This story was first published by MindSite News, a nonprofit news site that reports on mental health, and is the result of collaboration with Medill investigative Lab-Chicago. Sign up for the MindSite Daily newsletter here.

On a chilly afternoon in October 2023, a single mother stood in her living room on Chicago’s North Side as her teenage daughter erupted in rage, kicking, screaming and threatening to take her own life.

The mom, Pamela, was frozen, phone in hand, caught between a daughter having a mental health crisis and a system that previously had failed them.

A few years earlier, she says, her daughter had been outgoing. Good in school, she loved sports and had plenty of friends. But as an adolescent, her moods grew darker, her behavior volatile.

Amid her mental health struggles, Pamela—whose last name is being withheld to protect her daughter’s identity—was left grasping for support.

When she needed help for her daughter and called 911, police officers responded, and that usually left her daughter shaken. At times, she says, the police acted aggressively—raising their voices, getting too close, putting their hands on the girl, making things worse.

“When you have a dysregulated human, and you escalate, most often, that human will continue to escalate,” Pamela says. “Having the police come in and out of your house is very traumatizing.”

So this time when she called 911, she asked for the Crisis Assistance Response and Engagement or CARE team—a program created in 2021 to offer clinical help in a mental health crisis and limit police involvement. Within a few minutes, a van carrying a mental health professional, paramedic and police officer pulled up to Pamela’s home.

“When the CARE team came in, they were trained, and they knew how to calm the situation in a very professional, respectful way that my daughter was able to respond to,” Pamela says.

CARE became a lifeline, assisting her daughter, now nineteen, at least six times over the past four years and bringing stability to moments that once spiraled out of control.

But that, increasingly, is not the way the program is working. A six-month investigation by Medill Investigative Lab-Chicago and MindSite News found that CARE teams are responding to fewer and fewer mental health calls, that police are responding to the vast majority, and that the overall effort is hampered by dysfunction and bureaucratic infighting.

Operators answering 911 calls are dispatching CARE teams to mental health calls less frequently—a sign, former CARE staff members say, that dispatchers and first responders have lost confidence in the program.

Another hurdle looms, too: The federal COVID recovery funds that have paid for most of the program’s operations to date will run out next year. Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson said in a statement sent to Medill and MindSite News that he is committed to funding the program with city dollars and ultimately expanding it.

A movement emerges, and recedes

The use of mobile crisis teams to respond to mental health crises expanded nationally during the reform movement that intensified after a white Minneapolis police officer murdered George Floyd, a Black man, during an arrest. But today, many cities are struggling with increasingly uncertain funding and staffing shortages.

In Eugene, Oregon, CAHOOTS—the country’s most celebrated crisis response program—shut down this year. New York’s B-HEARD program has been mired in controversy, and responds to only a fraction of eligible calls. And federal budget cuts to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) are worrying operators of mobile crisis programs nationwide.

“I think everyone’s concerned right now,” Dr. Margie Balfour, chief clinical quality officer of Connections Health Solutions in Arizona, told Behavioral Health Business. “SAMHSA block grants fund a lot of this work. We’re definitely keeping our eye on that, but it’s hard to know what we’re facing just yet.”

What began as a bold experiment in public health is now at risk of becoming a cautionary tale.

A long time coming

In Chicago, calls to reform the mental health system long predated the launch of the CARE program. Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s decision to close six of twelve city mental health clinics in 2012 spurred citywide protests.

Advocates worried the closures would disproportionately affect underserved communities, many of whom relied on these clinics for mental health care and a sense of community. City officials said the clinics would be replaced with higher-quality private care through partnerships with more than sixty clinics, saving millions of dollars.

But vulnerable populations bore the brunt of the drop in access to care, increasing the likelihood that those suffering a mental health-related emergency would be met with police force rather than medical treatment, advocates say.

Indeed, as Medill and MindSite News previously reported, during almost the same period—August 2020 through August 2024—Chicago police used non-fatal force including taser, batons and non-fatal gunfire against more than 150 people following mental health-related calls to 911. Police also fatally shot one person in the midst of a mental health crisis, according to a Washington Post database. These encounters disproportionately affected Black people, who comprise 27 percent of the population but experienced two-thirds of the use-of-force incidents.

The push for reform accelerated in 2020. The Collaborative for Community Wellness—a coalition of mental health professionals, community-based organizations and residents—launched the “Treatment Not Trauma” campaign, demanding a citywide crisis-response system that didn’t rely on police and a plan to reopen the shuttered clinics.

Pushing for care, not punishment

In September 2020, Ald. Rossana Rodríguez Sánchez (33rd) introduced an ordinance calling for a move to non-police responses. The proposal, she later told Medill and MindSite News, reflected demands from Black and brown communities “that people experiencing mental health issues are met with care, not punishment.”

Opponents on the council and in the police union opposed the proposal as a move to “defund the police.”

CARE was then-Mayor Lori Lightfoot’s compromise: a two-year pilot involving teams of police officers, paramedics and mental health clinicians. Some activists opposed police involvement, but then-Police Supt. David Brown said officers would provide safety.

Including the police “was a really bad idea, and we fought against it,” says Arturo Carrillo, a founder of the Collaborative for Community Wellness and deputy director of health and violence prevention with the Brighton Park Neighborhood Council.

The CARE pilot launched in September 2021 with a $3.5 million budget, and its limitations were clear from the start. It operated in only a handful of neighborhoods between 10:30 a.m. and 4 p.m.—not what reform advocates had envisioned.

From the start, researchers at the University of Chicago’s Health Lab—which was commissioned to evaluate the pilot—saw serious challenges stemming from the need for police, fire and health department officials to collaborate. The agencies clashed over authority and approach, as well as seemingly mundane issues such as coordinating uniforms and meal breaks, said Jason Lerner, director of programs at the Health Lab.

Insiders agree, and say turf battles have hampered the program.

“There was a fight between the three entities” —police, fire and health—says one former CARE worker who spoke on condition of anonymity. “Who’s gonna be in charge? There was no real collaboration.”

That made it difficult to do the job effectively and made interdepartmental interactions feel “very quid pro quo—very ‘you do me a favor, I do you a favor,'” said former CARE clinician Patrick Cornelius.

“That was part of the learning curve for the city,” Lerner said. “People look at CARE and think, ‘Why isn’t it responding to more calls? Why isn’t it more widely available?’ But from my perspective, that’s the reason you have pilots.”

A mayor promises change

When Brandon Johnson took office in 2023, mental health reform was key to his agenda. He promised to reopen closed clinics, expand CARE’s hours and phase police out of CARE operations. Johnson has long been an outspoken advocate on the issue, having lost his brother to struggles with mental health.

Last September, Johnson’s office announced that CARE had transitioned to a non-police model and was being moved from the police department to the health department. He framed the change as a major step forward.

“By directing 911 mental health calls to public health teams, we are ending the criminalization of these issues,” the mayor said in a statement. “I am pleased that (police and firefighters) can transition back to their primary roles of protecting community safety and responding to medical emergencies.”

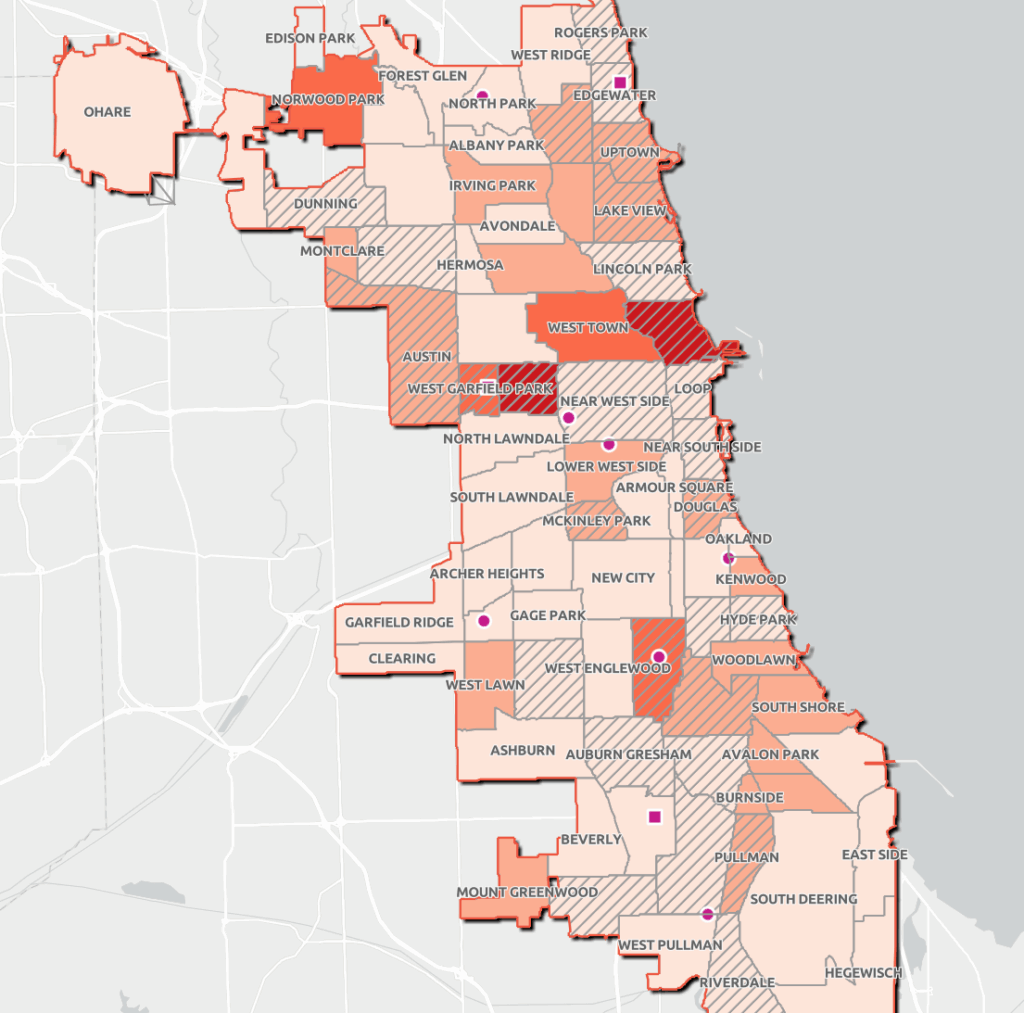

Today, seven CARE teams—composed of a mental health clinician and an emergency medical technician—respond to low-risk 911 calls involving mental health issues in specific police districts, mostly on the south and west sides, as well as Uptown, the Loop and several other North Side neighborhoods. One team can respond citywide.

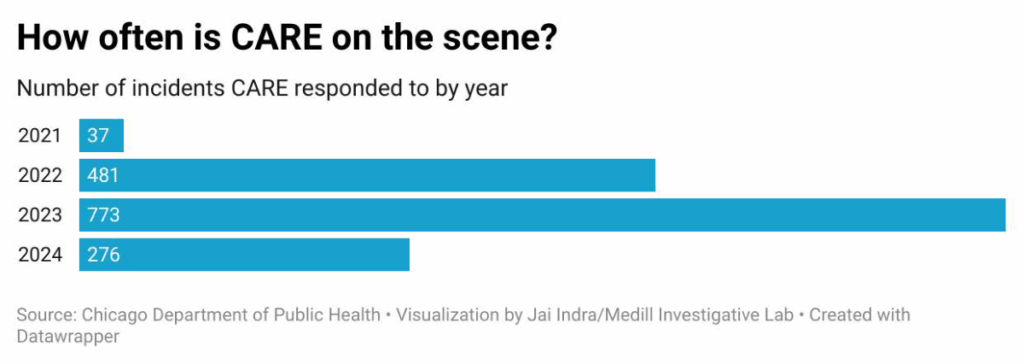

Health department call logs obtained by Medill and MindSite News show a slow rise and then an abrupt decline in the number of calls handled by CARE teams: They responded to 37 calls in 2021, 481 in 2022 and 773 in 2023. Then, amid Johnson’s 2024 restructuring, that number plummeted to 276.

This year, preliminary data show, CARE teams appear to be going on calls at roughly 2023 levels, but with a significant difference. When a CARE team responds, they are most often doing so after team members hear a radio call that police are already responding to.

Police are responding to the vast majority of calls designated in public records as CARE calls, mostly alone but sometimes alongside separate CARE clinical teams.

Since only the police can transport people to a hospital against their will, 911 operators often are reluctant to dispatch CARE teams. That frequently leaves CARE team clinicians sitting in their offices unsure what to do, a former staffer said. And since CARE vans operate without sirens, it takes them longer than police to get to a call.

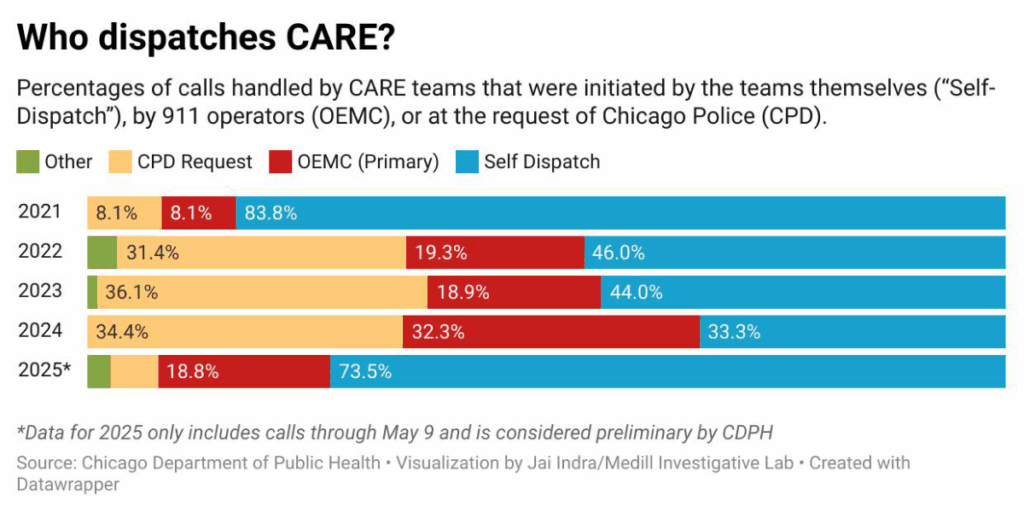

In 2021, only 8 percent of CARE responses were initiated by 911 dispatchers. That number rose to 19 percent in 2023 and 33 percent in 2024, according to health department data.

After the police were removed from CARE teams in October 2024, the portion of CARE responses initiated by 911 dispatchers fell from 46 percent in September to just 9 percent in December, while the portion of responses the CARE team initiated on its own rose from 29 percent to 86 percent.

The number of police calls for CARE assists also plummeted, from 62 percent of all CARE responses in August 2024 to just 5 percent in December 2024.

By another metric, CARE teams responded to fewer than 1 percent of 96,000 calls that 911 dispatchers categorized last year as potentially mental health-related.

The mayor’s office said in a statement to Medill and MindSite News that city officials are “aware” of these numbers and working to “develop solutions so that the CARE team is dispatched more frequently to meet the need for mental health services.”

The mayor is also appointing a committee to include his policy chief, Jung Yoon, and unnamed department heads, alders and community partners to develop an “action plan within the next 45 days“ to take corrective actions and address concerns.

Turf battles impede a program

In the program’s early days, the criteria for dispatching CARE changed frequently, said CARE clinician Drake Schoeppl, leaving dispatchers confused about which calls qualified.

“A lot of dispatchers were scared because they didn’t want to get in trouble” if a situation became violent, he says.

The health department wants 911 operators to deploy CARE teams more often, rather than the teams self-dispatching, says Dr. Jenny Hua, Chicago’s interim deputy commissioner for behavioral health, but it’s a hard call since dispatchers are supposed to be sure there’s no crime or medical emergency.

“We have investigated very, very, very, very, very thoroughly” why CARE is dispatched so infrequently, Hua says. In part, it results from having “a program that is meant to meet mental health needs sort of rubbing against the necessities of a 911 system that is designed to encounter emergencies.”

Hua says calls that have “nothing but a mental health component” and are clearly eligible for CARE are “a needle in a hay stack” of 911 calls.

The mayor’s office concurred. “The 911 system must assume the worst, because they don’t want emergencies missed,” its statement said. “A person could be lying on the street because of a heart attack, or an overdose, or a schizophrenic episode. In a medical emergency, a paramedic is the default first responder. In a violence-related call, police is the default.”

City records show CARE teams have responded to a wide range of settings with success.

In one case, CARE clinician Drake Schoeppl says, a woman barricaded inside her home because she thought the FBI was coming. Police surrounded the house for thirty minutes. When Schoeppl intervened, he listened without challenging her delusions.

“Cops a lot of times can get really impatient, don’t want to deal with it, or they don’t know how to deal with it,” he says.

Eventually, he says, she walked out on her own and agreed to go to a hospital for help—the kind of outcome CARE aims for.

In another case, in February 2023, a sixty-six-year-old woman was walking in traffic, incoherent and underdressed in freezing weather. CARE clinicians got her the hospital care she needed, records show.

About one-quarter of CARE calls in 2024 resulted in the person being taken to a hospital emergency department for evaluation.

Krista Murphy, a clinical social work lead in the psychiatry emergency department at Northwestern Memorial Hospital, says police officers or paramedics who bring people with mental health symptoms to the ER “aren’t able to really speak to their clinical symptoms just because they don’t have training in mental health.”

The mental health expertise of CARE workers, on the other hand, enables them to expedite assessments, allowing hospital staff to quickly determine whether psychiatric admission or alternative care is needed and benefiting patients, Murphy says.

The future of CARE

Since the CARE program launched in 2021, the American Rescue Plan Act has been its biggest source of funds—$6.87 million through this year. But that money will be mostly spent this year and must be fully spent by the end of next year, leaving a major gap in subsequent years.

Despite that challenge, Johnson “is committed to continued funding of the CARE program using city Corporate dollars,” his office said. “Even in a difficult budget year, CARE is a priority for the administration and Mayor Johnson will do everything in his power to expand resources for the program.”

His primary focus now, the statement said, is “effective implementation before we begin to plan for future expansion” that would grow the program’s geographic footprint and expand it to daily, round-the-clock operation.

Budget talks for fiscal year 2026 begin in August, and Rodríguez Sánchez is adamant that the city continue funding CARE. “To those who say CARE isn’t working: the truth is, we haven’t given it the full scope of resources or structure to thrive,” she says. “We can’t walk away.”

Pamela, the North Side mother, says CARE teams have helped de-escalate her daughter’s crises, connected the family with resources and helped them develop a plan.

“If CARE hadn’t come into our lives, I think things would have been much worse,” she says. “I think I would’ve been led down a different path, instead of focusing on her wellness.”

She worries what might happen if the CARE teams disappear or their roles become limited.

“I’m at the end of the road with this kid and the options available to her,” she says. “People with mental illness—they need help.”

Rachel Yoon, Janani Janarthanan, Tyler Williamson, Jai Indra, Nicole Johnson and Kari Lydersen contributed reporting.