This story was co-published in partnership with The TRiiBE.

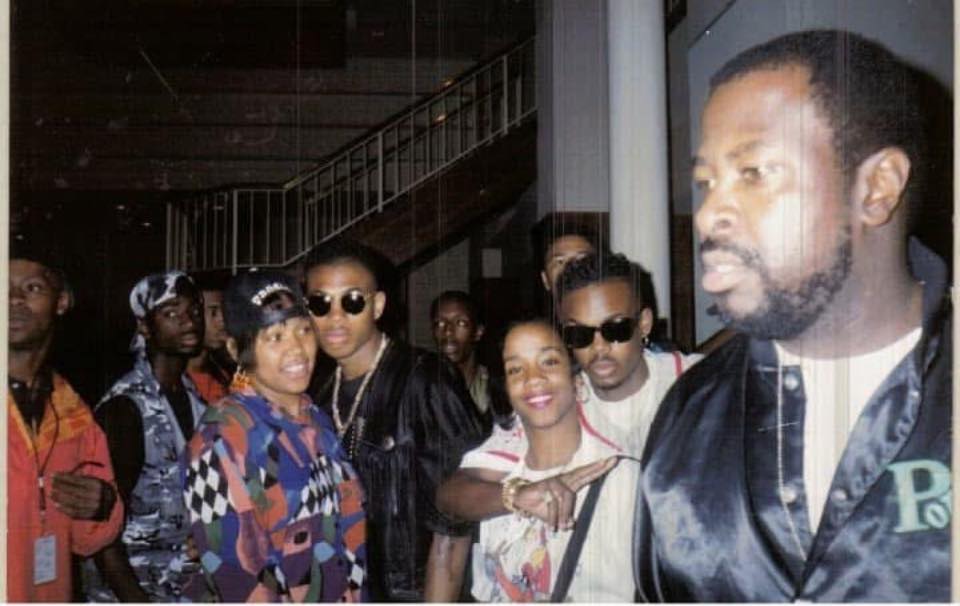

Back in the 1980s and 1990s, the Southwest Side’s Ford City Mall and far South Side’s Evergreen Plaza were places where teenagers were welcome to congregate, meet with friends and hang out on the weekends. Chicago had multiple skating rinks, teen clubs, bowling alleys, school-sponsored House parties and welcoming spaces — often called third spaces — where teens could kick it.

Those were different times. Today’s malls have “youth escort policies,” prohibiting the tween and teen set from going to the mall by themselves on certain days unless accompanied by an adult over twenty-one years of age. Outdoor events have become heavily policed. Most skating rinks have closed. Bowling alleys are in decline. And teen clubs? What’s that?

All those places, these “third spaces,” were locations that welcomed Gen-X Chicago kids (and the oldest of the Millennials) as a gathering spot to just, be, outside of home or school. Those spaces have largely disappeared. Mall culture, for example, nearly died as online shopping and social media-inspired dropshipping consumed the consumer. Accidents, shootings and insurance issues led to the closure of teen clubs. So today, the third space for the under-twenty-one crowd has not just eroded, it just might be extinct.

“I graduated high school in ’96, so let me tell you, my older cousins and siblings, they were from the era when house music first started,” said Malika McCollum, forty-six, who grew up in Auburn-Gresham and Roseland. “So when I was little, I was so fascinated. I couldn’t wait to get in high school to go to the parties.”

McCollum remembers the club scene back then. Those parties shaped the house music genre in Chicago. She spent her four years in high school dancing and partying — safely, due to the city’s youth-centered social scene.

“We had all these different dance groups,” she said, fondly naming the 1990s Chicago dance group House O Matics. “We had talent shows, hair competition shows, where everybody would go and dance throughout the city in different neighborhoods.”

Schools also played an essential role in the teen social scene of the 1970s and ’80s. During a 2019 panel about high schools’ role in the house and dance scene, house DJs such as Celeste Alexander and Kirk Townsend detailed why school “sock hops” were pivotal.

“When Mendel was doing parties, kids were coming from all over the city, and they were there to party,” said Townsend, who is credited by the Chicago Black Culture Map as the teen party promoter who DJ’d at Mendel High School from 1975 until the school’s closure in 1988. “If they wanted to [go to] war, there were the dance group wars, where they did dance-offs.”

Austin resident Gheri Marshall remembers riding her bike with friends from the West Side to the North Side. She also remembers going to school-based parties, or “sets.”

They used to send out these things called pluggers,” said Marshall, sixty-five. “And everybody knew about these parties. That’s when they were playing the albums, long versions. And we would just have a ball.

School sets eventually lost their luster due to the rise of gang violence in the city. According to Honor, Violence and Upward Mobility, A Case Study of Chicago Gangs During the 1970s and 1980s, gang activity in Chicago increased in 1979, with “a large number of gang-related murders” occurring by 1981.

House music recording artist Danielle Sanders said that in her experience as a mother, she’s seen how violence, as well as cuts to school funding, have led to the decline of school parties.

Teens once found solace at clubs like Medusa’s in Lakeview, which offered a space for young adults to dance the night away in the company of their peers. It opened in 1983. By 1986 Medusa’s became known for its community of teen-aged alt-music lovers. The nightclub, or “juice bar,” as it was called due to being an alcohol-free establishment, was popular with young adults across Chicagoland. It was also a haven for LGBTQ+ youth.

Medusa’s, which opened after the closure of the Warehouse — the historic club credited for the start of house music — further propelled the genre forward with its all-age parties that would start after midnight and last until 8:00 in the morning.

By the late ’80s, Medusa’s drew criticism from some neighbors in the 44th Ward, with some complaining of noisy and wild behavior from the teen clubbers. As a result, then-44th Ward Alderman Bernie Hansen pushed for an ordinance forcing juice bars to close at 2:00 a.m. on Friday and 3:00 a.m. on Saturday. Medusa’s closed in 1992 after the building’s owner refused to renew the club’s lease or sell to the club owner.

Sanders spoke on the prominence that youth-centered clubs once had in spaces like the South and West Loop. Sanders said that downtown revitalization efforts led by former Mayor Richard M. Daley made the area more of a tourist attraction and less of a city kid hangout.

“That was like a big deal, Daley kind of gentrifying and beautifying the area,” Sanders said. “A lot of those [teen and adult] clubs were in the South Loop. There used to be a row of clubs. They all got shut down for various reasons. A lot of it would be noise, especially as the condos came up.

In 2001, Daley proposed an ordinance that would allow criminal penalties to be levied against building owners and managers who allowed drug use and solicitation, according to the Tribune. It was followed by the 2003 federal RAVE act, a byproduct of the 1980s- and 1990s-era War on Drugs, which fined and jailed party promoters if drug activity was found on their premises.

The crackdown in Chicago could be correlated to teenagers shifting to suburban areas to party the night away. Growing up in Harvey, thirty-six-year-old Chimeka Heard-Powell says the party scene as a teenager was coveted, adding that she and her group of friends were “extremely prominent in the party scene” and hosted get-togethers at various field houses and venue spaces.

“Riverdale, Dolton, Harvey, South Holland, Calumet City, anything that touched Sibley, essentially. We all grew up going to the same place,” Heard-Powell said. “You only had a handful of children-friendly party areas.”

Describing how her generation would also sneak into clubs, Heard-Powell shouted out Nitro, a popular nightclub in the western suburb of Stone Park, where older teens would congregate.

“By the time we was eighteen,” she said, “it was more fitting of you to go to a place like Nitro, because you couldn’t get an actual club.”

Nitro’s popularity intersected with the 1990s iteration of house music, known as juke music or ghetto house. A video posted on a Facebook page called Nitro Reunion pays homage to the venue and shows young Black club-goers in oversized T-shirts dancing to a house mix of DJ Unk’s 2006 record “Walk it Out.” The club, located at 3815 W. Lake Street in Stone Park, operated from 1997 to 2008. Today, that location is a strip club.

Many of those who spoke to The TRiiBE reminisced on the days of the parties when the dance form of juking was prominent. Similar to how teen clubs and school sets cultivated a space for house music and the jackin’ scene in the ’90s, juke also showed up in skating rinks throughout Chicago.

B. Kadijat Towolawi, thirty-seven, who grew up in Uptown, remembers the days at Rainbo Skating Rink in the North Side neighborhood. She also remembers news reports of an “investigation” into juke parties, which she believes led to the rink’s closure. Rainbo was demolished in 2003. The site is now a mixed-use housing complex named Rainbo Village, Condos & Townhomes.

“Parents were just enraged, enraged, because of what was happening at these parties,” Towolawi said. “Looking back as a fully grown adult, it got kind of crazy. It was basically almost dry-humping. [The news] was saying that girls are being sexually harassed. This is almost in comparison to a young version of Freaknik, that’s how they were trying to [portray it]. The parties were still going on, but it slowly started to die down. And that’s when it was also like a boom of the basement birthday parties.”

Other popular rinks that hosted both skates and jukes — often at the same time — are gone or trying to make a comeback. Markham Roller Rink shut its doors for renovations in 2022, according to the Markham Mayor’s office, and has not been open since. The South Side’s The Rink Fitness Factory skating rink is still operating, and its new owners are skate-centric and also shifting focus to health, even selling vegan foods inside.

Another popular teen hang back then was Fifth City. The East Garfield Park location became a popular destination for teens to congregate and show off their dance skills, including trendy Chicago dances like the percolator, footworking, and bobbing. Those same teens were often featured on the public access TV station CAN-TV channel 19.

Magan Marshall, thirty-seven, daughter of Gheri Marshall, said she remembers going to parties at Fifth City as early as eighth grade. It was where she met her “first fake boyfriend,” and enjoyed the vibes.

“My mom was very trusting, but of course, we always say it’s a different time, and we were able to have fun, but it felt good,” said the younger Marshall. “Even just hanging out on the street in our garages was a party to us.”

Heard-Powell credits youth culture’s embrace of drill music as the reason for the demise of the juke party.

“I hate to sound like an old lady, but I honestly feel like there were a couple of components that contributed to the downfall” of teen third spaces, she said. “The trend in music style, right? When we were young, it was no such thing as drill. We did have the gang bangers, and you know who the gang bangers were. That was a whole separate entity from the dance [guys].”

Heard-Powell believes lines got blurred between the gang and dance crowds, which led to dancing becoming uncool at functions. “With the drill era, it gradually changed the culture.”

Former Fifth Ward Alderwoman Leslie Hairston echoed the sentiments of Heard-Powell, though she also credits the commercialization of gun culture.

“Once the streets came into the party, it became something you couldn’t do financially,” she said, citing the risks of youth clubs.

Guns, gangs and their accompanying playlists did take over the city for a few years. The original, week-long Taste of Chicago was cancelled and remixed after a mass shooting. Once the tourists were endangered, policies had to change.

Sanders saw this shift in real time. She’s seen increased fear in the concept of Black youth congregating in public spaces, which she believes has led to the decline in third spaces.

People in general have a fear of young people, and you see that now some of it is justified when you see some of the violence and actions,” she said. “I don’t want stuff to pop off, because stuff pops off. Then there’s another part of me that thinks of my son. He goes to the beach just like I do, because he just wants to hang out and meet people, you know, like we all used to do.”

Magan Marshall agrees that today’s teens are criminalized for being themselves,

“Our parents let us go because they felt it was safe,” Marshall said. “They know that, ‘I can drop them off there,’ and then we gonna get picked up at 11:00. It was so much of a community aspect of it.”

Without a dedicated space to party, a hang out becomes a police problem.

“I’m from the West Side. Normally people say we loiter, but we like to hang,” Marshall said. “Hang out in the front. Hanging out in the middle of the street…We would be outside on somebody’s porch. When they see youth in numbers, then it’s automatically a problem, versus like, ‘Oh, they’re just, like, out enjoying themselves.’”

Sanders said she wants youth to be able to enjoy the city like she and her peers once did.

“You can’t go to the movies without bringing somebody — an adult — with you. So, where do you go?” she said. “We down these kids and say they don’t have any social skills. But, where [are] they gonna go where they’re not policed?”

Corli Jay is The TRiiBE’s community investment reporter.