The man dancing at the edge of the stage moves with an energy rare for his seventy-plus years. He dips and bobs, a harmonica pressed to his lips. It’s December 2014, and the man plays for an excited crowd at the Mayne Stage theater in Rogers Park. Behind him, the much younger members of his backing band play with a kind of long-suffering acceptance, aware of how overshadowed they are.

Charles “Organaire” Cameron was in his early thirties when he arrived in the United States in 1976, leaving Jamaica with a musical legacy already established there. A performer from his earliest days, Cameron is best known as a session musician for some of reggae’s most famous faces, including Jimmy Cliff, Toots and the Maytals, and Bob Marley.

Amid the political unrest of the early seventies in Jamaica and his personal frustrations with the politics of Jamaican music labels, Cameron made the jump to Chicago. He established a separate life and career, one that has spanned over thirty years, in a city where he never intended to stay. Cameron is considered a “foundation musician” in Jamaica, having helped create the genres of both ska and reggae. Yet he never gained much traction as a solo star in the country known for his music, and in his adopted country recognition for his past contributions has been basically nonexistent.

But now, with the help of a superfan, Cameron is making a resurgence, becoming known in his own right as co-father of a genre, whose two lives—one Jamaican, one American—are finally converging.

Sitting in a Hyde Park coffee shop, Cameron talks about his musical beginnings, voice moving in the same stutter-start time of the music he has carried with him since Jamaica. He holds himself in an easy manner, slightly stooped, with worn hands and an open, friendly face. The corners of his eyes crinkle as he paints a picture of his history. Next to him sits Skandar Skandal, the owner of Colibri Records and a Chicago-based artist who helped rediscover Cameron in 2012. Last year, Skandal and Colibri put out a limited-edition record of Cameron’s new tracks.

Born in Jamaica in the early forties, Cameron picked up a harmonica at age five and has hung onto it ever since. “I always liked the sound of it,” he says. “I have a bunch of guitars, and I still don’t play. I still haven’t played a guitar.”

Soon he was performing in local talent competitions, where “there was a prize for the winner, and they booed for the losers. Fortunately I didn’t get too many of the boos.” From there he progressed to nightclubs around the island, playing, he recounts, “everything.”

“Jamaican musicians play every music,” he says, laughing. “You know, I don’t put a limit on music. There’s always something nice in the music, so I listen to everything.”

Soon he was playing regularly with several other foundation musicians— Arkland “Drumbago” Parks, Theophilus Beckford, Jah Jerry. These and others also provided instrumentals for Jamaica’s main ska and reggae music producer, Studio 1, part of a series of studios reminiscent of Detroit’s Motown, both in influence and sheer scale of production.

“We got paid for each side,” Cameron says. “So we tried to get as many as we could.” By his estimate, he appeared on over three thousand sides of records between 1962 and 1969.

This means that Cameron and others turned out a vast number of tracks at an incredible rate. “The way we recorded them, is everything live,” he says. “We had one recording studio, and each producer recorded in the same studio. One finished, then the other took over. So we start at 9pm to 3am. We [didn’t] know the name of the song, especially instrumentals. The producers are the ones who put the title in there. The only ones we know the titles on are the ones where people sing.”

Skandal adds an important tidbit: “The session was live. Just a mic and a two channel mixing track. If they missed [a track], which they did occasionally because they were experimental musicians, they had to start again.”

Cameron essentially provided the soundtrack of a nation and the barebones of a genre, but couldn’t tell you the titles of the vast majority of the tracks he soloed and performed on.

Despite this prolific output, Cameron and other session musicians were often shortchanged by their producers. “The record producers weren’t treating us right,” Cameron remembers. “For example, you work for someone, they have the money in their pocket to pay you, but they feel important—super important—so they tell you, ‘Come back tomorrow.’ ”

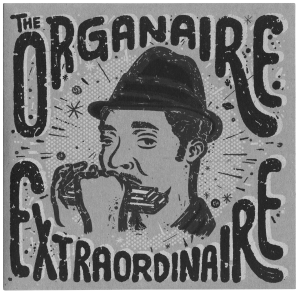

In this landscape, Cameron took matters into his own hands. He created his own label, named it “Organaire Records” after a childhood nickname, and began self-recording, producing, and releasing original music.

It still wasn’t enough. He remembers a time when, despite having a popular solo record, a track called “Elusive Baby,” he failed to get any airtime in Jamaica. The producers, angry at his unwillingness to play by their rules, pulled Cameron’s songs from the radio.

So Cameron came to Chicago. When he first arrived, he settled on the South Side, near 95th Street and South Avalon Avenue in the Burnside neighborhood. Cameron played everywhere he could, including Greek restaurants and Jamaican parties, but especially for the city’s Latino population: the Cuban, Puerto Rican, and Dominican clubs. Cameron recalls a South Side filled with performance venues, including the Bamboo Club, across from the South Shore Cultural Center.

With the help of Jayde Enterprises, one of the first black-owned talent agencies in Chicago, Cameron began getting booked for larger events around the city. He played for mayors Jane Byrne and Harold Washington and at events such as ChicagoFest, an annual music festival in the seventies and eighties.

But that, mainly, was it. There was no fame, no great wealth, and most importantly, no real recognition of who he had been in Jamaica. Laughing, he says, “Now I’m stuck here, and now I have a family here.” He never rose higher in prominence, certainly never to the level of a pioneering member of one of the world’s most expansive and influential musical genres. He became a member of the Chicago Painters Union. During the day he painted building exteriors, and at night he gigged, for thirty-odd years.

This is where Skandal comes in. An artist based in Logan Square, Skandal produces paintings and murals, as well as vibrant artwork for Chicago publications (his work has been featured in the Weekly). He has a rabid appreciation for old Jamaican music, and has spent much of his life collecting archival ska and reggae records. The label he started in Mexico City, Colibri Records, comes from the Spanish name for a species of hummingbird endemic to Jamaica. It moved with him to Chicago when he arrived four years ago.

Skandal first remembers meeting Cameron in 2012 at a celebration commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of Jamaican independence in Kenosha, Wisconsin. After hearing Cameron’s name from a Chicago connection who was familiar with the scene in Jamaica, Skandal took a bus, a train, and a cab just to meet Cameron. Back in Chicago, Skandal presented Cameron with the first record Cameron ever put out, from 1963. As Cameron puts it, “He said, ‘Charley Organaire.’ I said, ‘Well you know something about my history.’ So we started talking.”

It turns out that “Cameron,” the name he had been performing under in Chicago, was unrecognized in Jamaica. He had performed under “Charley Organaire” when he lived there, after the childhood nickname given to him by a neighbor based on Cameron’s ever-present mouth organ. This meant that to many fans of his old music, including Skandal, he was dead—or, at least, had not performed since the early seventies.

Cameron, leaning back in his chair, eyes twinkling, tells about how a bass player who had played with him for years in Chicago didn’t know about his Jamaican roots. “One day he said to me—he called me Daddy Charles—‘Daddy Charles, all these years I’ve been dancing to your music and didn’t know?’ ”

Skandal’s mission, then, is to reunite both sides of Cameron’s musical past. As he explains it, “Charley is one of the Jamaican pioneer musicians from the islands. One of the most well-known reggae musicians is Bob Marley, but Bob Marley would be considered third generation. Charley is the first.” There is a deep desire on Skandal’s part to make the world aware of this. “What we have been doing is trying to rescue his old stuff.”

He pauses to pull out the first record his label, Colibri Records, has made with Charley. It’s one of only five hundred pressed, with the intention of making it a collector’s item for diehard fans like Skandal. “This has been aimed at the public that has been following Charley since he was recording in the sixties,” Skandal says. On the inside is a photograph of Cameron in a porkpie hat, straight out of his days in Kingston. The tracks are all new, written and arranged by Cameron and Skandal. They’re recorded in an old-school style, an attempt to capture the sound in the music Cameron put out in the early days of reggae. The record is also Cameron’s first recording on vinyl since the sixties.

Skandal’s mission is clear: to share, and add to, Charley’s legacy. But he has his work cut out for him. “Charley is very humble and he doesn’t like to talk about himself,” Skandal admits.

However, with his two names finally combined, a just-completed European tour with Minnesota backing band the Prizefighters, and more recordings and performances slated for 2015, Charley “Organaire” Cameron isn’t in danger of fading into obscurity anytime soon.

The Mayne Stage show last month was part of a series designed to expose Jamaican foundation music to a larger audience. Chuck Wren, the owner of the Jump Up! record label that put out another Cameron record, this time with the Prizefighters accompanying, organized the show and comments on Cameron’s influence: “Charley’s presence at our shows made the Jamaican singers feel comfortable…[there’s] nothing like seeing an old friend after decades.” Wren is quick to add, “It’s funny, I think his true Chicago legacy has only begun.”

It’s this union between Cameron’s past and present that affirms his staying power. Plus, he’s surely stuck it out. “I’ve been here a long, long time, he says. “But you never know. When the right time comes, it’s the right time, doesn’t matter when. The thing I always do is just to continue what I’m doing. Never stop.”