Federal pandemic relief dollars that help pay for a Chicago program that sends clinicians instead of police to mental health crises are expiring, and under President Donald Trump’s administration, new funds for mental health and police alternatives seem unlikely.

Mayor Brandon Johnson has pledged to expand the Crisis Assistance Response & Engagement (CARE) program citywide; currently it serves only a limited number of neighborhoods. But the likely end of federal support means the city will need to find millions of dollars to sustain it—and even more to pay for the proposed expansion. A state program that provides funding for mental health crisis services is a potential source to help fill the gap.

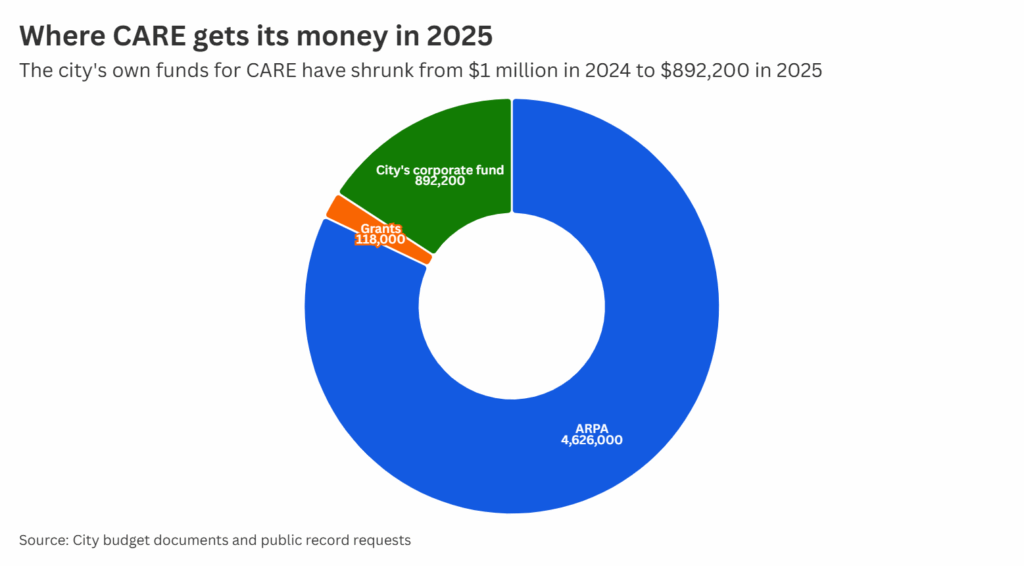

This year, more than 80 percent of CARE funding comes from the federal American Recovery Plan Act (ARPA), which provided COVID-19 pandemic relief, according to an analysis of budget documents by Medill and MindSite News.

“CARE is currently federally funded. And that funding is set to expire at the end of next year,” Dr. Jenny Hua, the medical director and deputy interim commissioner of behavioral health for the Chicago Department of Public Health (CDPH), told Medill and MindSite News.

She added that a reduction in federal funding creates “a terrible crisis for not just the health department but for all city agencies.”

The city used $4.46 million in ARPA funding for CARE employee salaries and pensions in 2025. Just $892,200 was devoted to CARE from the city’s corporate fund, the main pot of city revenue. An additional $118,000 was carried over from the previous year’s CARE budget.

So, millions in expiring pandemic funds will need to be replaced in coming years just to maintain CARE at its current level of service. In 2024, CARE responded to 239 calls, mostly in seven of the city’s twenty-two police districts, between the hours of 10:30 a.m. and 4 p.m.

There are currently fifteen police districts without CARE teams. Adding an additional team to each would cost about $9.75 million and expanding CARE service around the clock would cost about $7 million, according to the 19th Police District Council, an elected public safety body. 19th District Councilor Jennifer Schaffer said the figures are based on discussions with the mayor’s office.

The Mayor’s Office did not respond to questions about the cost of citywide expansion or other questions about the CARE budget.

In a statement to Medill and MindSite News, a spokesperson for Johnson said: “Mayor Johnson is fully committed to putting forward a budget that maintains funding for the CARE program and for mental health services generally. In his first two budgets, Mayor Johnson doubled the funding for CARE and, in spite of the serious fiscal challenges that the City is facing, Mayor Johnson plans to maintain funding for the CARE program while continuing to make reforms and adjustments so that the program can be successful and serve as many Chicagoans as possible within its current scope.”

Where the money goes

CARE was launched as a pilot program in 2021, and in the 2022, 2023, and 2024 budgets, the city allocated $1 million a year for the program.

An additional $6.87 million of ARPA money has also been budgeted for CARE since 2022. All pandemic relief money must be spent by 2026 or returned to the federal government.

Hua said that ARPA funds allocated for CARE will likely be used up this year and that in 2026, CARE would tap ARPA dollars that were originally allocated to another health department program for housing stabilization. According to the city’s ARPA dashboard, less than ten percent of the stabilization funds have been spent, leaving $4.87 million seemingly available for CARE.

The city’s Office of Budget Management did not respond to queries about such a reallocation.

CARE launched in 2021 as a joint program of the police, fire and public health departments under police administration. In September 2024, CARE was moved from the police department to the Department of Public Health and police officers were removed from the CARE teams. As part of the transition, the city reduced its reliance on contractors in favor of city employees, documents obtained by Medill show.

As of 2024, CARE had twenty-two full-time employees including crisis clinicians, community intervention specialists, and Emergency Medical Technicians (EMTs). Seventeen of them were assigned to the CARE team that year, with the bulk of their salaries paid with federal pandemic funds.

ARPA funds also paid for uniform allowances, office supplies, computer hardware, and communication devices.

In 2025, $500,000 in city funds were spent on paramedics who work with CARE clinicians and almost $300,000 was spent on gift cards used for Narcan, fentanyl test strips, and other supplies.

Demand for more CARE

On a Saturday afternoon in May, Patrick Lindley sat at the back of a small room in McFetridge Sports Center on Chicago’s Northwest side for a meeting of the 17th Police District Council.

The Albany Park neighborhood where Lindley resides is not part of CARE’s coverage area, but there’s plenty of need for CARE response. More than 700 calls were made to 911 for potential mental health emergencies in 2024 from the Albany Park community, according to city data.

“I don’t know how many of the folks that we have responding to 911 calls in our district are trauma-informed,” said Lindley, a community volunteer who would like CARE to extend to his neighborhood. “An ounce of prevention saves a pound of pain.”

Alderperson Rossanna Rodríguez Sánchez (33rd Ward) agreed.

“What we are missing is the commitment to funding that is going to allow us to expand this in a way that our communities need,” she told the group. “This saves lives, this saves us money.”

State funding potential

Could state funds provide the lifeline that CARE needs?

A 2021 law called the Community Emergency Services and Supports Act (CESSA) funds programs similar to CARE that sends mental health workers instead of cops. In 2024, the state awarded almost $70 million through CESSA to county public health departments, hospitals and non-profits, including some in Chicago.

A spokesperson for the Mayor’s Office said the city is looking to the 590 program as a source of funds for CARE, but the Illinois Department of Human Services (IDHS) told Medill and MindSite News that the program is not accepting new applicants for fiscal year 2026.

Hua said the health department is “in communication with the state to see if we’re eligible to apply and if the application is open.”

Clinicians or police?

Schaffer, a member of the 19th Police District Council, said while she and other CARE proponents are not seeking to “defund the police,” they believe that unfilled positions built into the city’s $1.8 billion police personnel budget could be used to help fund CARE.

In 2025, The TRiiBE reported that $170 million was budgeted for vacant police positions; advocates have called for those funds to be used for youth and public health programs. As of April, the department had vacancies for 142 police officers, seventy-seven field training officers, and fifty-five sergeants, according to the Chicago Public Data Portal.

Expanding CARE would take mental health crises off the police department’s plate, freeing officers to do the work they are trained for, Schaffer said.

Budget discussions that began this month will help determine CARE’s future. Rodríguez-Sánchez, Schaffer, and other leaders are urging the mayor and City Council to keep it going.

“If they don’t find a way to fund it, it’s going to go away,” Schaffer said. “It is the mayor’s job to hear what the community wants and figure out how to get it funded.”

Janani Jana is an international journalist with multimedia experience in business, government policy, and data reporting. She’s a graduate of the investigative masters program from Medill School of Journalism, Northwestern University.

Nicole Jeanine Johnson is an investigative journalist from Chicago, IL. She’s a graduate of the investigative masters program from Medill School of Journalism, Northwestern University.