Gun violence is a major problem in Chicago, increasing the need for violence prevention. This year alone we have already experienced 716 homicides, which is a fifty percent increase over the total homicides last year. Like COVID-19, gun violence is a pandemic and has to be treated from a public health perspective: as a disease that, if left untreated, will spread like any other disease. I have been doing violence prevention work now for ten years. Recently, while reading an article, I found a striking fact: despite fluctuations in the murder rate over the years, Chicago has averaged a little over 500 murders a year for the last twenty years. However, there is something unique about the increase in homicides in 2020. How did we manage a fifty percent increase in homicides while under quarantine and stay-at-home orders due to COVID-19? Although there may be many reasons for this increase, I would like to point to three issues: the failure to treat gun violence as a public health issue, the disenfranchisement of poor Black and brown youth, and lack of accountability from the Chicago Police Department.

Both the Center for Disease Control and the World Health Organization have adopted the United Nations findings recognizing the fact that gun violence is a public health problem, and has to be treated from a public health perspective. The public health approach addresses the fact that violence is a learned behavior and if not interrupted will be transmitted and spread like any other disease that goes untreated.

Most of those that chose to commit violent acts have learned this behavior and accept violence as a normal solution to their daily problems. In their minds, they are oppressed and violence is necessary. In Wretched of the Earth, Frantz Fanon argued that violence is necessary and natural against an oppressor like a colonizer. However, to the oppressed, the world is small and they only see people who look like them and see them as their oppressor.

Most of those that chose to commit violent acts have learned this behavior and accept violence as a normal solution to their daily problems. In their minds, they are oppressed and violence is necessary. In Wretched of the Earth, Frantz Fanon argued that violence is necessary and natural against an oppressor like a colonizer. However, to the oppressed, the world is small and they only see people who look like them and see them as their oppressor.

Black and Latinx people together make up nearly sixty percent of the population in Chicago. However, nearly eighty percent of gun homicides occur in poor Black and brown communities like Englewood, Austin, and Humboldt Park. This unacceptable disparity, and the fact that those in power refuse to accept gun violence as a public health problem, has led to many unsolved murders and the increase in the murder rate. The community resources needed to solve this problem have been woefully underfunded, mostly addressing the effects of the problem and not the root of the problem itself.

In Mike Royko’s Boss, a history of Richard J. Daley’s years as mayor of Chicago, the legendary newsman noted that Chicago is one of the most segregated cities in America. Boss told the story of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. coming to the city to protest racial discrimination and marching through one of Chicago’s predominately white neighborhoods. He was spat on and hit with bricks and treated like he was not even a human being. Dr. King stated that the racial oppression he experienced in Chicago was far worse than any racism he experienced in Southern states. Much of what Royko noted about Chicago neighborhoods in the 60s still exists today. Today, Chicago still remains a city divided along lines of race and income.

What does all this have to do with gun violence or COVID? As long as gun violence is perpetuated by and against the less fortunate, those in power will not treat gun violence as a public health issue. When something becomes a public health issue, it is seen as affecting whole communities and adequate resources are directed to solving the problem. As long as gun violence was contained in these poor Black and brown communities, it was not treated as an issue.

What does all this have to do with gun violence or COVID? As long as gun violence is perpetuated by and against the less fortunate, those in power will not treat gun violence as a public health issue. When something becomes a public health issue, it is seen as affecting whole communities and adequate resources are directed to solving the problem. As long as gun violence was contained in these poor Black and brown communities, it was not treated as an issue.

The pandemic changed all this, and exposed gun violence as a public health issue that needs to be addressed immediately. We were not ready for COVID; it has changed our lives forever. For the first time in my life, all major sports were shut down, schools closed, and we were ordered to stay at home. But COVID did something else: it overburdened the health care system. Hospitals were filled beyond capacity with COVID patients to the extent that many hospitals were unable to treat other patients.

Now, in addition to COVID, we have a fifty-percent increase in gunshot patients that have to be admitted to the hospital, further overburdening a system on the brink. Hospitals are experiencing a shortage of health care personnel, as workers now have to worry about their lives when victims of gun violence come in because many are suspected to be COVID-positive. The city was forced to deal with a monster that has been lurking in the shadows for the last twenty years—except now this monster is wreaking havoc on the whole city and not just poor neighborhoods. COVID-19 has exposed how gun violence affects the whole city and not just the population where it was predominately happening. It should be noted that COVID has disproportionately hit the Black community; Black Chicagoans make up almost forty percent of COVID-related deaths.

Most victims of gun violence are from poor Black and brown communities. In addition, the shooters are also poor Black and brown individuals. It would be illogical to conclude that this group is just more violent, especially without taking other structural factors into consideration. Violence is a learned behavior, and this group has long been disenfranchised and stereotyped as having violent tendencies.

Most victims of gun violence are from poor Black and brown communities. In addition, the shooters are also poor Black and brown individuals. It would be illogical to conclude that this group is just more violent, especially without taking other structural factors into consideration. Violence is a learned behavior, and this group has long been disenfranchised and stereotyped as having violent tendencies.

Victor Rios is a formerly incarcerated professor and author who conducted in-depth research into the lives of Black and brown young men in urban areas. He concluded that these young people strive for dignity in a social landscape that seems to deny them basic human acknowledgment. We can trace Chicago’s rich history of denying young Black and brown children basic human rights from the creation of the projects, to the Jon Burge torture era, to now where in some neighborhoods they have a police station literally posted up at schools to criminalize age appropriate behavior.

Conditions that poor Black and brown youth live under are a result of systemic racism. Then COVID comes along and forces those already living in overcrowded, under-resourced areas to stay at home and quarantine! This increased everyone’s tensions, and with everything basically closed, people hung in the neighborhood more and increased the violence.

Finally, I want to point out that gun violence increased during COVID because there is a lack of accountability when it comes to how law enforcement treats Black and brown boys. What does this have to do with COVID, one may ask? Earlier I mentioned how Black and brown youth are treated by the police. I talked about Jon Burge and police in the schools. Although George Floyd was not killed in Chicago, his death was recorded for the world to see as he screamed for his life. After Floyd’s death, major protests across the world ensued. Although the police murder of Black suspects had been an issue for some time, it was Floyd’s death that set a new and unprecedented tone. There was a sweeping demand by citizens for police reform and the demand to end systemic racism.

The call for police accountability put pressure on the Chicago police force and for some time this summer, it seemed poor Black and brown communities were practically unpoliced. At this time violence swept through these communities like wildfires. There were news reports where the police just watched looters loot the city. Chicago police also violently beat protestors with batons, tear gas, and more. As a result, the violence exploded as the police sat back and did little.

It is not my premise that COVID-19 alone caused the increase of gun violence in Chicago. COVID exposed preexisting conditions that have gone unaddressed for years, such as how violence is viewed, how Black and brown people are treated by the city at large, and the abuses of the Chicago Police Department. We must treat this issue as the public health crisis that it is by directing resources to address the root causes.

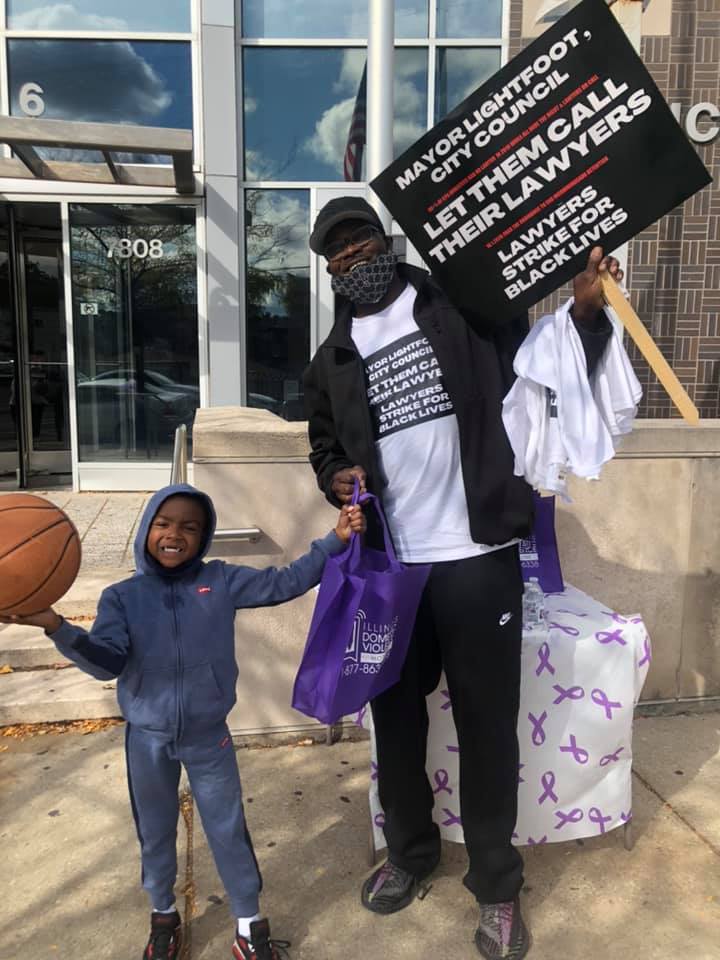

Charles Jones was born and raised in Englewood. He was a legal worker with First Defense Legal Aid, where he worked on police misconduct lawsuits and conducted know your rights workshops. In addition, Jones was a violence prevention/intervention specialist with Opposite Negative Environment. Jones was incarcerated for over a decade after being forced into a false confession by Chicago police after he was held incommunicado when he was a teen. After coming home, Jones dedicated his life to ending incommunicado detention, police violence, and intracommunal violence. Charles Jones passed away on November 27, and will be missed dearly by his family and the many people whose lives he impacted and transformed.

I would like to point to another reason for the 50% increase in homicides that you rather conveniently forget to highlight-far more relevant to the problem than lack of police accountability- that being POOR parenting. Let’s not try to fool ourselves. There are far too many feral teenagers roaming the south and west sides. Where are the parents? Don’t you ever ask yourself that question? Don’t start complaining about police accountability, and ignoring parental responsibility. You can improve police accountability until the cows come home, but until you look at improving the social fabric of the Black family, NOTHING will change. The author here seems to be taking his eye off the ball. Sounds like the author can”t see the forest thru the trees. Come on man-get in the game.

What happened to my comment about BAD parenting being a more important factor than police accountability ? Didn”t that comment fit the ‘victim’ narrative that this paper wants to push? Open your eyes people, it’s obvious. I thought you folks were all about diversity? How about diversity of ideas or doesn’t that work in your universe? This is just another left wing intolerant rag of a newspaper. Have a nice day.

Hi Doug — your initial comment was posted on Saturday evening. As a small, community-run independent paper, we don’t have people monitoring & approving the comments 24/7. It’s now been posted. Have nice day.

Hi Doug,

You’re a buffoon.