City officials were excited to approve plans for a new Amazon warehouse in Bridgeport in November 2020. Maurice Cox, Commissioner of the Department of Planning and Development, applauded Amazon’s development team for “watching out for the public interest” and “setting a new standard” for future logistics facilities.

Not everyone was celebrating, though. Ten community organizations, the Metropolitan Planning Council, and multiple residents spoke or signed on to letters opposing the development.

“Chicago is not for sale, it is not just a square to exist on Amazon’s Monopoly board,” wrote Phan Le, who identified as a “future Bridgeport resident” in her comment to the Plan Commission.

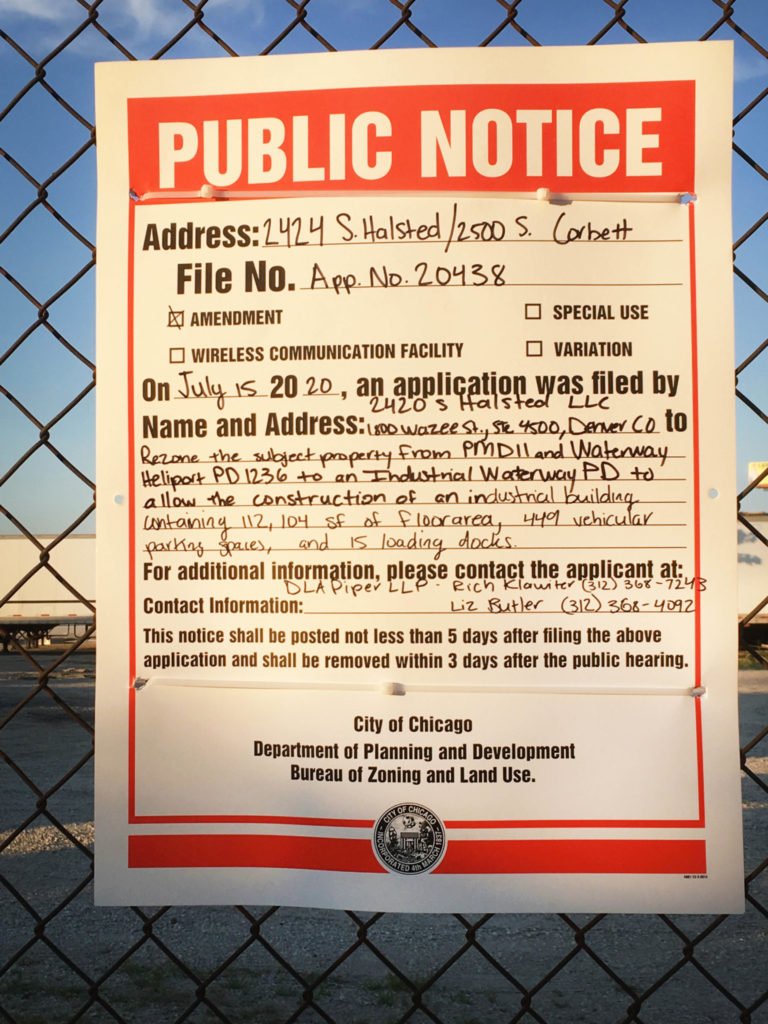

The development will combine two sites—2420 S. Halsted Street and 2500 S. Corbett Street—along the South Branch of the Chicago River. Prologis, the country’s largest developer of industrial real estate, will lease the building to Amazon.

The proposed 112,000-square-foot warehouse is part of Amazon’s latest push into the city with its “last-mile” facilities. These facilities are warehouses built closer to customers’ doorsteps that allow the e-commerce giant to compete with retailers for same- or next-day deliveries.

Amazon has been tight-lipped about their expansion in Chicago, but according to people familiar with the transactions, there will be seven last-mile facilities in total. Warehouses are already open in Pullman, the Near North Side, McKinley Park, Little Village, Gage Park, Cicero, and now slated to open in Bridgeport.

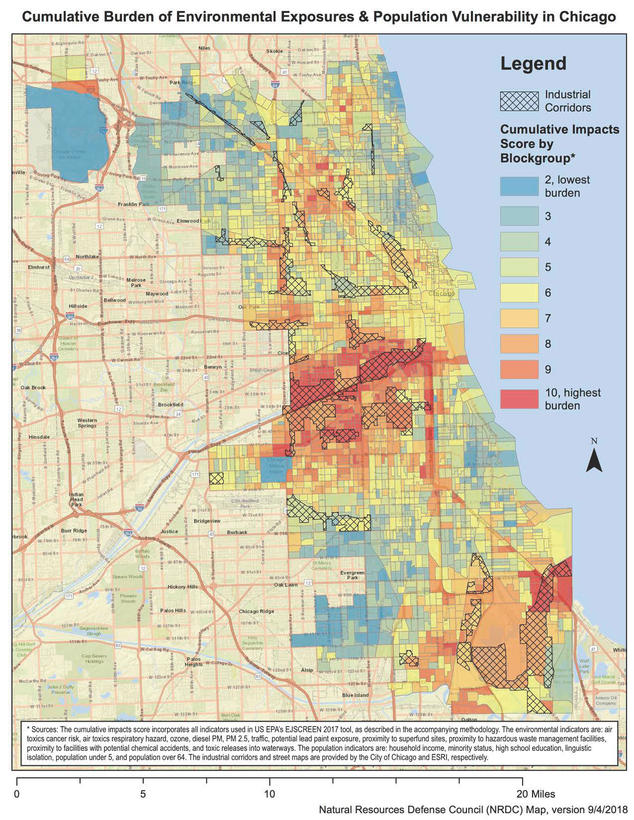

This means six of the seven facilities will be on the Chicago’s Southwest and Southeast sides, which comes as no surprise to activists who have long called out the city’s inequitable distribution of heavy industry and environmental harm.

In Bridgeport, the proposed Amazon warehouse will come at the expense of the residents who live there in the form of increased traffic risk, more pollution, and the loss of valuable riverfront land. Even amid strong opposition and growing scrutiny of Amazon’s taxpayer-funded expansion, the warehouse was approved because of the decisions the city, developers, and elected officials made behind closed doors with little input from the residents they’re supposed to represent.

Hundreds of trucks and delivery vehicles 24/7

In 2007, Raymond* and his family moved to a small residential neighborhood west of the proposed Amazon facility, referred to informally by residents as Bridgeport Landing. Drawn to its riverfront location, views of the city, and proximity to public transit, he initially didn’t think much of the large industrial lots a few steps away.

“In the beginning we saw those lots being vacated and cleaned, we were thinking it’s gotta be something residential,” he recalled.

He was wrong. First there was Chicago Helicopter Experience, a controversial heliport which flew helicopters day in and day out over his neighborhood for more than five years. It finally left last summer, according to residents. But before he could breathe a sigh of relief from the noise, Raymond received a letter about a new warehouse near his home.

“It’s just unbelievable that they would put a huge commercial site like Amazon there,” he said.

The warehouse will be in operation twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, so hundreds of vehicles will pass through at all hours, with the highest truck volume during the night and early mornings. On a peak day, more than 600 commercial vehicles, including forty-two semi-trucks and 421 delivery vans, will drive in and out of the facility, according to a traffic study prepared for Prologis.

For Raymond, the vehicles’ endless beeping will keep him and his family up on summer nights when they have their windows open for air. “There are other warehouses along the river, but they’re very quiet. Amazon is a different operation,” he said.

The residents of Bridgeport Landing also have safety concerns about the number of vehicles that will weave through their community to access and entrance on Senour St., a narrow residential street between the neighborhood and warehouse site where children often play. Traffic estimates indicate that during peak afternoon hours alone—from 4-5pm—there could be eighty vehicles entering and exiting through Senour. “I don’t want to see any of my neighbors get injured,” said James*, another longtime resident. More than twenty residents have signed a petition to remove the Senour Street entrance completely, but developers have yet to respond. Instead, they moved the entrance 200 feet south.

One of the main access points for semi-trucks into the facility is an entrance on Halsted Street, to the east of the warehouse. Halsted isn’t just a busy street for existing vehicles, but a popular bike lane: it’s just one of two bike lanes that cross the river between Bridgeport into Pilsen and UIC, and steps away from a busy Halsted Orange Line station.

“All of that traffic will funnel on Halsted southbound turning right” said Kate Lowe, an organizer with the Bridgeport Alliance and a professor in UIC’s College of Urban Planning and Public Affairs. She commutes to work on her bike from Bridgeport to UIC most days and won’t feel safe commuting on the bike lane knowing there will be hundreds of large vehicles turning across it. “It adds a lot of risk,” she said.

Even if there is a traffic light at the access point on Halsted, which Prologis said they will build, drivers of large trucks could miss a bicyclist on a right turn, according to Lowe. Crashes are not uncommon in an already congested area. A little further south, at the intersection of Halsted and Archer, there were ten car-pedestrian crashes and eighteen car-bike crashes from September 1, 2017 to November 17, 2020.

Residents and advocates are also worried about the pollution generated by the hundreds of delivery vans and trucks.

Richard Klawiter, an attorney with DLA Piper representing Prologis, noted that the “air quality impact is quite de minimis,” or negligible, and likened the impact to that of a “big box retailer”.

Advocates, however, say an increase in vehicle exhaust will increase the amount of particulate matter in the air, hazardous dust particles in the air that can contribute to chronic respiratory problems. Diesel exhaust from trucks also contain toxic compounds that increase the likelihood of cancer, according to a Chicago Reporter investigation.

In addition to pollution from emissions, dust generated from truck wheels, contaminated water runoff, light pollution, and ground vibrations can all have harmful environmental impacts, said Meleah Geertsma, Senior Attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC).

Bridgeport and other neighborhoods on the Southwest Side are already incredibly environmentally burdened; residents are not only more exposed to sources of industrial pollution, but they are also more vulnerable to its harmful effects. They often have a lack of access to healthcare, higher rates of asthma, and experience the compounded effects of existing pollution. Research also suggests that air pollution can worsen the effects of COVID-19, which already has disproportionately impacted Black and Latinx communities in the city.

Chloe Gurin-Sands, Manager of Health Equity and Planning at the Metropolitan Planning Council, said Chicago needs a planning process that looks at the cumulative impact of where logistics development is happening, and not just what’s going on at an individual site.

Shut out of the planning process

There are several aspects of the Amazon development that are frustrating to residents, but for many, the most galling is the city and developer’s apparent lack of meaningful engagement with the community.

According to a project timeline, Prologis began meeting with the Department of Planning and Development and 11th Ward Alderman Patrick Daley Thompson in June of 2019, a full year before the project was announced to community members in June of 2020.

The project they announced was also a near-complete one, according to residents who attended the Zoom meeting. The meeting was “geared more towards presentation and public comment, rather than true engagement,” the Metropolitan Planning Council said in their statement to the Plan Commission. The short timeframe between the meeting and when key documents were filed indicates it’s unlikely they made many changes based on resident feedback at the time. Prologis filed an eighteen-page application to the Plan Commission on July 22, 2020 and published a traffic study, dated July 6, 2020. “There’s only so much that people can comment on when you come with a plan that looks complete,” said Gurin-Sands.

At press time, Prologis and DLA Piper had only reached out to employees at the Metropolitan Planning Council, who suggested Prologis connect directly with community-based organizations. None of the other organizations or residents the Weekly spoke with had been contacted, nor did they know of others who had been. Both Prologis and Alderman Thompson declined to comment for this article.

“There’s zero interest in hearing from the community what we might want,” said Anna Schibrowsky, community development leader at Bridgeport Alliance. “That’s how it is: we can have input into how the lights are placed, but we have no say as to whether this comes in at all.”

Such lack of transparency around developments like Amazon’s is not new. In 2014, Chicago Helicopter Experience was approved, despite feedback against it from residents. In 2019, plans for the relocation of a food processing plant to Pilsen was presented as “a done” deal, again, despite opposition from community groups. More recently, the city has failed to be transparent with residents about multiple heavy-polluting industrial developments in South Side neighborhoods such as the MAT Asphalt in McKinley Park, General Iron in the East Side, and the botched implosion of the old Crawford coal plant in Little Village.

At the November meeting, Klawiter noted Prologis made changes to the site plan based on “extensive neighborhood feedback they received,” showing a before and after map of the site plan with more greenery, a riverwalk, and the addition of the former Heliport lot to the east of the original site to allow access to Halsted Street.

However, several changes were either required by law or decided upon prior to public notice. Multiple aspects of the project framed as “riverwalk amenities proposed”—a thirty-foot setback, public access to the riverfront, a riverwalk, benches every 250 feet—are basic requirements of any development along the river, according to the Chicago River Design Guidelines. Currently, the riverwalk only has one entrance on Halsted, where all the largest vehicles will be right-turning. Schribrowsky and other neighbors call it the “riverwalk to nowhere.”

The idea to add the heliport site was also one Alderman Thompson had suggested to Prologis before he announced the project to the community. “When I was first approached by Prologis for the former Grant Crowley boatyard site, I asked them to have a conversation with what was the heliport,” he said at the city meeting.

Ellen Grimes, Bridgeport resident and associate professor of architecture at the School of the Art Institute, is disappointed with what she calls the “greenwashing” of the project. Planting more trees around the perimeter of the site should not be a benchmark of sustainable development. According to Grimes, there were many more environmental measures beyond what’s required in city guidelines—solar panels, permeable paving to offset the heat generated by a large parking lot, or bioremediating infrastructure—that could have been implemented.

Aside from the requirements in city ordinances or zoning regulations, however, Grimes said any other promised improvements to the project are “just promises—they’re not bound to do those things.” That includes the promise to install EV charging stations or to use electric fleets, two points often cited by Prologis and the city when the topic of pollution is brought up. Amazon will not be required to follow restrictions on whether trucks only use the Halsted entrance, and not the residential entrance by Senour, she added.

The 200 permanent jobs that will be created, according to Prologis, are not guaranteed—there is no requirement for Amazon to create a certain number of jobs and Prologis cannot make that claim on behalf of them. “We need to complicate this question of 200 jobs,” said Beth Gutelius, research director at UIC’s Center for Urban Economic Development. “What are those jobs? Are they jobs we want our children doing?”

The soon-to-be minimum wage jobs offer little upward mobility, unrealistic efficiency standards, and constant surveillance, according to Gutelius. There are also numerous accounts of the negative physical and mental health impacts of Amazon jobs.

A Bloomberg analysis reveals that the arrival of Amazon warehouses actually brings down wages of other warehouse workers in the area. Research suggests many of these jobs may be lost due to automation in the future. Elected officials either promise lucrative property tax abatements and tax incentives, or Amazon applies for abatements and wins them – either way, Amazon facilities may bring a modest to minimal fiscal return for localities.

Even if Prologis had taken meaningful feedback from the community and improved the specifics of the site to their liking, advocates such as Gurin-Sands ask, “is that necessarily the point?” There will still be a warehouse that the community did not want.

For Raymond and other residents of Bridgeport Landing, the improvements “don’t change much” – the reality of living within several feet of an Amazon warehouse is still the same.

Warehouse boom

In many ways, Chicago’s geography, at the intersection of several major highways, waterways, and railways, makes the city a natural candidate for a burgeoning Transportation, Distribution, and Logistics (TDL) sector. In December of 2020, Mayor Lori Lightfoot announced that in the “coming months” Chicago will be “doubling-down” on efforts to invest in the TDL sector.

Commissioner Cox reflected this sentiment at the November city meeting: “We as Chicagoans have to accept that this sector is a part of Chicago’s future economy,” he said.

Yet, the boom of warehouse construction in primarily low-income and Black and Latinx neighborhoods is no accident. “Let’s be mindful that the land-use changes that have been occurring have created high priced properties on the North Side, removing those industrial locations, but where are they going? They’re going to the South, Southeast, and Southwest locations,” said Chicago Plan Commission Chairwoman Teresa Cordova. “Let’s not be disingenuous about that.”

In 2016, the City of Chicago began a process of evaluating and updating land-use policies in all twenty-six of the city’s industrial corridors, areas of the city that were specifically zoned for manufacturing or industrial use.

Although the majority of Industrial Corridor land is located on the city’s Southwest and Far South Side, the city began with the North Branch corridor, located along the river between Lincoln Park and Bucktown. In 2017, the city adopted the North Branch Framework Plan, rezoning areas from manufacturing to mixed-use and commercial uses. The North Branch is now home to Sterling Bay’s planned Lincoln Yards development, a fifty-five-acre “megadevelopment” that will include upscale offices and apartments.

But while the city has rezoned industrial land for mixed-use developments in affluent white neighborhoods, they incentivized manufacturers to move to designated “receiving corridors”, the majority of which are located in low-income or communities of color. Relocating manufacturers could tap into a fund created to help alleviate costs associated with the relocation, according to a city ordinance.

“It’s hard to view it as anything other than environmental racism,” said Geertsma. Instances of polluters moving into environmentally burdened communities are well-documented, the most recent example being metal scrapper General Iron, which is currently awaiting an operating permit from the city to relocate from Lincoln Park to the Southeast Side.

Prior to 2021, the Little Village Framework was the only Industrial Corridor Modernization Plan the city had adopted on the Southwest Side. José Acosta-Córdova, a research organizer at the Little Village Environmental Justice Organization (LVEJO), said the city only reluctantly agreed to Little Village after they put public pressure on them. The process was very different from the North Branch, however. Acosta-Córdova said they were initially only given a three-month process while the North Branch had over a year. There were also concerns with the community feedback timeline.

The lack of transparency only compounds the inequities. As with the Bridgeport facility, industrial and logistics developers alike have taken advantage of opaque local approvals to push projects through before residents can respond.

“There’s all this behind the scenes work that creates tremendous momentum and sidelines [our] voices in what happens,” said Lowe.

With regard to the Amazon’s Bridgeport warehouse, “if we were able to start those conversations beforehand, then maybe the outcomes could have been different,” said Gruin-Sands.

A long-term impact

Advocates are hopeful for change, though. The Chicago Plan Commission voted eight to six to approve the rezoning for Prologis in Bridgeport, a rare split vote in a committee that typically unanimously passes rezonings. At a January meeting, DPD announced they will initiate research for Far South and South West Industrial Corridor Framework Plans this year. The plans will look at land use and zoning, design guidelines for industrial developments, sustainability requirements, and freight impacts in those industrial corridors.

Unfortunately for residents of Bridgeport, Little Village, Gage Park, Pullman, and McKinley Park, all of this has come too late. Residents and organizers in Bridgeport were hopeful that the site, located near a Superfund site could be converted, envisioning a green, mixed-use, and transit-oriented development at 2420 South Halsted. One group had already started planning for future community uses. The South Branch Park Advisory Council (SBPAC) has spent the last two years gathering feedback from nearly 500 residents to put together a vision that included several green spaces and gathering areas for the community. There were also ideas to put the first neighborhood high school there, among other hopes to eventually connect all of Bridgeport’s waterfronts together.

That is no longer possible now, and it will take years to get the riverfront site back from Prologis. For a project deemed as a “test case” by DPD for what sustainable warehouses in Chicago will look like, the impacts to the community will be much more permanent.

“It’s going to change the future of the river and the areas adjacent to it for who knows how long,” said James Burns, resident and president of SBPAC.

*Names are changed for several residents who asked to be anonymous.

Note: An earlier version of this story misspelled Chloe Gurin-Sands’s name. The Weekly regrets the error.

Amy Qin is a contributor to the Weekly. She last wrote about how to vote in Chicago during the pandemic.

Excellent and thorough article! Thank you for connecting the dots regarding city officials disregard of the voices and well being of residents predominantly of color on the south, south west and south east sides – despite citizen alliances and expert documentation.

Such a waste of an incredible piece of land.