Damon Lamar Reed, a forty-seven-year-old acrylic painter living in South Shore who’s participated in the majority of mural restorations in Chicago over the last decade, was named the inaugural Artist of the Year in December by the leading public art group in the city.

Graduating from the Art Institute of Chicago in 1999, Reed was first introduced to the possibility of doing murals as a career after he met Bernard Williams, a member of said artist collective, the Chicago Public Arts Group (CPAG)—previously known as the Chicago Mural Group—who took him under his wing as an outdoor mural assistant.

Since then he has worked on hundreds of murals, independently and in collaboration with CPAG and CPAG artists such as veteran muralist John Pitman Weber.

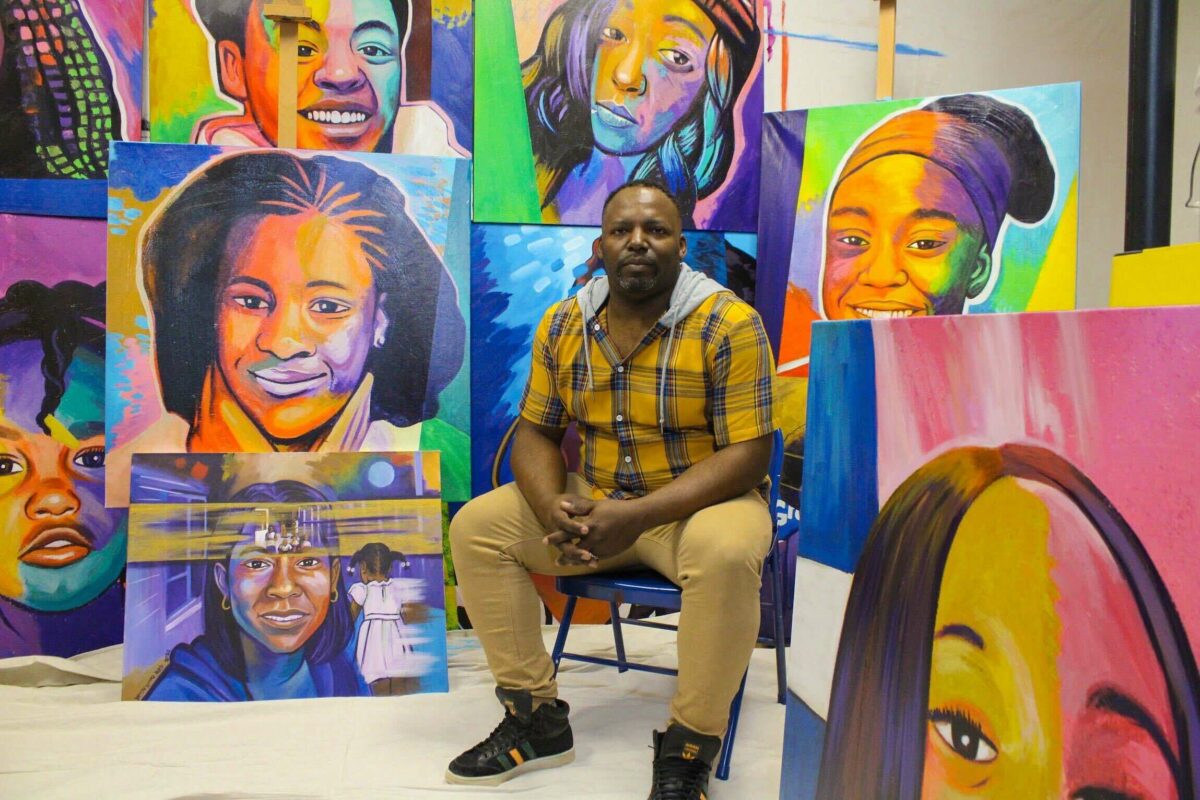

Reed’s artwork is characterized by a palette of bright primary colors, symbols representing the city (think the L train, greystone houses, the skyline), and portraits of community members—especially children—interacting with or embodying a sense of hope and potential that is larger than life but not elusive.

One of his ongoing studio projects is a series of more than thirty portraits of women and girls who’ve gone missing in Chicago—often with the blessing and involvement of the victims’ families. “For more than twenty years, African American women and girls have gone missing across the United States, unprotected by law enforcement, the media, or the public,” CPAG said in a statement. “Reed is calling those Chicago victims to our attention with Still Searching.”

Reed calculates having done murals in more than eighty CPS schools, charter schools, and other school districts, as well as across state lines. He has recently found himself mentoring young artists and is designing a course to teach other talented peers how to make their art sustainable. He also wants to keep experimenting with new mediums.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

When did you paint your first murals?

I was either a junior or senior in high school. Once I was in college, I actually wanted to be a children’s book illustrator. I was in my last semester at the Art Institute, in a history of mural painting class, and this artist, Bernard Williams, came in and he showed his artwork and talked to the class. And I was like, “Well, how much you get paid for that?” And then I’m like, “Okay, man, this is cool.” And we went on a field trip to see his murals, and I showed him my portfolio while we were on the train. And then he was like, “Okay, well, I may need an assistant for a project coming up.” And I would say, like, two months later, I was assisting him, and that was also my first project with the Chicago Public Art Group.

When it comes to murals, do you work on the painting off-site and then install it (as has become more commonplace) or do you work directly on the wall?

When I was first doing murals, we definitely did it on site. Now I’ll maybe say like 80% of them I do on polytab and then adhere to the wall. So we are [still] on site, but not for as long. I actually first started using polytab when I was having my first daughter, and I wanted ways where I could be at home more, so now it kind of works out, because we can kind of work at all times. The weather doesn’t restrict us, or like office hours, or sunlight, or anything like that. Sometimes we work all-nighters and then we don’t have to kind of bother. If the mural is for a business or a school, those hours kind of don’t matter as much. And then we can just go install it. And that could be either a few hours, or it could be some days, but it’s definitely a shorter span.

What do you find appealing about doing restorations? Is it just bringing something back to life?

Beside being able to bring it back, an historic piece of art, especially like restoring a Calvin Jones or a Bill Walker piece, who are Chicago mural artists, who were, to me, like Picasso…it’s [also] fun for me [because] a restoration is about matching the artist style. And that’s real fun to me, just being able to like mix those colors or mimic the style that they did. And it makes you [learn] its techniques. You could even be like, “Okay, now when I do a mural, maybe let me try this technique or that technique…” because techniques they were using in 1975 a lot of times are different than things we are using now.

The point you’ve made about murals being fine arts, is that something that you saw at the Art Institute?

At the Art Institute, I didn’t know anything about murals, literally, until that last semester. I never even knew you could make it a career in, like, being a mural artist or nothing. The Art Institute taught me a lot about conceptual art, which I don’t say I’m anti conceptual, but to me, a lot of the art at the Art Institute was more ambiguous. And with all of my art, I have something that I want the viewer to get out of it.

Do you think the attitude toward murals is changing in art school, whether it’s the Art Institute or in general?

I feel like it wasn’t many students who really knew about… I mean, of course, people know about graffiti and things like that, but the fact that you can make a career out of painting murals, I still don’t think that’s really widely known. And I do know that they’ve had a mural painting class at the Art Institute before, but I don’t think it’s really taught that that can be a career.

I actually had a mural master class that I led a few weeks ago that was based off of a grant I got from DCASE (Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events). It wasn’t a skills class. So I kind of advertised it like, “this is not a learn to paint class.” It’s for people who already know how to paint, but who want to actually figure out how they can make money doing murals. When I graduated, nobody taught me how to make money doing art. I actually took a business class at the Small Business Administration when I first graduated, about writing a business plan, things like that. And, more recently, I took classes at the South Shore Chamber of Commerce, which had a small business program. And then Sunshine Enterprises had a small business, or, like, an artisan program, and, you know, just constantly educating myself on marketing and things like that, even finding classes on YouTube. And I think that’s kind of what’s missing in the art field, it’s a lot of good artists, but a lot of them maybe haven’t learned, “How can I actually do this as a career?”

If you could give one free piece of advice to artists about how to market your art, or anything that might help them out, what would you say?

I’ll say the biggest thing in marketing your art, is marketing yourself. It’s about telling your story, like, each art piece can be its own story that you’re telling. You gotta tell your story.

How would you describe your style?

I like it to be bold, normally colorful, but it can be bold without—I mean, you can have a kind of a minimal palette and be bold. But when I say bold, it’s in a sense, like, I want every one of my murals and every one of my art pieces to be memorable, so I’m not like cookie cutter when I’m doing it. So I wanted to be bold. I want to tell a story.

I’ve noticed you’re doing portraits within your paintings. There’s references to sports, different Chicago things, or landmarks or icons.

I like to have contrast. And I feel like there’s even a contrast, or a kind of duality even within the art itself, and I think that’s part of the story. Like what’s that saying? You can’t really know the good without the bad type of thing. So, like every good movie, you got the protagonists and the antagonists. Part of telling that story is kind of showing that whole thing.

What would you say are your most popular paintings?

The Chicago Boy painting, as far as canvas paintings, because that one, I don’t know, it somehow connects with everybody, and that’s why I even made prints and hoodies and stuff of that image. And then if we’re talking about murals, I’ll say I have this mural in Memphis that’s real popular called the Sound of Memphis. And it’s this guy holding a guitar, and on the guitar is like stickers of the history of Memphis. When I put it up, I did it in 2015, they said it was going to be up there like two years. And it’s still up. I guess they call it one of the top Instagrammable spots in Memphis. Different TV shows have used it, this children’s book just used it.

What does the Chicago Boy painting mean to you, or what did you hope it would mean?

On a mural we did in Woodlawn, we had put this Oscar Brown Jr. quote on it. And I’m not sure this is the exact quote, but it goes something like, “a small boy walked down the city street and hope was in his eyes.” So that kind of sums up my idea of Chicago Boy. It’s this boy, and on one side you have the city lights, it’s the Chicago downtown. But then on the other side, you got this basketball hoop with no net. And it’s kind of like at that point in his life where he has to make a decision on what kind of path he is going to take. But he does have the stars of Chicago in his eyes. And also things that I thought about when I did that painting was, like, working in a lot of schools, it would be a lot of kids who had never been downtown or to Navy Pier before. And they’re from Chicago, they grew up here, but they don’t get outside of their own neighborhood, you know? So I was kind of thinking about all those things.

So has the boy in the painting already been downtown or is he dreaming of going downtown? Or you’re not sure, he’s somewhere in the middle.

Yeah, I think he’s in the middle. I would say he, I mean, my optimistic self, I would say, yeah, he’s been downtown and you know he’s gonna be a successful young man. Like I said, I’m an optimist.

I think the painting does transmit that energy. I saw hope in his eyes. And my other favorite element, I think, was the train, basically crossing the entire width of the painting.

And that kind of symbolizes, I mean, the train in Chicago is kind of like a symbol of movement, you know, like going forward. So that adds to that.

Are there other cities that you’ve gotten to where you have big works of public art?

I have works in Indiana; Gary, Indianapolis and Richmond. Actually, I have some work in Texas, at the University of Northern Texas. I have work in Florida at Gulf Coast University. I have something in Detroit, I think it’s like a jazz museum. And Maryland, Arizona, at the South Phoenix Youth Center—I kind of grew up going there, and then they asked me to do a mural that was like my second out-of-college mural. Oh, and I have a big mural coming up in Alden City, Utah.

You also did a lot of work in schools, right?

Yeah, a lot of CPS schools, and in a few schools I’ve done a lot of murals. There’s a school, John M. Smith, which is right off Roosevelt, and it’s like, right by the old Maxwell Street. I think I have like maybe seven murals on that school, and it’s like four of them on the outside of the school.

I am a vendor with Chicago Public Schools, so schools can just hire me. Before I was a vendor, I was working with other organizations, and they would hire me to do a project. Like, for instance, the principal at Smith saw me. I was actually across the street from the school doing a mural and he saw me, and he walked over, and he’s like, “Hey, I want you to do something at the school.” And we built that relationship. There’s another school called Aldrich. I have about ten murals there. And there was a principal there, we worked together a lot, and now the new principal, I’ve done a lot of work with her. I’m always trying to build relationships. Oh, this school, King Academy of Social Justice, I have probably nine or ten murals in there, too.

Tell me about the Artist of the Year award.

It’s the first Artist of the Year award that they’re giving out, which is super cool. I’m really honored to be receiving it. And I would say, I’m a child of Chicago from the Public Art Group lineup. My first time assisting, like I said, was on this Bernard Williams mural project, and that was a Chicago Public Art Group project. When I started with them, they kind of had a system where you would be an assistant a certain number of times, and then I became a co-lead artist, and then I graduated to a lead artist. So, yeah, I learned a lot about doing murals from artists working with Chicago Public Art Group. And I started working with my first project in 2000 and from then, up until now, I still work with them. My art career kind of grew up with them to now where, like, I’m having my own assistants, and I’m doing my own projects, and kind of building up my own thing. And, yeah, I owe that a lot to Chicago Public Art Group.

So talking about the future, looking ahead. You mentioned that you are going to be working out of state. You’re also doing some sculptures. What do you think is coming for you in the next few years?

Definitely bigger projects, mentoring more artists. But one thing I want to do is establish myself as a leader in the mural movement. So maybe consulting more, training other young artists to do it. And then on the other side of the business, putting out different products that are just gonna kind of help me build my legacy and the art world.

I definitely want to experiment, I have a lot of ideas. I probably got like twenty ideas that I just haven’t had time to do yet. Like, that’s why I don’t understand how people get bored. Because I’m always like, man, I need more time to do things. Like I’ve been wanting to do a fresco. I’ve done a small fresco [before], I learned how to do one. But I’ve never been able to make a fresco mural. That used to always be a goal. I want to take it back and do, like, you know, Diego Rivera, do a couple just of my own fresco murals.

Jacqueline Serrato is the Weekly’s editor-in-chief.

I am so thrilled that Damon got this award. He so well deserves it. I look forward to seeing more of his work around the city. I hope someday, somewhere, he can work with youth and young adults experiencing homelessness. Art can be transformational, not just for the viewers who experience it but for the young people who co-create it.

his article is such an inspiring and insightful look into Damon Lamar Reed’s journey as a muralist! I love how it highlights his dedication to public art, his unique style, and his commitment to telling meaningful stories through his work. The way he blends bold, colorful imagery with themes of hope and community is truly captivating. It’s also amazing to see how he’s mentoring young artists and pushing the boundaries of his craft. The personal anecdotes and reflections make the piece feel intimate and engaging. Great job on showcasing such a talented and impactful artist!

How does Damon Lamar Reed balance his work on large-scale murals with his smaller studio projects, like the “Still Searching” portrait series?