Last Saturday, over 700 people flocked to Kenwood Academy for a curriculum fair featuring presentations, workshops, and a panel regarding community organizing and social justice in Chicago area schools. This was the fourteenth annual fair from Teachers for Social Justice (TSJ), an organization of educators from both private and public schools, pre-K to university, who are interested in teaching social justice concepts in their classrooms. According to TSJ co-founder Rico Gutstein, the fair is one of Chicago’s largest educator gatherings of the year.

Keynote speaker Dr. Monique Redeaux-Smith, a member of TSJ and teacher at Morrill Elementary in Chicago Lawn, opened the event with an impassioned speech on the impact that students of color could and have had on the future of Chicago schools.

“You see, these young independent thinkers might gather en masse in the streets of downtown, they might walk out of their classrooms, to protest budget cuts to their education,” Redeaux-Smith said. “They might charge genocide and fearlessly hold the police accountable for the brutality that they exact upon black and brown people.”

A panel discussion soon followed, which reflected on this past summer’s Dyett hunger strike and its implications for future activism. The panel included three members of the Coalition to Revitalize Dyett: Jeanette Taylor-Ramann, chairperson of the Mollison Elementary local school council, and Jitu Brown of the Kenwood Oakland Community Organization, who were both hunger strikers, as well as Pauline Lipman, a professor of education policy at UIC and director of the Collaborative for Equity and Justice in Education.

The discussion focused on the perceptions of the hunger strike as well as efforts to campaign for an elected representative school board, a cause taken up by many of the education organizations represented at the fair. The talk was both impassioned and introspective, with references to the myriad ways that Chicago educators and students have attempted to keep their causes in the public eye.

“We don’t wage struggle together. We go to each other’s rally, and we get a little bit of victory, and that little victory, we manufacture it like it was some major victory, and we keep it moving. Is that too candid?” Brown asked, stealing a glance at Lipman to his left, who nodded vigorously as the audience broke out in a collective chuckle. “Okay, but that’s the truth!”

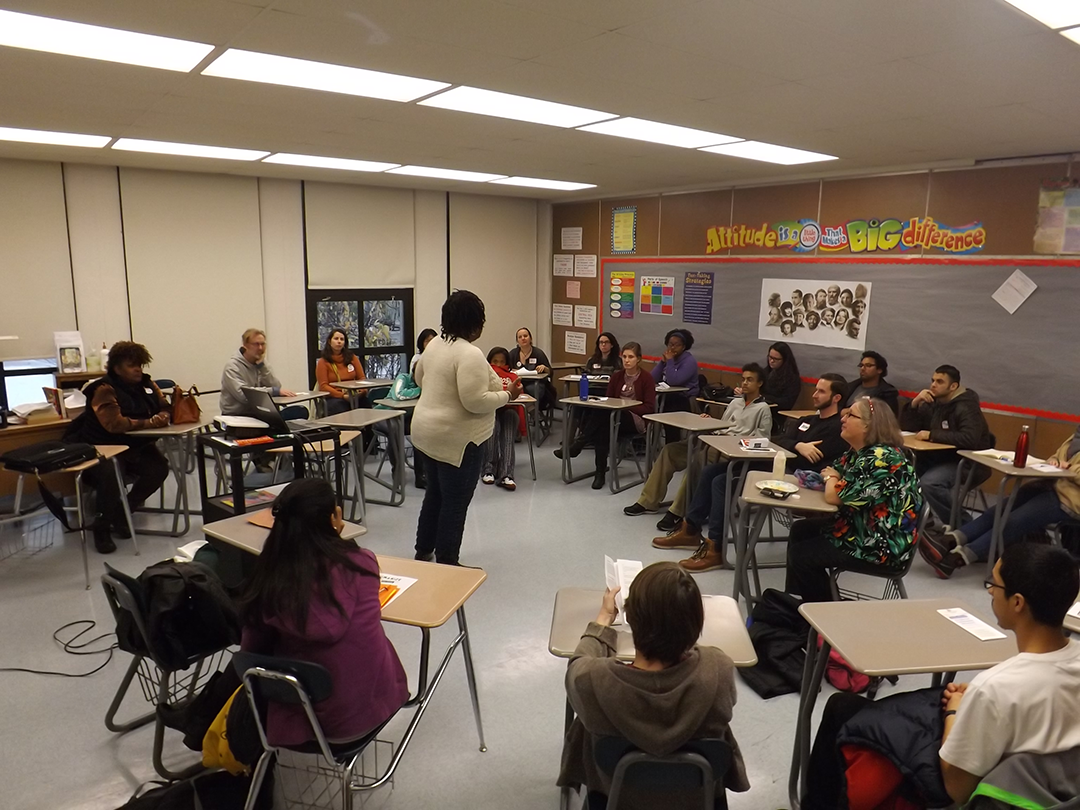

After the discussion, the crowds flowed out of the auditorium to look at the curriculum and resource tables in the classrooms and on the main floors. The classrooms housed sixteen workshops spread over two sessions, where fair-goers could learn more about social justice as it pertained to specific subject areas. “Lynching and the New Jim Crow” connected a high school U.S. history lesson with modern-day mass incarceration; another session discussed whether sexual education should be taught within a health or a social studies course. In the workshop “Students and Teachers: Unite and Fight,” Lindblom Math and Science Academy teacher Ed Hershey and student organizer Matthew Mata explored recent student-led protests across the city, including the numerous student walk-outs at Roosevelt and Kelly high schools over teacher layoffs and charter school expansion.

On the main floor, curriculum tables spanned across all subjects and grade levels. TSJ members reviewed applications for presentations from educators and organizations prior to the event, judging them on their observance of TSJ principles. These principles include the promotion of multicultural, antiracist, and pro-justice ideas as well as the utilization of multiple forms of assessment for students. According to Rico Gutstein, most applications are accepted, but he noted that some are turned away “if they seem too corporate.”

One curriculum table focused on efforts towards news literacy. The featured program began as a set of curricula for college students at Stony Brook University in New York; it’s now being adapted for high school students at alternative schools throughout Chicago, with funding from the McCormick Foundation’s Why News Matters initiative. This program, a collaborative effort between multiple groups, seeks to teach high school students how news stories are constructed, and how to discern well-researched articles from poor ones. One activity asks students to track the sources in an article from a popular media outlet like Fox News and find out if the writer quoted those sources accurately.

“That was one lesson in particular that the teachers said that students liked because they liked catching the news media outlet doing less vigorous source-checking than they should,” said Michael Hannon, program director for the Alternative Schools Network and one of the project’s organizers.

Photojournalist Riza Falk of the Erie Neighborhood House oversaw the curricula planning for this project and hired recent high school graduates to create lesson plans that would be interesting to high school students. Two of those interns, now nursing students, are workshopping the curricula with adult ESL students in Little Village.

The curricula produced by this team have also been presented to teachers through the Alternative Schools Network, where individual educators are encouraged to modify the lesson plans to fit their own classrooms.

“For me it was important because I know that education, like all things, can be very local. And by that I mean, teachers know their student population,” said Hannon. “Those schools are really working with a slightly older population of students than a public high school, and kids that already have had trouble remaining at school or that have been pushed out of school. So these teachers know these kids better than the expert, someone who is external.”

The TSJ fair doesn’t only attract teachers, but also activists and the parents of students who attend Chicago schools. Joy Clendenning, a parent, former teacher, and Hyde Park resident, ran two resource tables at last weekend’s fair. She’s a member of a number of education organizations, including Raise Your Hand, an education activism organization for Illinois public schools, and the Hyde Park-Kenwood Community Conference, of which she is the education chair.

According to Clendenning, single issues, like the campaign for the elected representative school board, or the choice for parents to opt their children out of standardized testing, are sources of common concern that connect unrepresented communities with organizations like Raise Your Hand.

“With the opt-out stuff, Raise Your Hand started getting requests to come out to a PTA meeting to such-and-such school on the Southeast Side of Chicago. That was great because we got to know these parents down there,” Clendenning said. “And when we were getting people to go talk to the legislature about getting some legislative support, we had some parents from the Southeast Side who were interested.”

The fair enables this sort of interconnectedness: it is a place where student teachers can gain insights from seasoned ones, and where parents like Clendenning can also find out what teachers in their communities are doing to make their classrooms more engaging.

“I guess I see that part of the curriculum fair that way,” Clendenning said. “That this is a place for people to have conversations [who are] generally way too busy and overworked to kind of take a step back and have those conversations.”