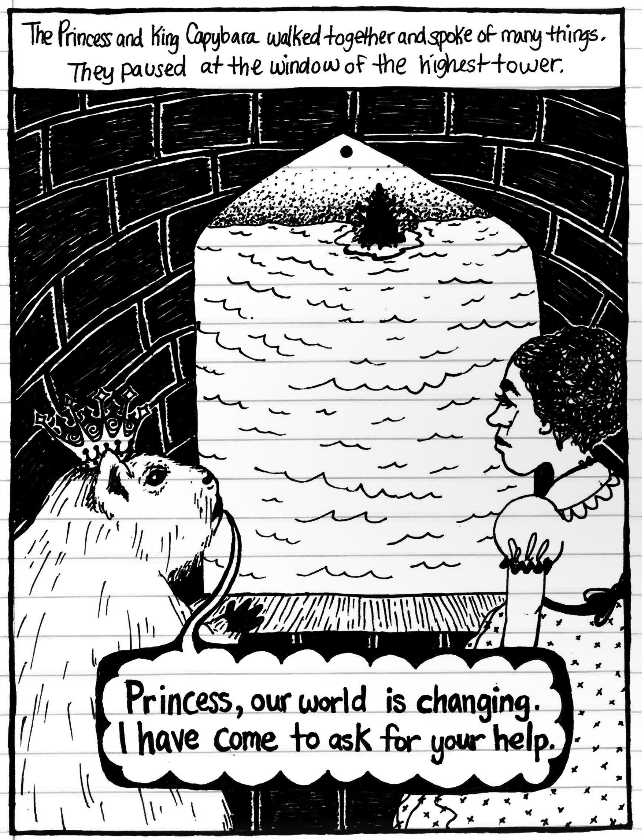

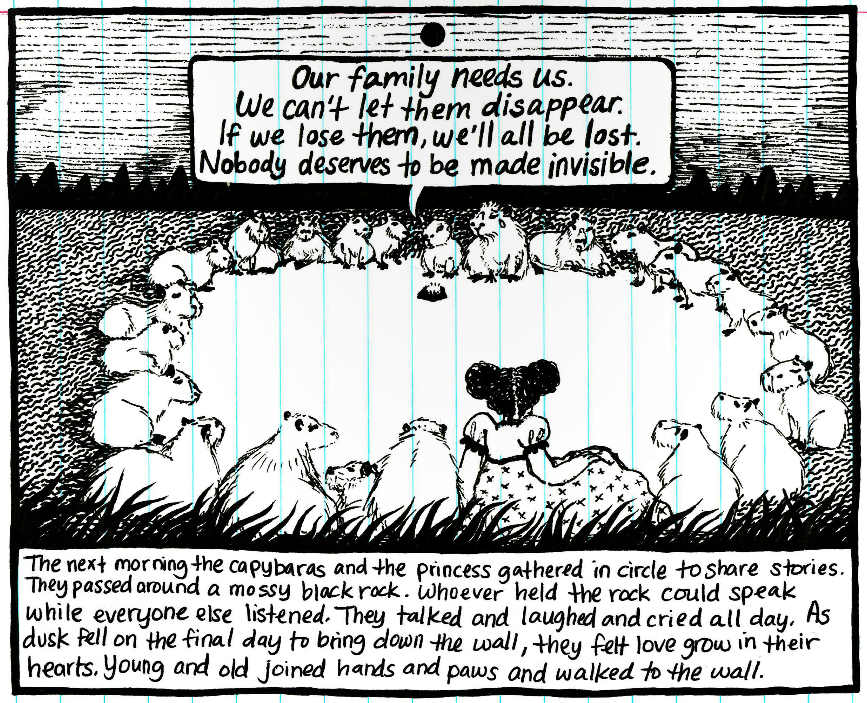

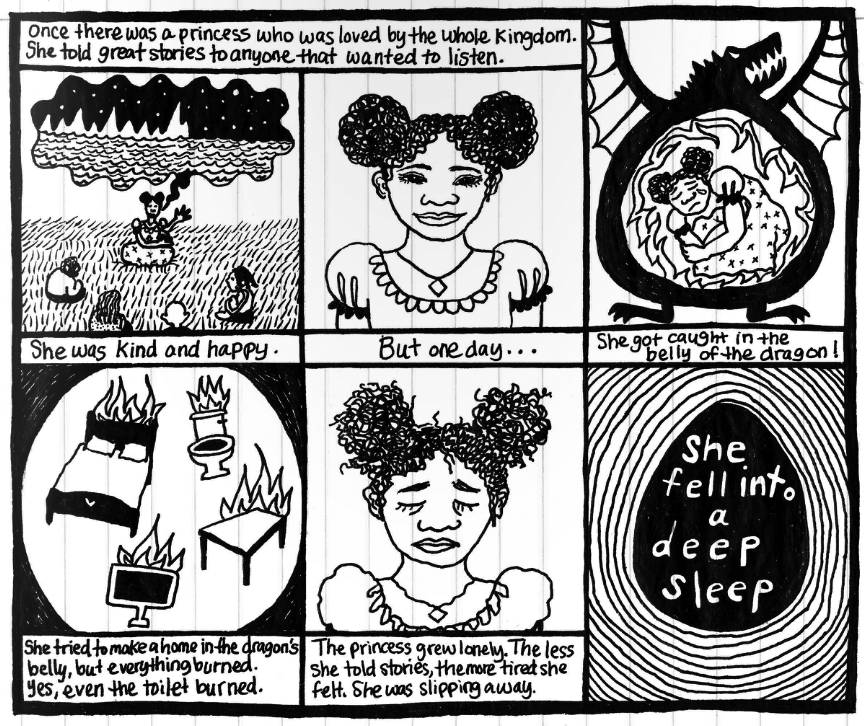

“Words spread through her lungs like vines, and blossomed from her mouth like flowers,” writes Bianca Diaz in her beautifully illustrated children’s book, The Princess Who Went Quiet. Words and stories—with their ability to transform, to illuminate, and to empower—are a central theme of this short tale about a princess who falls asleep while trapped within a dragon’s belly, but who later learns about the power of stories to strengthen family ties and escape invisibility. “This world needs you to tell your stories. They need to learn how to speak and find each other,” Diaz continues in her book. With her story, Diaz seeks to help children and parents understand how to speak openly about a very different type of enclosure—not within a dragon’s belly, but within prison walls. Through her comic-style-black and white illustrations- Diaz shows how prison is not a self-contained box which one can leave and enter as if it were just another walled room. Rather, it is like a void, where individuals become invisible behind walls—isolated from life, and sometimes families, on the outside—and often remain invisible once they leave.

Diaz’s book was distributed at an event on Tuesday in the Grace Episcopal Church in the South Loop, organized by a number of activist groups seeking to find more effective solutions to reducing youth crime than arrest, detention and incarceration. But the dialogue extended far past The Princess Who Went Quiet. The groups in attendance included Project NIA, Moms United Against Violence and Incarceration, and 96 ACRES. Before the distribution of the book a panel of brave women shared their own experiences related to incarceration and its effect on their families, discussing the importance of speaking openly about prison with children in order to diminish the tendency toward feelings of shame and ostracism.

“How do you tell your child you are going away for the second, third, fourth time?” asked Colette Payne, who is an advocate for women through the CLAIM Program of Cabrini Green Legal Aid. Finding the right words to tell your children that you must leave them for another stretch of time seems almost impossible, and many women lack the support and resources to have their children cared for while they’re away. Children grow up confused and scared, Payne explained, wondering why their parents left and whether they were to blame for their departure.

Another speaker, Josephine, has been out of prison for twenty-eight years, but the effects of her confinement have stayed with her. At the time of her incarceration, she placed her daughter under the care of relatives, unknowingly entering a decade of legal battles to reclaim her right to care for her own child. She urges more education and support for women, so that they are fully informed about child-care laws and the options they leave. When women are released from prison, struggles might include the loss of housing, the difficulty of locating secure employment, and estrangement from their children. Another woman on the panel explained that after her initial sentence, she asked her brother to tell her children that she had “gone away to college,” and pleaded with him not to bring her children to see her because of her feelings of shame. “I didn’t want them to see me here, inside this glass box, and terrify them even more.”

All five women on the panel agreed that all of us need to start speaking differently about prison, conversing openly with our children, friends, colleagues, and politicians—to them, this is the only way to combat the culture of shame that surrounds prison.

“As a society, we still aren’t properly articulating what prison is and why it exists,” says the founder of Project NIA, Miriame Kaba. “The questions we should be asking are: why are certain people always in prison? We need to include systemic oppression as part of the discussion, and we need to move away from placing blame on the individual action, but instead start talking about the system which only punishes certain people for performing this action.”

After an internship with Project NIA, Diaz started to think more about the ways to empower youth by speaking openly about prisons, encouraging community members to share their stories. The Princess Who Went Quiet is the product of her work with incarcerated youth and parents, and it is meant to encourage families and communities to connect by sharing their own stories about incarceration. “Nobody deserves to be made invisible,” Diaz writes. Open words, acceptance, and shared stories can ensure that these individuals are not forgotten.

Bianca Diaz, The Princess Who Went Quiet. 19 pages. biancadiaz.com

Congratulations to Bianca for publishing this amazing book that relates to a challenging topic.

SO proud of our former student!

Sheri Spielman

Marwen Board Member

Congratulations on this cool post.

Bob Buchsbaum,

Marwen Board Member