Jeanne Bishop believes her profession is a vocation. After her pregnant sister and her brother-in-law were killed, she wrote a book about her path to forgiving her family’s murderer. Then she became a public defender in Cook County, representing those charged with lesser or even similar crimes.

Of all the legal professions, the public defender is the underdog, pitted against prosecutors armed with more money and manpower. Being a public defender can be a thankless job, met with an all-too-common refrain: How can you defend these people?

Nevertheless, many are driven by a fierce moral imperative: to fight for those exiled to society’s margins. Yet quiet wars waged in courtrooms can become attritional, leading to compromise. Often, public defenders meet with their clients when they are already detained in a place infamous for its controlled chaos: the Cook County Jail, one of the most overcrowded jails in the United States.

As the months, or even years, drag on before the trial even begins, Bishop says defendants become anxious, stuck in an echo chamber with other prisoners.

“People who have never been locked up before don’t realize what an enclosed environment that is. You are locked away from your friends and family. Some people can’t afford to visit,” says Bishop.

The time defendants spend in the Cook County Jail takes its toll. “They’ll plead guilty sometimes to get out. I tell people, ‘Please don’t do that,’ and they’ll say, ‘Ms. Bishop, I can’t stay here one more day.’ ”

If a defendant cannot afford to hire their own attorney, the government is obligated by the constitution to provide them with one. In this sense, public defenders are often the only resource for those accused of crimes. Their ability to protect their clients is undermined, however, when the infrastructure of the criminal justice system gets in their way.

Toni Preckwinkle, the Cook County Board President, outlined an ambitious criminal justice reform agenda in March, calling for the end of mandatory prison sentences for nonviolent offenses and for the creation of better juvenile justice laws.

However, few have explored the role that reforming public defense can play in the larger criminal justice reform conversation. Even less attention has been paid to how mass incarceration helped create the crisis the public defense profession faces today. If public defense continues to be devalued, in Cook County and elsewhere, this will maintain an unequal balance of justice that harms poor defendants—those who have the most to lose from the consequences of a drained public defense system.

PUBLIC DEFENSE IN COOK COUNTY

More than half of all criminal defendants in Cook County are represented by a public defender. That’s no small number. In its statistical reports, the Administrative Office of the Illinois Courts found that the Cook County courts saw a significant drop in misdemeanor and felony case filings from 2009 to 2014. However, there has been a 162 percent increase in the county’s incarceration rate since 1978, according to the Incarceration Trends Project, an analytical tool created by the Vera Institute of Justice to track incarceration rates in jails across the U.S. Because of how many people the county incarcerates, the public defender office manages more than a hundred thousand cases each year—and that’s a conservative estimate.

“I know we are severely strained for clients,” Bishop says. “You hear all the time, ‘You don’t see rich people on death row.’ Our resources are limited from the county. Even though every year the head of our office asks for money, we have to work within the resources that we do have. So it’s a constant challenge.”

The significant burdens on public defenders raise questions about whether they can be as effective as private lawyers, or work through all their cases without undue delays. Those burdens also make it harder for them to protect defendants from court fees and assessments that can push low-income clients into a cycle of debt. In Cook County, some misdemeanors can carry a fine of $2,500 or more, and certain drug convictions can result in fines of more than $500,000. And it’s not just convictions: multiple smaller court costs can also create an inescapable fiscal burden for defendants living in poverty.

“The pressure of too many defendants and too few resources has subtle but important effects on communities,” reported the Illinois State Bar Association in its 2013 publication on the funding crisis in the Illinois courts. “Delays in resolving cases leave victims, witnesses, and even whole communities with no sense of closure, and leave those who are wrongly accused with a diminished sense of vindication. In the criminal system more so than in other parts of the court system, justice delayed can truly be justice denied.”

A PUBLIC DEFENSE CRISIS?

Illinois is hardly the only state facing this problem. The national narrative of public defense is one of crisis: resource deficiencies, funding instabilities, and crushing caseloads are endemic to public defense offices across the country, leaving some hopelessly crippled. In Missouri, the state’s top public defender responded to persistent funding shortages by unsuccessfully attempting to order the governor, a lawyer who more than once has blocked increased funding for the office, to defend an indigent person. Meanwhile, in Louisiana, the New Orleans public defender’s office has joined the host of public defense systems sued by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU)—in their case, for refusing to represent more clients.

Some public defender’s offices are stronger, such as the one in the Bronx in New York City, which uses a holistic defense model incorporating social services, and in San Francisco, where residents elect the chief public defender. But they are exceptions.

Where do Cook County public defenders fall on the crisis spectrum? Though Cook County’s public defense system is not in such dire straits as those in, say, Missouri, it is still affected by the same obstacles of insufficient finances and unreasonable workloads. But even if the diagnosis isn’t fatal, the disease shouldn’t be ignored.

The public defense budget endures waves of volatility. Funding models for public defense vary state by state, and Illinois has a county-based public defender funding model. Counties that exceed the threshold of 35,000 citizens are legally required to establish and fund their own offices. Last week, Preckwinkle released the fiscal year 2017 budget recommendations for Cook County; they would cut eighteen staff positions from the public defender’s office, says Lester Finkle, the Cook County Public Defender’s Office Chief of Staff.

Preckwinkle’s proposal includes slight increases in appropriations for public defenders, but these are to pay for employee benefits like health insurance, which were not previously included in departmental budgets. But, Finkle notes, the recommended budget is funded in part by revenue from a proposed tax on sugary drinks. If no such additional revenue is generated, there could be as many as a thousand positions cut in not only the public defender’s office, but also the sheriff’s department and the state’s attorney’s office. Preckwinkle’s smaller cuts, then, are dependent on an unsecured source of funding.

Even though Cook County has one of the largest public defender systems in the country, with twelve divisions and over 500 attorneys, a constellation of failed criminal justice policies, including high arrest and incarceration rates, pre-trial detention, and poor jail conditions, directly impact the work of the public defenders. The more people who are incarcerated, the more lawyers there must be on hand to defend them.

As a result of these difficulties, usually all a public defender can accomplish is mitigation, or the negotiation of sentence reductions. Often it’s a form of damage control.

“Our job all the time is to prevent our clients from going into custody, or if they are in custody, to get them out,” Bishop says. “We file motions to reduce bail. We file motions to get our clients on electronic home monitoring while they’re waiting for their case to be resolved.”

But public defense has been largely left out of the national conversation on criminal justice reform.

Jonathan Rapping, founder of Gideon’s Promise, an Atlanta-based nonprofit dedicated to training public defenders, says this is a fatal flaw.

“As someone who has been devoted to public defense reform my entire career, I am excited that finally, as a nation, we are talking about criminal justice reform,” says Rapping. But you can watch countless panels and presentations and read countless articles [on criminal justice reform], and there will be forums put on about it, and we talk about sentencing reform and decriminalizing certain behaviors, but the words ‘public defender’ will never be mentioned once. The Democratic Party’s platform finally addressed criminal justice but never mentioned public defenders.”

THE IMPACT OF MASS INCARCERATION

Mass incarceration has not only made the United States the country with the largest prison population, both in total and per capita; it has also dealt an enormous blow to public defense. (Some scholars also argue that the opposite is true, that a weakened public defender system makes mass incarceration worse.) In the 1970s, a perfect storm of enforcement mandates spiked the number of arrests for drug crimes. These cases added to the workloads of public defenders, less than twenty years after Gideon v. Wainwright, the landmark 1963 Supreme Court decision that ruled that the states were constitutionally obligated to provide lawyers for criminal defendants who could not afford to hire one on their own.

“Our criminal justice system has grown dramatically since 1963—without the funding necessary for public defenders to keep up with growing caseloads and resource demands,” reported the Brennan Center for Justice in “Gideon at 50.”

Keith Ahmad, the assistant public defender under the head of the Cook County public defender’s office, Amy Campanelli, says that the sheer number of defendants public defenders must represent has a direct impact on case outcomes. He has been a public defender for more than twenty-eight years.

“The longer it takes for us to represent a single client, the longer Cook County jail has to house that person. What directly impacts how long it takes us to represent those clients is the number of clients there are per attorney,” Ahmad says. The fewer public defenders there are, the more clients each defender has, and the more a defender must jump back and forth between different cases, making it difficult to resolve each case in a timely manner. The Guardian has reported that the overuse of continuances by public defenders, or postponement of trial in order to buy more time to prepare, creates trial delays that force poor clients to stay in jail longer.

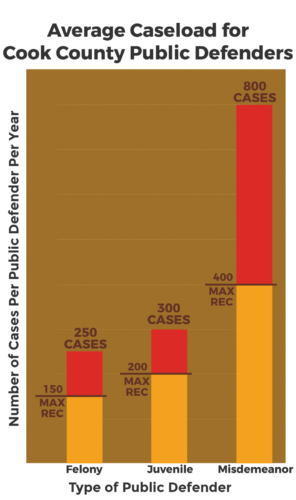

The average caseload burden for a public defender in the felony, misdemeanor and juvenile divisions is astronomical. According to Finkle, the average caseloads for felony attorneys are approximately 250 cases per year; for misdemeanor attorneys it’s more than double, at 750 to 800 cases per year; and the attorneys in the juvenile justice division manage around 300 juvenile delinquency cases a year.

These numbers far surpass American Bar Association’s national guidelines for reasonable workloads (150 cases per year for felony attorneys, 400 for misdemeanors, and 200 for juvenile justice), even though the office has seen slight increases in appropriations over the last five years.

This overwork can be exacerbated by flawed criminal justice practices, such as detaining those who aren’t convicted of crimes. Pre-trial detention, the policy of detaining those who cannot pay bail, has led to what is lamented as an “assembly line” for justice; it’s a key reason why the Cook County jail is so overpopulated. Bond court at 26th and California sees a revolving door of defendants every day. It’s where public defenders meet with their clients for the first time, and this interaction usually lasts less than two minutes before the hearings. The brevity is a result of public defenders’ huge caseloads, which limit the amount of time, preparation and investment they can devote to each case.

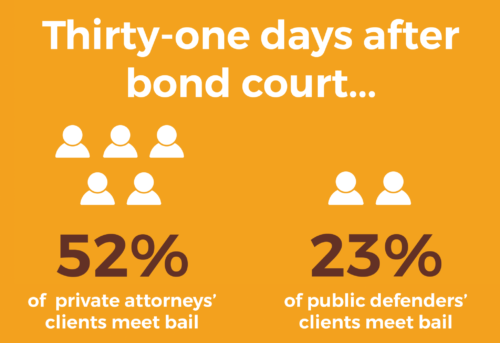

Even when public defenders are spending time representing a client, studies indicate that there is an asymmetry in the courtroom that puts them at a disadvantage. In July, the Cook County Sheriff’s Justice Institute (SJI) released an analysis of felony bond court based on a review of 1,574 cases from February 1 to March 29 of this year. The SJI found that private attorneys were given 300 seconds on average to speak on the behalf of their clients, but public defenders were only given one hundred seconds. The SJI also found that within thirty-one days of appearing in bond court, fifty-two percent of private attorneys’ clients bailed out compared to twenty-three percent of public defenders’ clients. It’s evident that the odds are stacked against both public defenders and their clients.

SHORTCOMINGS OF PUBLIC DEFENSE

It’s also no secret that choruses of complaints have been levied against public defenders. In the context of the obstacles public defenders face, it can be difficult for clients to feel they have been represented fairly.

One such former client is Colette Payne. A local TV news anchor once asked Payne why she broke the law if she loved her two young sons. Payne, now forty-nine, said the question made her head spin. It’s a reminder that the past can never truly leave you.

As a teenager, Payne’s life was far from easy. She came of age in the 1990s and lived in the Ida B. Wells housing complex during the heyday of the city’s public housing projects. Her mother was a secretary, and her father owned a dance studio. She had two sisters and three brothers. Her older sister suffered from mental illness, which was swept under the rug, she says. When her father got sick, her family fell on financial hardship and ended up losing their home. That’s when she started to steal. Later, she would battle a drug addiction.

From the 1990s to 2012, Payne was incarcerated five times. For one of those convictions, she was represented by a public defender. Payne felt let down by her legal counsel.

“I felt at the time that the public defender was not on my side. I feel that they didn’t have my best interest at hand,” she says.

“They would say things like, “ ‘Well, you have a background.’ I would say, ‘I need help, I’m addicted.’ And they’d say, ‘Okay, whatever.’ But you know, you’re facing anywhere from two to ten [years] because of your background. It wasn’t like they were really trying to help me get out of the situation.”

Her story mirrors the frustrations felt by others in similar situations: their doubts and fears can fall on seemingly unsympathetic ears, and there’s a loss of trust. In at least one case, tensions between a public defender and a client reached a boiling point. In 2001, the ACLU filed a class action lawsuit on behalf of Anthony Jefferson, who at the time was incarcerated at the Menard Correctional Center serving a seventy-five-year sentence, after the Cook County public defender assigned to his appeal filed an Anders motion, which dismisses an appeal on the grounds that it is frivolous. The ACLU’s lawsuit argued that the office refused the case unfairly and alleged the office routinely filed such motions on appeals that were not frivolous solely to clean out the office’s mounting backlog of cases. After several months, then-governor George Ryan approved a $4.7 million budget to have the state appellate court take on a large portion of the appeals cases.

Some of the frustrations voiced by Payne, however, point to how public defenders are only able to assist their clients with the legal process, not the factors that got them there.

“We believe there is an important purpose to the criminal justice system, especially if there are crimes of violence and crimes where there are victims. But there are a lot of victimless crimes that can be treated other ways,” says Aisha Edwards, the supervising criminal defense attorney at Cabrini Green Legal Aid, a legal service offered in the city that specializes in criminal and housing cases. It is the only no-cost legal service for adult criminal defendants in Chicago other than the public defender’s office. Edwards transitioned into criminal defense practice after eight years as a state prosecutor.

Edwards believes public defenders and other attorneys representing low-income clients face a mountain of difficulties.

“I think public defenders and us who work on behalf of those who are indigent do the best with what we have. The reform starts with the types of laws we have on the books,” she says. “Even as a prosecutor, there’s a lot of cases in the system where they are just not the best use of judicial resources and taxpayer money. There’s so many nonviolent cases. There are so many misunderstandings. There’s a lot of cases where there aren’t any crimes being committed until law enforcement happened upon the scene.”

Edwards also meditates on what the short-term gains are for incarcerating a person for a minor offense versus the long-term way a rap sheet can disrupt a person’s life.

“Should this one case go on and prevent them from living a productive life, and have a job and contribute to society?” Edwards asks. “Especially if they are really young?”

WHAT DOES PUBLIC DEFENSE NEED?

In the public defense crisis, the stakes for the indigent are high. Their fate rests in the hands of these lawyers, who, by and large, recognize the collateral damage of the criminal justice system, from the harsh conditions of its facilities to the lifelong burden of a criminal record. If public defenders can’t win an alternative to holding a defendant in custody, or if they lose a case, it harms clients’ immediate present (loss of work, strain on family bonds), and it can hurt their chances for a second act.

Resolving financial and resource deficiencies is only a start. Caseload caps—and the funding required to continue representing all clients while still enforcing them—can alleviate workloads. But increasing resources won’t fix the underlying problems that cause such strain on the system, as the chief Cook County public defender Amy Campanelli recognizes. She told Chicago magazine in February that “it’s all about poverty.” It’s necessary to shift the focus to addressing the structural social problems faced by residents in impoverished neighborhoods that catapult them into the justice system in the first place.

Rehabilitating defendants and healing divides with those they’ve harmed is at the heart of the concept of restorative justice, and in Chicago, the restorative justice movement has gained some traction: the first community court was established in North Lawndale last April. Still, right now, the allocation of these services is limited; there’s not enough for everyone who may need them. Diversion programs, like mental health and drug courts that provide treatment options to clients instead of incarceration, are also limited in the number of participants they can accept, and strict requirements must be met by those accepted into these programs.

But the reality is that as long as we maintain the basic framework of criminal justice, people will always get arrested, and people will always go to jail. For Malcolm Rich, executive director of the Chicago Appleseed Fund for Justice and the Chicago Council of Lawyers, empowering public defenders means low-income defendants have better access to justice. And because the majority of low-income criminal defendants are people of color, the issue of public defense becomes one of racial justice too.

“A strong public defender system is essential to provide the check[s] and balance[s] necessary within the criminal justice system; protecting…individual rights but also protecting the integrity of the system,” he says. “For example, a public defender can challenge an unfair bail ruling, thereby reducing overincarceration. A public defender can challenge unfair imposition of court costs, fines, and fees—protecting against these ‘taxes’ which destroy lives and communities. Public defenders safeguard our criminal justice system.”

The conversation about criminal justice reform, on a national and local level, would benefit from recognizing how failed criminal justice policies feed into the obstacles public defenders face. If public defenders were consistently given sufficient money and resources, they could invest more time into advocating for their clients, which would result in fewer people incarcerated, and ensure that those who are convicted are sentenced more fairly. If bond reform measures were implemented, such as releasing more people under electronic monitoring, fewer people would be held in custody before their trials begin, and relations between public defenders and their clients could dramatically improve. Reforming mandatory minimum sentencing and moving toward jail diversion programs would alleviate the pressures both public defenders and clients face to accept unfair sentences and would instead put the focus on the client’s treatment and rehabilitation. In a system that empowered and supported public defense, it would be easier for public defenders to use the law as a shield for low-income defendants rather than as a sword against them.

Olivia Stovicek edited and contributed research and writing.

Good piece. One nitpick re: “Some scholars also argue that the opposite is true, that a weakened public defender system makes mass incarceration worse.)” In this sentence, opposite should be replaced with converse. Even colloquially, I don’t think opposite is close enough to the meaning you are trying to express here.

Also, I think it would have been helpful to briefly explain the dynamics of the ACLU suing public defender’s offices, since both parties are fairly progressive in their missions and public defender’s offices have little influence over the larger problem of inadequate funding. Content examples:

https://www.themarshallproject.org/2016/01/28/why-getting-sued-could-be-the-best-thing-to-happen-to-new-orleans-public-defenders#.EcscoFBzi

http://www.csmonitor.com/USA/Justice/2016/0121/Why-embattled-public-defenders-welcome-lawsuits-against-them

http://www.motherjones.com/politics/2016/03/new-orleans-public-defenders-financial-crisis