Lack of enthusiasm from the fire department was among the troubles plaguing the CARE (Crisis Assistance and Response Engagement) program. Documents and interviews with former CARE staff reveal that CARE teams could often not be deployed to mental health emergencies because fire department paramedics who were part of the teams were unavailable.

But when the city decided to remove fire department paramedics from CARE and replace them with new emergency medical technicians (EMTs), the union representing firefighters fought back with an unfair labor practice charge and a grievance.

Union officials say the city’s decision to replace fire department paramedics with EMTs means CARE teams are less prepared to deal with medical emergencies, reducing the number of calls that CARE can handle. The city argued that EMTs are equipped for the work that CARE does, and as CARE is a relatively new program, the fire union has no contractual right to the work.

In June, an official arbitrator decided against Chicago Fire Fighters Union Local 2 and in favor of the city in the dispute.

Union president Pat Cleary said the union is dropping the fight for now, as “we’re hearing from the city that they’re going to disband the whole program, so we’re not going to waste our time.”

But Mayor Brandon Johnson’s office told Medill and MindSite News that the city plans to fully fund CARE, with budget discussions ongoing for the next fiscal year. And Cleary said that if CARE does continue, the union will “one hundred percent” revive its fight to include fire department paramedics on the teams.

An unpleasant surprise

Modeled after similar initiatives nationwide, the CARE pilot launched in 2021 deployed eight Chicago Fire Department community paramedics, more than twenty police officers with training in crisis intervention, and about half a dozen mental health professionals working for the public health department to neighborhoods with high rates of mental health-related 911 calls and emergency transports.

The fire department had trouble finding enough paramedics who wanted to work with CARE, according to a June 9 report by arbitrator Peter Meyers. Difficulty filling the eight slots for fire paramedics meant that CARE vans sometimes weren’t deployed. Meyers found that seventy to eighty fire department employees were eligible to take an extra training to work with CARE, but only four responded to the department’s multiple requests for volunteers, and two were ineligible while one was already assigned to CARE. However the University of Chicago Health Lab was contracted to do an evaluation of CARE, and noted that the fire department and police department were “enthusiastic partners” who contributed to the program’s success.

The fire department paramedics on CARE teams would conduct a brief medical assessment of the patient, taking vital signs to ensure they were not experiencing a medical emergency. If they were, the team called for a fire department ambulance; if not, the CARE team completed an assessment and determined where to transport the patient.

Fire department paramedics were still “riding on the CARE vans,” which the department donated to the program, when the union was notified on April 11, 2024, that the city had posted a job opening to hire EMT-Bs—a lower classification than the fire department paramedics—for the same vans.

Anthony Snyder, the firefighter union’s director of emergency medical services, says the EMT job posting came as a surprise, sowing anxiety and resentment. Less than two weeks later, the union filed the grievance and unfair labor practice charge.

A difference in training and capacity

Snyder emphasized that the fire department has “strict hiring guidelines” and only employs people qualified as EMT-Paramedics. When the fire department was removed from CARE, EMTs without the paramedic qualification—EMT-Bs—were hired in their stead.

Nationwide EMTs make a median annual wage of $43,000, according to 2023 data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The EMTs working for CARE currently start at $46,516 per year, according to public records obtained by Medill, whereas union fire department paramedics earn over $62,000 a year, according to a city website.

Victor Chan, a co-owner and instructor at the company Chicago EMT Training, said, “You have the expectation [as a paramedic] of being the highest level of care when someone calls 911.” He explained that paramedics train for around a year, compared to three to five months for an EMT-B, or Emergency Medical Technician-Basic.

The two primary levels of EMT certification are EMT-Basic (EMT-B) and EMT-Paramedic (EMT-P). Often, EMT-Ps are just referred to as paramedics.

Chan said paramedic training “feels like a full-time job. You’re doing many more clinical rotations; you’re rotating through every ICU and many other rotations through various hospitals.” With that understanding, he said, the amount of medications that EMT-Ps work with “exponentially expands” from the approximately dozen that EMT-Bs are trained on.

EMT-Ps are also trained to use cardiac monitors, apply electrocardiograms (EKGs), and interpret heart rhythms to assess potential cardiac issues. In contrast, EMT-Bs are trained to use automatic external defibrillators during cardiac arrest, according to Chan.

Daniel Cronin, a doctor and professor at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine who is also a licensed paramedic, noted that paramedics in Chicago operate under physician oversight, which allows them to perform a wide range of medical interventions, as long as they follow standing orders.

“If I witness a psychiatric emergency, there are certain standards where an EMT-B would never be on scene for something like that. Two paramedics will be on scene for that, and then we can escalate. They would never put an EMT-B in that type of situation; they would call somebody else to be there,” Cronin said.

He added that EMT-Bs are typically used for lower-risk transfers, such as bringing someone home from the hospital or helping them up the stairs. EMT-Bs operate under basic standing orders and can perform CPR if someone is unconscious; however, they cannot “run a code,” meaning they cannot give directives or manage a cardiac arrest situation independently, according to Cronin.

“They don’t carry any drugs, they’re not trained on a cardiac monitor, things like that,” said Snyder. “And the labor rate that they’re offering was less than half what they’re paying a paramedic.”

One CARE EMT who replaced a fire paramedic, Kameron Younger, was hired on September 4, 2024. In January, Younger was charged with one misdemeanor count of possessing ammunition without a valid license. Younger was no longer employed by CARE as of spring 2025.

In March 2022, when Younger was a candidate to join the fire department, he threatened to shoot up the Fire Academy—a full-time, six-month training program for paramedics and firefighters.

“They were giving our work to other people, and the people they hired were people with bad histories,” Cleary said, then referenced Younger. “One guy was thrown out of our Fire Academy for having mental issues. He was one of the guys they hired. I’m like, ‘You’re sending this guy on mental health runs? He has his own issues.’ It’s pretty hard to get kicked out of the Academy.”

As of January 2025, the CARE program employed nine EMTs, according to a staff roster obtained by a public records request. Two had left in 2024, including Younger.

According to a City of Chicago posting for the role, EMTs are expected to “perform patient care medical assessments to persons experiencing a crisis or problem related to unmet mental health, substance use, physical health, or social service needs.” The only listed requirement is “basic emergency and prehospital care training acquired through EMT training.”

Applicants must be certified EMTs; however, the posting does not specify the level or extent of experience required.

“This is really a question of medical care, and I know that the CARE team primarily goes to mental health emergencies,” said Snyder. “But many times, differentiating between what is a mental health emergency and what is really just a medical emergency that manifests itself with altered mental status, sometimes, it’s hard to tell. We think the best person to do that is a paramedic.”

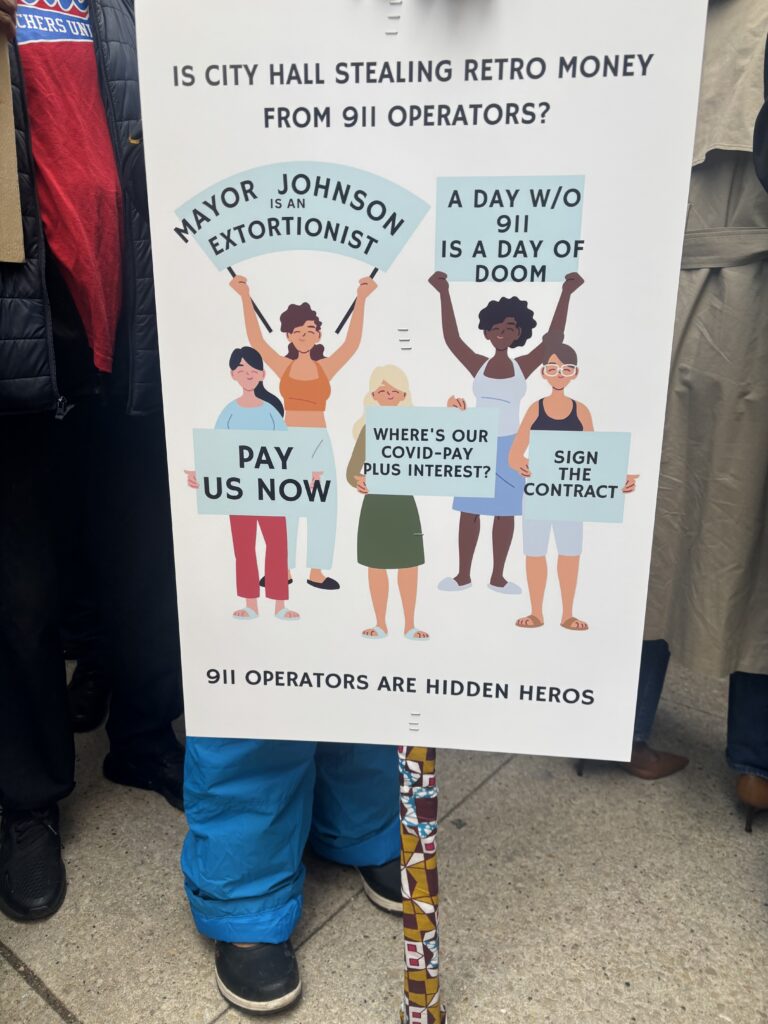

Union battles

The fire union’s complaint alleges that the city made a unilateral change to a mandatory subject of bargaining—namely, substituting EMTs for fire paramedics on CARE teams—without first negotiating either the decision or its effects.

“The process in which you go to the board and you file a complaint; you’re actually accusing the other party of breaking the law,” said Professor Robert Bruno, who runs the Labor Education Program at the University of Illinois, Chicago. “The firefighters are making the case that this is work that’s covered under the collective bargaining agreement. It can’t be outsourced, and therefore it’s a violation of the agreement.”

In November, the Illinois Labor Relations Board referred the unfair labor practice to an impartial arbitrator, and then dropped the charge once the arbitrator ruled in favor of the city.

The ruling noted that: “The evidence indicates that the actual work that the paramedics on the CARE Teams were performing amounted only to very basic assessments to ensure medical stability or determine whether a Fire Department ambulance should transport the client”—so highly-trained paramedics were not necessary.

The arbitrator emphasized the fire department’s failure to recruit enough of their own paramedics to participate in CARE, and noted that “the city maintains that the effectiveness of alternate response programs is important in public safety reform, but the CARE Program cannot be effective if the city struggles to appropriately staff it.”

The CARE dispute comes amid broader contract tensions between the city and the firefighters union. The firefighters’ collective bargaining agreement expired on June 30, 2021, and the parties spent months in arbitration to resolve the deadlock. A tentative deal was reached this month, which still needs to be approved by the union and City Council.

Cleary recently told Medill and MindSite News that CARE is not a priority at the moment, since the union is in a high-stakes fight over its contract. But he is adamant that any crisis response program must involve the fire department. He noted that New York City’s B-HEARD program includes union fire department paramedics.

“They’re part of the firefighters union in New York,” Cleary said. “Why wouldn’t this group (CARE responders) be part of the firefighters union?”

Charlotte Ehrlich is a journalist and editor based in New York City. She’s an undergraduate of Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism.