a center of national aviation, as well as being utilized for U.S. Post Office airmail, and was in use until World War II.

2. First Passenger Airline Flight

Ashburn Field to New York

Chicago saw the beginning of passenger airline service (or, as the Tribune termed it, the flight of a “gigantic aerial train”). It was a bumpy start. The plane almost crashed during refueling stop—and it was cold.

3. Largest Factory in the World During WWII

Dodge Chicago Plant, now Ford City Mall & Chicago Industrial District

See Best Industrial Ruin.

4. Worst Ground Airplane Disaster

Near 63rd Pl. and Kilpatrick Ave.

According to the 1959 Tribune, “a heavy Trans World Airlines freight plane fell like a flaming bomb into an area of small homes and apartments just southeast of Midway field,” causing eleven deaths and eleven injuries.

5. World’s Busiest Airport in the 1950s

5700 S. Cicero Ave., now Chicago Midway International Airport (MDW)

Originally named Chicago Air Park, it was renamed Chicago Municipal Airport in 1927 and then the Chicago Midway Airport we know and love in 1949.

6. Chrysler Village Planned Worker Housing for Dodge Chicago, WWII

South of Midway airport, centered on Lawler Park, 5210 W. 64th St.

Chrysler Village, and other World War II worker housing projects like it, helped define modern suburbia.

7. Airplane Rentals & Fueling

S. Laramie Ave., north of 63rd St.

Ever wonder where private airplanes go to refuel? Find Aviation concierge services here, including heated hanger parking and public flight lessons.

8. Row Houses for War Workers, WWII

East side of Long Ave., between 63rd St. and 65th St.

More housing planned for Dodge Chicago workers during World War II. Rent was expected to be forty dollars.

9. Midway Armory

5400 W. 63rd St.

The Illinois Army National Guard’s two aviation companies and three detachments of aviation regiment medical evacuation are housed here.

10. Chicago Department of Aviation – Central Field Office

5642 S. Central Ave.

This city department administers all aspects of both Chicago airports—yes, even aircraft noise complaints.

11. Paparazzi Stake Out

East side of S. Central Ave., 58th St. to 60th St.

Private airplane flights for the well-to-do. Hang around for hours and you just might spot someone famous.

12. WWII Studebaker Engine Plant

Archer Ave. and Cicero Ave., now a business center

This factory for military aircraft engines later became a 1.5 million-square-foot distribution center for Sears, Roebuck & Co.

13. Chicago Transit Authority – Midway Yard

5601 S. Kilpatrick Ave.

The “L” wasn’t extended to Midway until the Orange Line opened in 1993, at a cost of $500 million. Around ten years ago the CTA began exploring expansion to 76th Street near Ford City.

14. Airport Homes CHA Housing Riots

61st St. and Keeler Ave., 1947 and 1948

White residents opposed integration of the CHA’s Airport Homes, designed for World War II veterans. The Tribune in 1976: “It was a terrifying experience for all.”

(Samantha Clark)

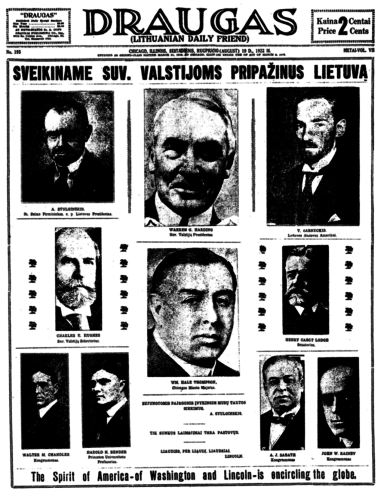

Best “Friend” of the Lithuanian Diaspora

Lithuanian Catholic Press Society

“Can you smell the ink?” asked Audroné Kizys, Draugas’s subscription manager. Kizys, Draugas News editor Vida Kuprytė, and I are walking over wooden cobblestones on the ground floor of the Lithuanian Catholic Press Society. Until recently, Draugas printed its daily paper in this back room. “I’m told that [the cobblestones] were here because of the printing press,” Kizys said. “They absorbed the static.”

The Lithuanian Catholic paper for which Kuprytė and Kizys work is the oldest continuously published Lithuanian paper in the world. First published in 1909 in Pennsylvania, it relocated in 1913 to the South Side, where the Lithuanian population numbered 50,000. The daily would play a central role in Lithuanian politics and culture. During Soviet occupation, Draugas would reprint dissident writings smuggled out of Lithuania, often in ingenious fashion—editor Jonas Kuprys recounted receiving sheets of paper wound around a roll of mints—and Draugas would be snuck back into Lithuania, maintaining a line of communication between continents.

The paper’s offices have drifted around the South Side, following the shifting Lithuanian neighborhoods: according to the paper’s collective memory and archival photos, Draugas editors worked on Rockwell Avenue, in Bridgeport, and in the Heart of Chicago before they settled into the paper’s current building on 63rd Street and Kolmar Avenue in 1955.

“It’s not as impressive as it used to be,” Kuprytė said with a half-smile, gesturing toward the space where the wet press used to sit. “The press was huge, now there’s just the stench [of ink].”

Draugas now publishes three times weekly and maintains an economical staff of seven, a gradual downsizing dictated by changing demographics: a slowing rate of immigration to North America and the assimilation of earlier waves. But under Kuprytė and Kizys, Draugas has grown in new directions. Since 2013, they have published a monthly English-language paper, Draugas News, and since 2014 a bi-monthly cultural magazine called Lithuanian Heritage.

Draugas now publishes three times weekly and maintains an economical staff of seven, a gradual downsizing dictated by changing demographics: a slowing rate of immigration to North America and the assimilation of earlier waves. But under Kuprytė and Kizys, Draugas has grown in new directions. Since 2013, they have published a monthly English-language paper, Draugas News, and since 2014 a bi-monthly cultural magazine called Lithuanian Heritage.

Though Chicago is no longer the epicenter of the Lithuanian diaspora (the Chicago suburb Lemont now claims the mantle—at least within the Midwest), the editorial staff is proud of their South Side roots. Kuprytė and Kizys are “Marquette kids,” and Kizys poked fun at Kuprys for being the lone “Cicero kid” in the room. As we walked by tables of books for sale in the lobby downstairs, the Marquette kids recommended several cookbooks—and a memoir entitled Growing Up Lithuanian in Marquette Park.

But the more things change, the more they stay the same. Draugas, which in Lithuanian means “friend,” promises its readers a selection of uplifting writings. The August edition of Draugas News contains a preview of a Lithuanian pianist’s performance in Rockford, an interview with interns at Chicago’s Lithuanian Center for Research, and articles about Lithuanian gatherings in Dayton and Canada.

“It’s a very nice publication,” Kuprytė said. “The Consul General was visiting once and asked, ‘What about this paper is so different from publications in Lithuania?’ And he read the whole paper from front to back, and he said, ‘It’s just so positive, everything is so positive.’” (Emeline Posner)

Lithuanian Catholic Press Society, 4545 W. 63rd St. (773) 585-9500. draugas.org

Dodge Chicago Plant

While most people are familiar with Pullman, the famous industrial company town, Chicago also once boasted the largest industrial manufacturing plant in the world, near Midway airport. During World War II the Dodge Chicago Aircraft Engine Plant occupied more floor space than the Merchandise Mart. Completed in twenty-one months, it was a marvel of industrial planning and engineering. Workers attended one of the largest mass training programs in history.

War factories in the area were designed so that they could be occupied by automobile manufacturers once peace returned. Chicago, planning to utilize government-built industrial resources, was positioning itself as the future center of the auto industry. Ford set its sights on Dodge Chicago, declining to purchase the smaller Willow Run plant they operated in Michigan during the war. (Their rival General Motors got Willow Run.)

At the end of the war, government housing authorities stepped in and announced the housing shortage was a greater need than producing automobiles; they chose Chicago prefabricated metal house manufacturer Lustron Homes to occupy the Dodge Chicago site. Meanwhile, the War Assets Administration (WAA) was taking separate bids, including from auto start-up Preston Tucker.

In May 1946 the Tribune reported, “If bids are unsatisfactory to WAA officials it is understood that the government will remodel the plant into small units and lease them to a large number of industries. All would be served by the Dodge-Chicago central power plant. Such a step by the government would relieve the present scarcity of medium and small sized industrial plants in the Chicago metropolitan area.”

Dodge Chicago was not connected to city utilities. Even turning on the lights meant activating the central power plant. Had either Ford taken over or the government created a small and medium manufacturing incubator, the history of Chicago industry would now be different. Instead, while government agencies bickered, Tucker used the excuse of counting leftover machinery to occupy the site. “Tucker expects eventually to produce 1,500 of his aluminum bodied engine-aft Torpedo cars every day,” the Tribune reported a couple months later. “At that rate the plant would turn out more automobiles in three weeks than it did aircraft engines in the entire war.”

Eventually Tucker prevailed in Washington, and was awarded the entire facility. He created auto prototypes in his Michigan workshop but never commenced production in Chicago. Lustron left the state and manufactured a disappointingly small number of homes. Both companies were bankrupt by the 1950s. Ford finally occupied the plant to make airplane engines during the Korean conflict. Afterwards, it was decommissioned. The factory was never successfully converted to civilian use. The site now houses the Ford City Mall and the Tootsie Roll Industries headquarters. (Samantha Clark)

432 acres bounded by Chicago Belt railroad, 79th St., Pulaski Rd., and Cicero Ave.

El Solazo

The gorditas nopales at El Solazo are exceptional: cactus, smoky from the grill, and soft roasted peppers stuffed into a delectable pastry shell. But the culinary exploration doesn’t stop there. Come at dinnertime for a vast selection of tacos for every taste, from tongue to tripe to pulpo a la plancha—grilled octopus, which you certainly can’t find at just any taqueria. Get a side of spicy pickled carrots to perk up your taste buds before diving in. If you’re feeling particularly carnivorous, try the parrilladas—a huge pile of meats, including spicy chorizo and sweet, buttery langostinos. The place is generally packed (a testament to its goodness). Skip out on the crowd by getting your food to go. (Amelia Soth)

El Solazo, 5600 S. Pulaski Rd. Sunday–Thursday, 9:30am–12am; Friday, 9:30am–3am; Saturday, 9:30am–4am. (773) 627-5047. elsolazochicago.com

Support community journalism by donating to South Side Weekly