Welcome to our home—the sweet family,” read the cheerful wall decal, visible through the South Shore apartment’s front doorway. The door was wide open, its deadbolt destroyed by a federal agent’s battering ram a week before.

The apartment, one of dozens targeted by federal immigration agents in a September 30 midnight raid on the entire building, was empty. Workers from the building’s management company had removed the furniture as well as most signs these rooms had recently been home to a family.

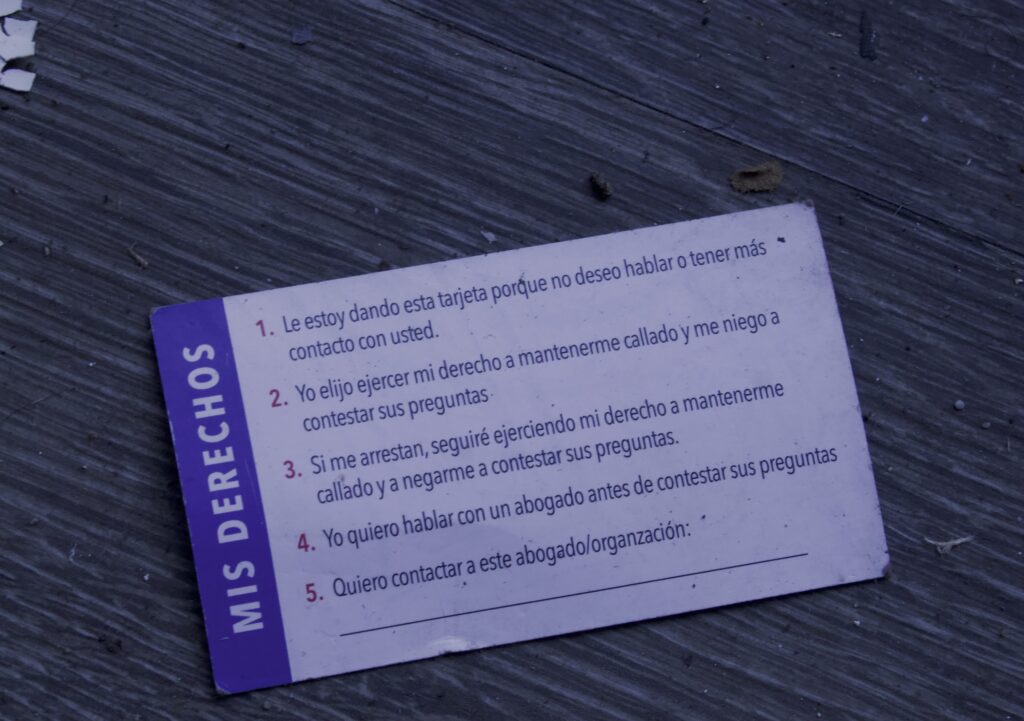

But in the kitchen cupboards, a few bags of beans, a package of quick oats, another of flour, and a can of pears sat on the shelves. In the fridge, avocados and ears of corn were beginning to spoil. On the kitchen floor, a know-your-rights card in English and Spanish offered advice on what to do if confronted by immigration agents.

Sunlight slanted through the living-room windows, illuminating floorboards recently dirtied by work boots. On the floor, a broken fidget spinner, a ball, and a red matchbox car gave testament that a child had lived here. The child played here, slept here, and was startled awake with their parents when agents began battering the front door.

The bedroom door stood ajar, decorated with a few pink stars around another cheery decal. The stars were arrayed with a few other stickers—an ice cream cone, a flower, a tiny pineapple—with a randomness that suggested the child had placed them there.

Who slept in this room? The child who played in the living room? The “sweet” family, cozy, all together? Perhaps this apartment was their first small bit of refuge after walking thousands of miles to America, getting bussed to Chicago, sleeping on police station floors and in crowded shelters, before finally finding a place to call their home. A cramped, shabby two-room apartment. But a home.

The family is gone. The people taken in the raid never showed up to their jobs that morning, leaving coworkers to wonder. The child, if they attended the school across the street, was absent. Someone’s student, someone’s classmate, someone’s child’s new best friend, is gone. Did their schoolmates wonder for a day or two before the realization sunk in?

Whatever community the family had begun to find in the building was shattered by the raid. Many of the other apartments, their doors battered down, were boarded up. The few residents still living in the building weren’t eager to stay. At the end of one hallway, a visitor had a hushed conversation at a woman’s door. “I’m leaving,” she said.

Outside, an older man sat in a pickup truck, its bed full of assorted belongings. Was he the building super? “No,” he said. “I’m helping someone move out.”

The SUV was askew, blocking most of one lane of a busy intersection in Lincoln Square on the morning of October 10. Its rear bumper hung off, taillight obliterated. Minutes earlier, masked Border Patrol agents who’d taken several people into custody near the intersection had rammed the SUV as they made their getaway. Among those abducted was Debbie Brockman, a producer for a local TV station who’d been waiting for the bus on her morning commute when agents pulled up.

Visibly shaken, the couple that had been in the SUV stood on the sidewalk, talking to a police officer. The night before, they’d been at Wrigley Field for a Cubs playoff game. Now, their morning upended, they were considering the potential risks of filing a police report about a car crash perpetrated by federal agents.

A few neighbors who’d filmed the abduction and crash stood near the couple, angry at what had just unfolded. A tow truck driver, waiting for the police to finish taking their report, collected a few shards of the taillight and stacked them gingerly on the curb. “They said they was just gonna take criminals, bad people,” he said quietly. “But they’re acting like animals.”

After the police left, the neighbors who stuck around spoke to reporters, eager to share their videos and denounce the agents’ behavior. After an hour or two, they parted ways, called by the demands of work and daily life. Aside from the detritus of the crash, nothing indicated the terror and chaos that had briefly gripped the site that morning.

Hours later as the sun began to set, a lone woman stood on the corner, holding a tall black candle. Her face was obscured by the hood of a forest-green cloak. Three more candles sat on the curb before her, a few feet from where the SUV had been that morning.

Alone and anonymous, she kept a vigil in the gathering darkness. “I’m here for Debbie,” she said.

Autumn’s early dusk had fallen on the Rogers Park church before the evening service let out, and a warm glow emanated from within. A sign on the church wall advertising the daily Mass schedule was covered with a black cloth because earlier that day, October 12, immigration agents had been spotted nearby. After that morning’s Mass concluded, parishioners, warned of the threat, had been reluctant to leave the church. Neighbors had volunteered to escort them to their cars.

During the day, word of the sighting had spread through networks on social media and cell-phone threads. Now, a yard sign detailing one’s legal rights when talking to agents was prominently displayed at the end of the block. On the sidewalk, someone had chalked instructions for reporting sightings of agents to the Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights (ICIRR), and added: “We keep us safe.”

Inside the church, the few people in attendance approached the altar to receive Holy Communion. When Mass concluded, they slipped out the door one by one. Later that week, the church’s pastor would be heading to Rome, possibly to have an audience with the Pope. Would he tell the Chicago-born pontiff what had unfolded in his hometown that day? The priest didn’t say.

Outside, in a scene that’s been repeated in neighborhoods across Chicago in recent weeks, another kind of communion was taking shape.

Up and down the block, small groups of people stood and talked to one another. Most had never met before. Many wore whistles around their necks to warn the neighborhood in case agents were spotted. A few stayed near the church steps, watching in all directions, while others walked off to patrol the surrounding streets. In the wake of the agents’ violence, they were building community and loving their neighbors.

“It’s really heartening to know that there’s people out there that’ll catch you if you’re falling,” said a neighbor named Julie who was among those keeping watch. That morning, she’d shouted at immigration agents from her apartment window; now, she was plugged into neighborhood text-message trees and social media groups. “And we’ve got to look out for each other.”

Jim Daley is the Weekly’s investigations editor.