Only a writer with great confidence in her scholarly and narrative abilities would reserve a book’s most dramatic line for the acknowledgments.

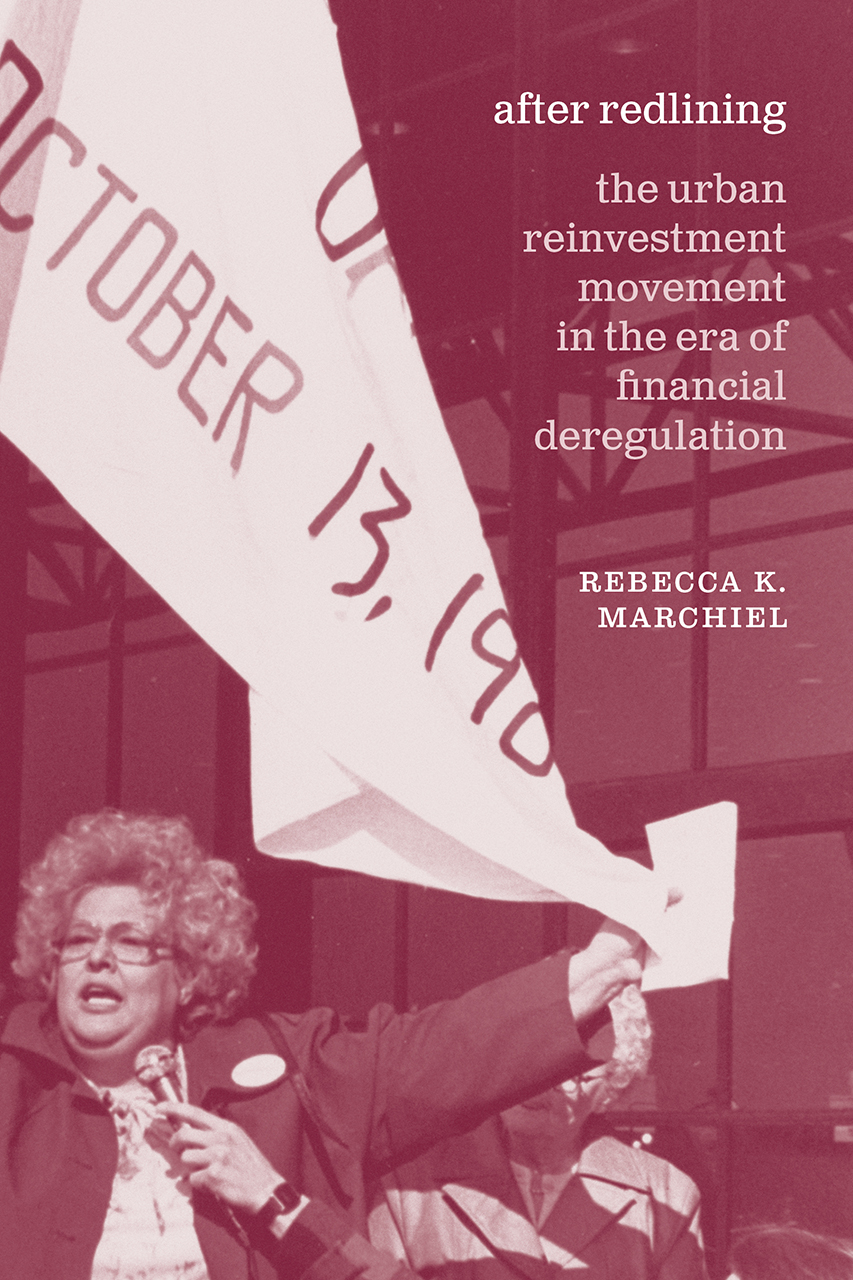

On the 237th page of After Redlining: The Urban Reinvestment Movement in the Era of Financial Deregulation (University of Chicago Press), author and historian Rebecca K. Marchiel writes, “This book began when I heard a lie on the radio in 2008.”

That lie was a financial industry lobbyist’s assertion that the Community Reinvestment Act of 1977, a landmark legislative achievement of the reinvestment movement that started on Chicago’s West Side, had caused the financial sector’s 2008 meltdown.

“I knew that wasn’t true,” Marchiel continues, “but I had a lot to learn to construct an alternative narrative.”

On this topic and others, After Redlining offers illuminating correctives to falsehoods advanced by the powerful and to what Marchiel calls “popular memory.”

From the mid-1960s into the early 1970s, whenever Black people first took up residence in an urban neighborhood populated by so-called white ethnics of meager or middling means, longstanding local lending practices changed. Savings and loan institutions known as “thrifts” reduced their lending activity in the neighborhood, despite holding the deposits of many residents. Local banks jacked up the percentage of a home’s total value that they required as down payment on mortgage loans. Thirty-year mortgages, with their affordable monthly payments, were suddenly more difficult to secure. The effect was to put home (and home-equity) loans out of reach for many who lived, or wanted to live, in racially mixed sections of American cities.

Municipal and actuarial complicity amplified the negative effects of reduced access to credit in what Marchiel calls “transitional neighborhoods.” Trash pickup became irregular. Educational funds that might have addressed overcrowding in public schools did not materialize. Underwriters doubled and even tripled the cost of home insurance.

Together, these conditions coalesced into a new kind of redlining in urban America.

Like the original redlining perpetrated by the federal government’s Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) in the late 1930s and 1940, in which mortgage loans were denied to buyers in Black neighborhoods deemed “hazardous” by the HOLC, the new redlining of the 1960s and 1970s propped up a “dual housing market.” Real-estate agents known as “panic peddlers” used racial animus, the prospect of rising crime, and predictions of falling home values to frighten lower-class white families into selling their homes on the cheap. The agents then sold those same homes, for multiples of the previous sale price, to Black families steered into a tightly limited housing supply by a conspiratorial network of lenders and real-estate operators. Black city dwellers faced further exploitation in the forms of fraudulent appraisals and predatory lending. “Contract selling”—essentially the selling of homes on an installment plan—prevented Black homeowners from building any equity in their homes until the purchase price was fully paid off, and allowed eviction and repossession by the seller, often as not a speculator, on the flimsiest of pretexts.

But in the West Side neighborhood of Austin, the new redlining and the dual-housing market it fed gave rise to a multiracial, multiethnic reinvestment movement that would register significant, lasting victories against a finance-realty complex content to hollow out American urban neighborhoods for profit. The movement’s origins were humble and hyperlocal. Organization for a Better Austin (OBA), led by Austin resident Gale Cincotta and organizer Shel Trapp, pursued three goals at its founding in June 1967: relieve overcrowding in Austin schools, develop programming for neighborhood youth, and “improve local housing conditions.”

By 1972, by means of tireless organizing and coalition building, OBA had transformed into National People’s Action for Housing (NPAH) and adopted a broad, urban-reinvestment agenda. With Cincotta and Trapp in leadership roles, NPAH pushed the federal government to reform the Federal Housing Authority (FHA) mortgage insurance program, which lenders used to earmark city blocks for redlining and profiteering. NPAH also agitated, Marchiel writes, for thrifts to lend “losable, uninsured capital to neighborhoods,” no matter “the age of their housing stock or the racial identities of residents.”

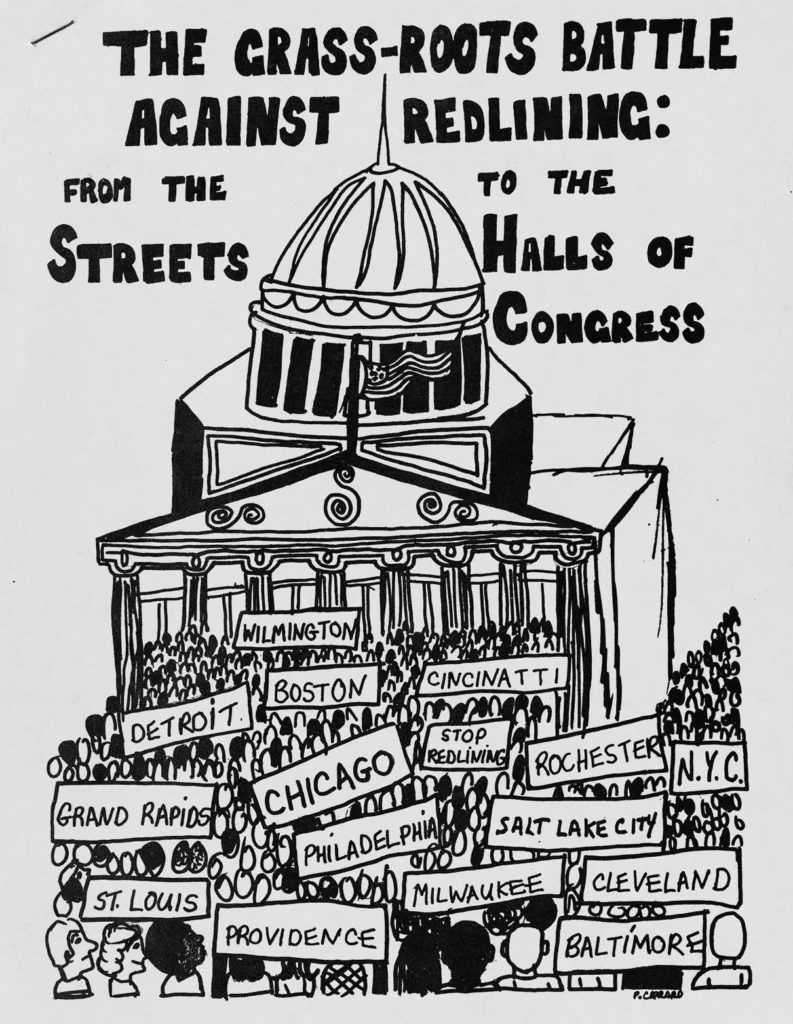

Even in the face of setbacks, reinvestment activists continually employed a go-bigger-or-go-home strategy, expanding their geographical reach and policy ambition. By the mid-1970s, NPAH had dropped “Housing” from their moniker, re-identified themselves as National People’s Action (NPA), and petitioned authors of the Democratic Party platform for a National Neighborhood Reinvestment Policy that called for disbursement of development funds in low- and middle-income communities, federal funding for anti-crime measures, affordable pharmaceuticals, and assistance for urban residents unable to meet the rising costs of utilities. In the late 1970s, activists added “dignified employment” and concerns about displacement to their issues list. By the 1980s, in the face of federal-government austerity programs and monetary policy that pushed home-mortgage rates as high as fifteen percent (up from a mid-’70s average of about seven percent), Cincotta and NPA were thinking in terms of “redlining by class” and forging alliances with labor unions and groups of family farmers.

Throughout her book, Marchiel connects the broadening of reinvestment activists’ policy goals to their burgeoning understanding of the systemic nature of what they had first experienced as distinct, local problems. As they discerned more clearly the powerful, interlocking forces aligned against the interests of their low- and middle-income communities, activists saw little choice but to grow their numbers and fight on multiple fronts.

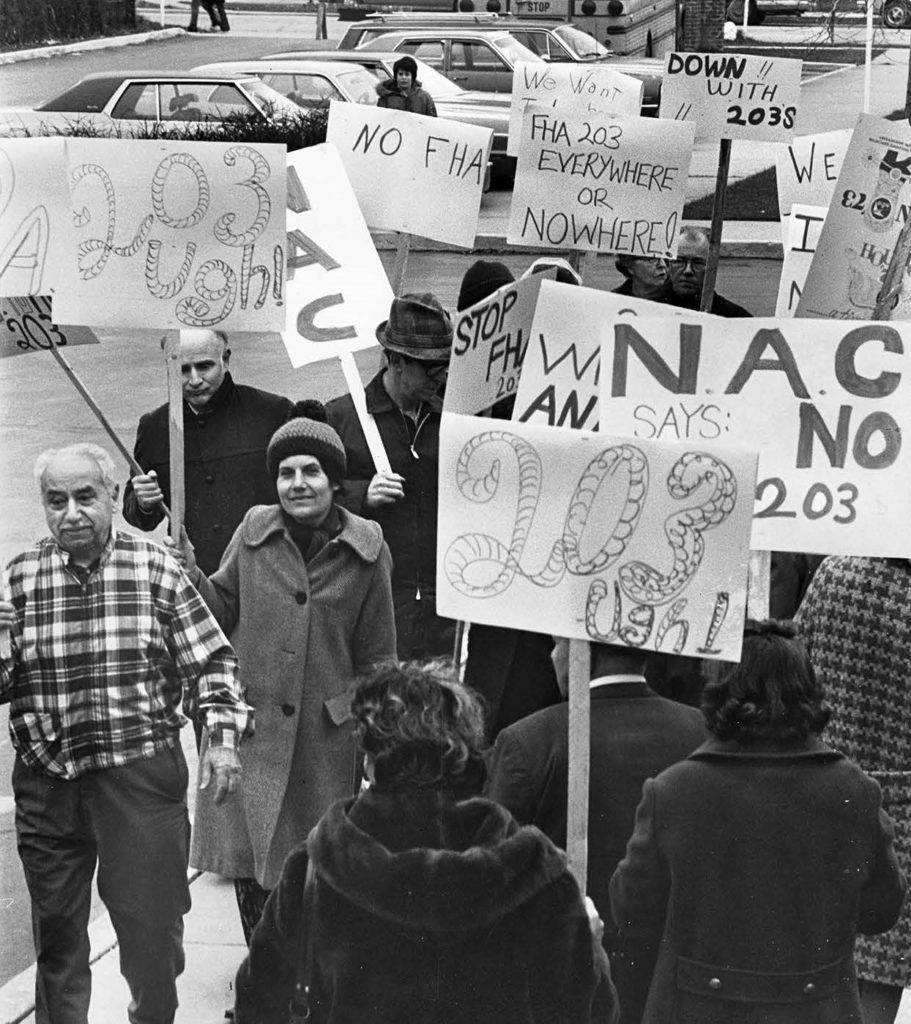

The national reinvestment movement was multiracial and multiethnic from its beginnings, a coalition founded on the principle, as Marchiel puts it, that “all urbanites suffered the effects of institutional racism when they chose to live in neighborhoods that weren’t…white.” Though it begat an all-in-this-together ethos that pushed racial and cultural divisions into the background behind reinvestment aims—a triumph of Alinsky organizing strategy—the founding principle’s conflation of the experiences and burdens of white-ethnic city dwellers with those of Black and Latinx Americans is problematic on its face. Indeed, the movement’s white leadership overlooked or misunderstood more than once the interests of their Black and Latinx members. In March 1972, at NPAH’s inaugural conference, Black and Latinx delegates headed off a resolution, sponsored and supported by white activists, to abolish the Federal Housing Authority’s mortgage-insurance plan. NPAH had correctly identified FHA insurance as a virulent tool of redlining. “Despite popular memory that attributes abandoned buildings and vacant lots to the fallout of the 1960s urban rebellions,” Marchiel writes, “1970s FHA insurance decimated the housing stock in the transitional neighborhoods where it was most concentrated.” Though bankers and speculators were misusing and abusing the program, FHA mortgage insurance also represented the only legitimate path to homeownership for many low-income Black and Latinx people. Enlightened by the lived experiences of its Black and Latinx delegates, NPAH resolved instead to call for reform of FHA mortgage insurance and for conventional, non-FHA home loans to be made to urban residents, without regard to race, thus expanding their opportunities for home ownership.

Marchiel’s account of the reinvestment movement’s racial and ethnic dynamics is at the heart of another corrective counter-narrative that animates her book. White flight was real—in Chicago, 399,000 whites moved to the suburbs in the 1950s alone. In white-ethnic neighborhoods, white flight deepened disinvestment rooted in restricted access to credit under HOLC yellowlining, the less severe, contemporaneous cousin of 1930s-era federal redlining. White flight was not an immediate, total exodus, however. Many white urbanites resisted both flight to the suburbs and the integration of city neighborhoods, committing acts of racial intimidation and violence, individually and en masse, as mobs, against Black families. Other whites who remained “crossed racial lines,” Marchiel writes, “to form community organizations that fought real estate abuse instead of their new [non-white] neighbors.”

Even as her portrait of cities as “fruitful ground for interracial politics where ‘blacks and whites were fighting banks, not each other’ ” runs counter to popular memory of white flight, it joins Marchiel’s history of the reinvestment movement to a body of scholarship about powerful, interracial coalitions that threatened the mid-twentieth-century status quo in Chicago and beyond. After Redlining makes a compelling companion to Jakobi Williams’s From the Bullet to the Ballot, a book that focuses on Fred Hampton, chairman of the Illinois Chapter of the Black Panther Party, and Hampton’s formation, in class solidarity, of a multiracial “Rainbow Coalition” in 1969.

After Redlining is, among other things, a tale told in two (legislative) acts. The first, the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) of 1975, was a major victory for reinvestment activists sick and tired of banks’ denials of geographic discrimination in lending. Activists had long demanded “disclosure”—specifically, that financial institutions report their lending activity by geography. Soon after President Gerald Ford signed HMDA into law, lending disclosures by institutions in Salt Lake City, Baltimore, and Lincoln, Nebraska, unveiled what the NPA called “drastic patterns of redlining and disinvestment.” HMDA disclosures gave activists the data they needed to pressure local lenders to make affordable credit available to low-and middle-income city dwellers. Even so, HMDA fell short of outlawing geographic redlining, and the practice continued.

The Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) of 1977—After Redlining’s second act—gave HMDA disclosures teeth. Under the CRA, reinvestment activist organizations were empowered to challenge formally the merging or acquisition of any financial institution shown to have discriminated against—or merely failed to lend in—the low- and middle-income communities in its area. Such a challenge opened negotiations between activists and the bank to lower barriers to credit in aging and transitioning urban neighborhoods. When activists were satisfied that their terms—ranging from low-interest loans for rehabilitating vacant buildings to the hiring of bilingual loan officers—had been met, and that accessible, affordable capital was set aside for their neighborhoods, the merger or acquisition was finalized.

The CRA abides as a remarkable devolution of regulatory power to activists—the law is still on the books today. However, as Marchiel demonstrates, any redlining that reinvestment activists did not spotlight remained undetected by federal regulators. In this sense, as much as it is a devolution of power, the CRA seems also an abdication of federal regulatory responsibility. Additionally, the CRA allocated no federal funds for aging and transitional urban neighborhoods. Reinvestment capital was to come from banks alone, and activists, though newly empowered, would have to wrest it from them.

Armed with the powerful combination of HMDA transparency and CRA regulatory power, activists won substantial capital for their communities. Between 1977 and 2004, Marchiel writes, “partnerships that grew from activists’ use of reinvestment regulations directed an estimated $1.7 trillion dollars to American cities…while increasing the flow of fair credit to minority communities.”

The storytelling in After Redlining is not limited to legislative maneuverings and dealings with ombudspersons. Marchiel surfaces accounts of activist sting operations, confrontational direct action, and disturbing governmental counterintelligence efforts.

In 1970, with its multiracial coalition fraying and Black members demanding new leadership, the OBA elected a Black man named Mark Salone as the organization’s president. Unbeknownst to the OBA electorate, Salone was an undercover Chicago policeman, part of the so-called Red Squad that, Marchiel writes, “targeted local political organizations like OBA that threatened to undermine the power of the local political machine.” Salone reported on organizers, missed meetings, and generally “botched” moments of opportunity for the movement. By 1971, the OBA was a “fractured organization,” albeit one still capable of coordinated activism.

Nor is After Redlining a history without heroes: the aforementioned Gale Cincotta, who remained an activist even after joining President Jimmy Carter’s National Commission on Neighborhoods; Shel Trapp, who schooled activists until his death in 2010; Tom Gaudette, trained by Saul Alinsky himself, who set Austin’s anti-redlining movement on a multiracial path; Ed Bailey, among the first Black homeowners in his section of Austin and an OBA member; Robert Kuttner, a staffer for the chairman of the Senate Banking Committee and founder of the magazine The American Prospect; Ron Grzywinski, a South Shore community-development banker who opened his bank’s books to educate activists and testified alongside them in favor of HMDA; Kristin Faust, a young banker who became an inside-industry advocate for profitable reinvestment that met the needs of low- and middle-income neighborhoods.

There is some dissonance, however, in Marchiel’s repeated mention of Black and Latinx activists’ valuable contributions to (and critiques of) the reinvestment movement and the relatively few Black and Latinx activists named in After Redlining at the movement’s watershed moments. In the book’s introduction, Marchiel outlines the limitations of her “primary archive, the unprocessed papers of National People’s Action,” which “did not provide significant insight into tensions within the [reinvestment] movement.” Given that the birth and growth of the reinvestment movement is still in living memory for so many, After Redlining should serve as a foundation for further scholarly investigation that puts additional faces and names to the vital role that Black and Latinx activists played in the movement’s formation, struggle, and success.

For all of its concrete legislative and financial victories, Marchiel considers the reinvestment movement a failure by its own metrics. Locally, “their attempt to create an integrated Austin ultimately failed,” she writes. Nationally, the federal government continued to rely on private lenders, not public funds, for reinvestment capital and stopped short of mandating the allocation of credit to low- and middle-income city dwellers. Development money earmarked for cities did more for city-center residential districts, such as Chicago’s Printers Row, than it did for outlying neighborhoods. In the end, the systemic tide still swamped reinvestment activists and their stakeholders.

Marchiel herself, however, largely succeeds in advancing a corrective counter-narrative to the lobbyist’s lie that inspired her writing and research. In After Redlining’s conclusion, she ties up the threads of financial deregulation that run through her history of the reinvestment movement with an argument, convincing though brief, that deregulation itself set the stage for the 2008 housing-market crash. Storefront mortgage lenders, the core of what Marchiel calls “an unregulated financial service industry” not subject to activist-as-regulator interventions under the CRA, proliferated in the 1980s and 1990s, exploiting low- and middle-income borrowers, many of them Black and Latinx, with interest rates as many as three times the market rate. Deregulation also enabled further securitization of mortgages. The packaging and repackaging of mortgages as securities contributed to the crash while making it harder to identify the individuals and institutions responsible for it.

After Redlining joins the ranks of scholarly histories highlighting Chicago as the imperfect locus of grassroots, multiracial, multiethnic activist organizations that changed the status quo of their time in ways that still ameliorate aspects of our unjust present. What is more, Marchiel’s account of the reinvestment movement’s go-bigger-or-go-home strategy offers a relevant historical perspective to contemporary activists who face, along with the communities for whom they advocate, a treacherously uncertain future.

The reinvestment movement abides today as People’s Action (PA), an organization with legacy ties to the NPA, Alliance for a Just Society, USAction, and other groups. Housing reform remains a focus of the modern PA, among a host of other campaign causes: health care, climate justice, and family economic security among them. This wide array of policy objectives and PA’s rural organizing efforts reflect the reinvestment movement’s hard-earned knowledge of the interconnected, systemic nature of economic crises.

The existence of a vibrant, national, present-day incarnation of the reinvestment movement raises a stubbornly troublesome dimension of Marchiel’s book: its title. Though reinvestment activists may have stamped out the specific form of redlining that plagued American cities in the late 1960s and 1970s—no small achievement, this—contemporary urban America has still not entered, in any meaningful way, a post-redlining period. A recent WBEZ and City Bureau collaborative report showed that from 2012 through 2018, Chicago’s majority-white Lakeview neighborhood received twelve times more lending capital than was disbursed in the majority-Black Austin neighborhood. Banks made more loans in majority-white Lincoln Park than in all of Chicago’s Black neighborhoods combined.

Moreover, according to a working paper published by the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago after Marchiel’s book had gone to print, the original federal redlining and yellowlining of the 1930s is still harming hundreds of thousands of Americans, many of them Black and Latinx, now in their thirties and forties. The Chicago Fed’s analysis of urban cohorts “born in the 1970s and early 1980s” found that HOLC redlining and yellowlining had “a causal, and an economically meaningful, effect on outcomes like household income during adulthood, the probability of moving upward toward the top of the income distribution, and modern credit scores.” In other words, if you were born some three decades after HOLC maps were inked, on a block that the federal agency saw fit to code in red or yellow as being at higher risk of mortgage default, you likely make less money, enjoy less economic mobility, and suffer disproportionately limited access to credit compared to peers born just a few blocks away, across a line no less real for its near invisibility.

Redlining is not over. It evolves even as its negative outcomes compound.

On February 4, 2021, as reported in Crain’s Chicago Business, Chase Bank opened a branch in South Shore, part of a response to reports of the bank’s discriminatory lending practices in Chicago. Chase CEO Jamie Dimon announced the bank’s “targets” to provide “$600 million (over the next five years) in new mortgages for Blacks and new homeowners in Chicago neighborhoods.”

Should the funds make their way into the hands and homes for which they are intended—and histories such as Marchiel’s sow doubt as to financial institutions’ sincerity and commitment—another successful community-development partnership can be added to the running list. But it is difficult to conceive that any private effort, any more than the gaudy billions lent in deals struck under CRA-enabled activist regulation, can achieve scale significant enough to overcome the exponential negative impact of lending discrimination past and present. Either the federal government originally and recidivistically responsible for redlining will turn the systemic tide, or Black and Latinx residents of American cities will remain underwater.

Rebecca K. Marchiel, After Redlining: The Urban Reinvestment Movement in the Era of Financial Deregulation, The University of Chicago Press, 296 pages.

Dave Reidy is the author of two books, including The Voiceover Artist: A Novel. He last wrote for the Weekly about the history of yellowlining on the Southwest Side.